Rhik Samadder tries … mindful painting: ‘It dawns on me that I’m a very talented artist’

Have you ever forgotten to buy a loved one a birthday present? Here’s a tip. Get a card, then draw a picture inside of you giving them the gift you intend to buy them later. It’s a charming IOU, impossible to resent. I’m not the best at hands or faces, so the result often resembles demons in hell, spearing each other, which isn’t what everyone wants to see on their birthday. Particularly when you later forget to buy the present. To rescue an otherwise flawless system, I’ve come to an alfresco painting class to hone my dark art.

MasterPeace Studios promises to unlock anyone’s inner creativity. To prove it, those in charge tell me to choose a personal photograph I’d like to paint. I select a photo of my friend Amish Tom, at a recent pizza party we threw. In the picture, he’s rolling dough with his elegant fingers, sunlight striking his face. He’s extremely photogenic, which I don’t mind. But is he painting-genic? Why is there no word for this?

Zena El Farra, my instructor, plugs my phone into a light box, projecting the photo on to a canvas. It’s a nifty tool, letting me lightly trace an initial outline in pencil. Next, she shows me how to prime the canvas, meaning wash it with colour, using a cellulose sponge. (A plain white background is why many amateur paintings have a childish look.) I want to make vivid, unforgettable art, so taint my piece yolk-yellow. There are 15 other beginners in the sunny central London courtyard, sipping cocktails, chatting quietly. I doubt their work will be vivid enough, but they appear to be living proof that painting is good for mental health. (This is an idea founder El Farra rigorously tested, leaving a job in finance to focus on the company six months before lockdown hit, pivoting to paint-at-home kits when everything closed down.) I look at my work. The wash has blurred my tracing, and I’ve already lost the hands. For smudge sake.

As for me, I don’t believe alcohol and paint mix, unless you’re cleaning brushes. I start by sketching a pair of emergency hands. They’re pretty good. I show my tablemates, Philly and Mike, who agree, before returning to their canvases. I later learn they both have large followings on Instagram where they sell their art, so could be described as ringers. But I don’t mind. I decide to have a drink after all.

All materials are provided. Five instructors float around, offering guidance. Mixing acrylics on my palette, I point up the scarlet of the pasta sauce, the ocean green of Tom’s eyes. It’s hard to capture his alabaster skin. How do you make white? I ask. El Farra looks confused and asks me to repeat myself. “You’re really challenging the idea that there are no bad questions,” she replies. It’s true I’m growing in confidence. What does she make of my Kahlo-esque effort? “It’s fine,” she says, meaning fine art. Does she understand what she’s stumbled upon? It begins to dawn on me that I’m a very, very talented painter.

I go back to the original picture, checking the mimesis. Height, apron folds, long limbs, cheekbones, wholesomeness. The white face paint does look a little anaemic, so I splash on more tomato sauce. It’s the best feeling, to be among others concentrating, expressing their deepest selves. Opposite, Mike is drawing a closeup eye with a delicate, kaleidoscopic gradation of colours in the iris. Some would say it’s classically beautiful, but it’s only an eye. I’m doing a whole body.

El Farra stipples a giraffe, using a brush to fleck sprays of colour. The technique adds spontaneity, vivid feeling, movement. I’m having some of that. I whip my brush at the portrait with vim, Philly ducking for cover. “Things are usually more Zen than this!” says El Farra. My stipple doesn’t look like hers – the effect is necessarily unique – but it’s perfect. Others gather round, to take in what I’ve made. El Farra is speechless, perhaps understanding the student has surpassed the master. She should take all credit – my personal creativity does feel unlocked.

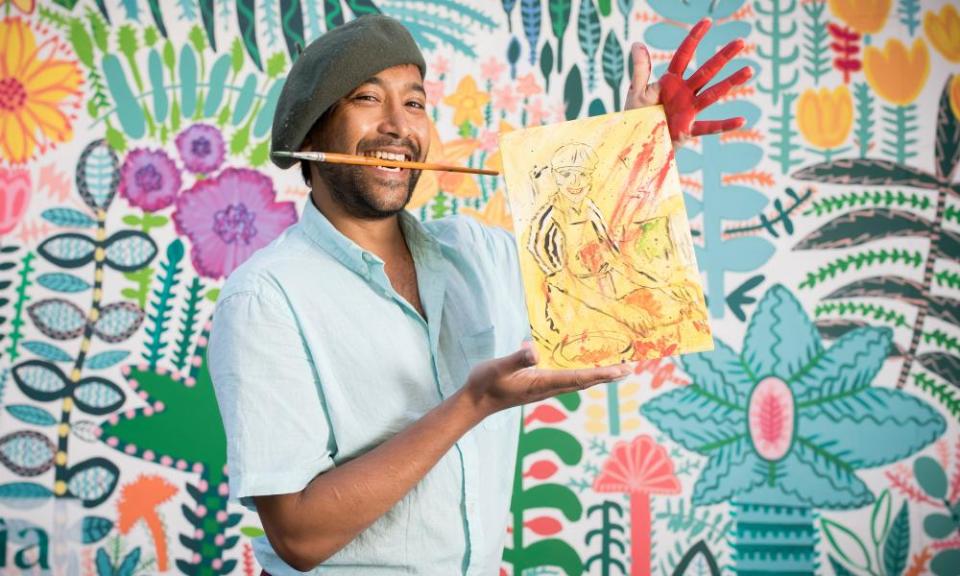

“You may as well smear a red hand down the whole thing,” El Farra advises, laughing oddly. I see what she’s driving at – pizza-making is messy, all about hands, as is painting. It’s a visual joke. I dip my whole hand in paint, a luxurious feeling, and slalom my fingers down the grain. The effect is vivid. “This is what I changed careers for,” she finally says, quietly. It’s nice to give her that moment.

A week later, in a yurt on the Isle of Wight, I present Amish Tom with his portrait, to commemorate our pizza party and our friendship. He makes a noise I’ve never heard before. Happy birthday, I say, because – twist! – that’s what day it is. There’s no need to buy him a card. Now that I’m a master painter, he’ll never go without a present again.

Who is this for?

“In lockdown, I caught myself vacuuming the ceiling. Something needed to change.” Stir-crazy Philly speaks for us all. Who doesn’t need this?

Smugness points

High. I would definitely Gauguin. 4/5

Want to suggest an activity for Rhik to try? Tell us about it here