Ryan Calais Cameron: “I wrote For Black Boys out of my pain, and the pain of people who look like me”

Ryan Calais Cameron was eating lunch in a Chinese restaurant last month when he found out that his play had been nominated for an Olivier award. “I was like, ‘No!’ in the middle of the restaurant. Everyone was looking at me and I was like, ‘Oliviers! Oliviers!’ They didn’t know what I was talking about.”

For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy was shaping up to be one of the hottest tickets in the West End even before it was nominated for Best Play for its run at the Royal Court Theatre last year. “Now,” the writer told his cast, who had broken rehearsals to celebrate the news, “there’s a premium on the show. Back to work…”

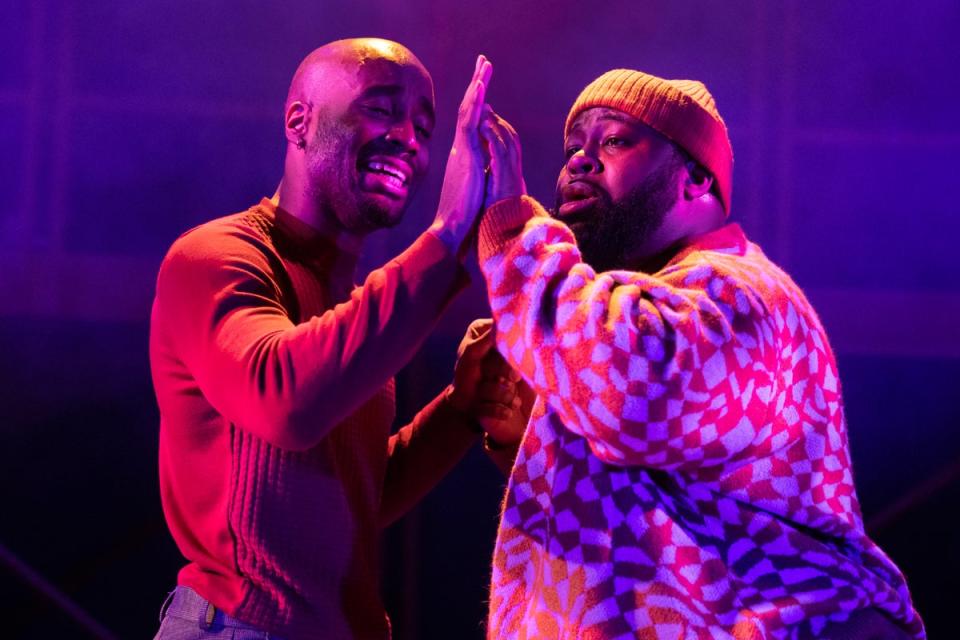

For Black Boys features six young black men who meet in a group therapy session. Over the course of the play, they discuss and argue about the numerous familial and societal problems they face. It is beautifully written – poetic yet conversational – and as well as exploring dark issues, it’s uplifting and joyous at times.

When we meet in a performance space on Commercial Road, east London, Calais Cameron tells me the play has been with him for more than a decade, from the start of his career as an actor, to becoming a playwright and now a screenwriter. And, like Calais Cameron, it has its roots in Catford, south-east London, where he grew up, the eldest of six.

“To me it was more than an area, it was a culture, a community. So, I have a particular connection to a certain walk of life: lower, disenfranchised working-class people,” he says. After returning from university, he could take a “bird’s-eye view” on the area and realised there were huge mental health issues he hadn’t considered before.

“You just think, ‘Oh that guy’s a little bit loopy.’ Actually, this person is going through psychosis, he’s going through depression, or is going through anxiety. I was able to see it more from leaving my neighbourhood. I always had this connection that I want to do something about the young men there and I didn’t know how.”

He had wanted to work in theatre from a young age, something he told the school’s career advisers when he was just 13. “They said, ‘That’s really nice but here’s information on plumbing, and here’s electrical installation because you need to know people in those industries.’” So he picked up the leaflet on electrical installation and focused on that for five years.

But it was always in the back of his mind. Aged 17, in the middle of an electrical engineering workshop, he just walked out. “I was like, ‘I’m not happy and I’ve seen so many people in my life, coming from the community that I come from, where it’s always just about get a job, get a trade, put the money in.’ Everyone was unhappy though. It was all, ‘Hate Mondays love Fridays’ – they just got on with their life and died. I was just like, ‘Why can’t I make money and be happy?’ I thought, ‘I’m just going to take this chance now – I’ve got nothing to lose.’”

He studied acting at Arts University Bournemouth, graduating in 2011. Having no contacts, he wrote to all the most prominent black actors he could think of. One, Jimmy Akinbola, invited him to a monologue competition. He was down to his last £30, but took a bus to London and wrote a monologue on the journey. He won.

Yet, he was still worried he would have to give up on his dream of acting. Then he got a phone call. Director Clint Dyer, now deputy artistic director of the National Theatre, had been in the audience for the monologue slam. He was directing a play called The Westbridge at the Royal Court and was looking for a lead. After five auditions, Calais Cameron was cast.

“Stepping out on that stage for the first time felt incredible, man, it put everything into perspective,” he says, before laughing. “Going from my last £30 to the Royal Court… We were on £450 a week and I thought I was a millionaire. I was out every night!” Also in the cast was Shavani Seth; they would go on to marry in 2018.

Now with an agent, he landed a series of parts on stage and screen, including in Casualty, Jekyll and Hyde and Luther – “working with Idris, a massive icon, was all great” – but something wasn’t right. “I was working constantly so I didn’t want to complain.” But he became sick of the clichéd characters and increasingly felt writing was where it was at – “It allowed me to create whole worlds and feel fulfilled as an artist.” He hasn’t acted since he started writing.

He wrote his first play, Timbuktu, in 2015, and it was later staged at Theatre Royal Stratford East. He then set up theatre company Nouveau Riche and his work included co-writing Queens of Sheba, a hit at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2018, and then Typical the following year.

Typical was born out of “rage” he says, when he was pulled over by the police in front of his family. “They had no grounds, and I was like, ‘I don’t feel safe to get out of the vehicle.’” He was annoyed when his wife went to speak to the officers, and later challenged her. “I said, ‘Why did you get out?’ And she said, ‘Because I was scared for your life.’ I think that was the moment my heart broke.”

He got home, started writing at 9pm and the first draft of Typical was finished at 10am the following morning. It was about the British-Nigerian former soldier Christopher Alder, who died in police custody in 1998. Starring Richard Blackwood, it made a splash at the Edinburgh Fringe and then Soho Theatre.

“It was an idea I had that wasn’t put together,” Calais Cameron says. “That night – it was a fever dream. I thought, ‘If I don’t write this now, what’s the alternative? I’m going to go and burn the whole world down.’”

But still the idea for For Black Boys was taking shape. From the mental health of those growing up in Catford, to the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012, after which he heard a conversation on the tube with someone saying “But Trayvon was a black boy in a hood”. Calais Cameron says “I was like, ‘What does that even mean? I’m a black boy in a hood. So I thought what does it mean to be a black boy in a hood, and what do we as young black men think of ourselves.” What are the structures that society and community put young black men in, he asked himself.

Another inspiration (made clear by the title) was reading For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When The Rainbow is Enuf, written in 1975 by US playwright and poet Ntozake Shange. “It changed my perspective on how to create art,” he says. “She wrote that out of pain. I’m not going to be Ntozake, but maybe I can write a piece out of the pain I’ve been through, and the pain of people who look like me.”

Growing up himself (he now has four kids), it was the pandemic that finally prompted him to write the show. “I could see the mental health of people was really deteriorating.” People in his old neighbourhood were getting sectioned or just abandoned.

“So many young men were going through things but didn’t know how to articulate them. I understood where they were coming from because I had gone through that. I was like, ‘This is it now. This is the time when this play needs to happen, and I wrote three monologues during the pandemic.”

He had set up Nouveau Riche to offer different, nuanced black characters – “I just wanted to see people who are from where I’m from. Where are the love stories? The nerds? The guys who were never in gangs?” – and this play offers conflicting, nuanced, fascinatingly different views.

“Imagine if the whole estate was just drug dealers, it would be ridiculous, man, you’d have to get the army in every day,” he says. “But if you look at the media out there, you’d go that’s what it is. I want to see different perspectives... I want us to be whole, to be fully human. I feel that young black boys, more than anything, needed to see that they were allowed to be many things.”

The play first opened in the 80-seat New Diorama Theatre in 2021 , then transferred to the Royal Court. That was a time of great vindication professionally, but personally he says it was one of the “most difficult times in his life”. The play was so personal and many people would come up to him afterwards with their stories looking for help and answers, and he felt he had to protect his mental health.

“The discussion of mental health and therapy is still such a taboo in black disenfranchised communities, it was almost like they were looking to me for answers to the issues happening in their lives.” This time around, he and the cast and crew have had some training to deal with this.

As if opening in the West End wasn’t enough, Calais Cameron’s play Retrograde, about the actor Sidney Poitier, opens at the Kiln in April. “We get to see Sidney before he becomes Sidney Poitier. We get to see someone in their innocence and purity and what shaped him, and by the end of this story, I think it will give us more understanding of how he went on this trajectory.” As for running two shows at the same time? “It’s pretty exhausting, man,” he smiles.

He is working on several TV programmes, including the Channel 4 adaptation of the bestselling book Queenie, with its author Candice Carty-Williams, who had seen For Black Boys… at the Royal Court and called him up. He is also working on adapting Street Boys by Tim Pritchard – “the first book I ever read from front to back” – and a series with Ashley Walters, set in 1970s Notting Hill. “I’m working a lot,” he says. “And as an artist, I can’t complain.”

For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy is at the Apollo from March 31 to May 7, buy tickets here; Retrograde runs at the Kiln Theatre from April 20 to May 27, buy tickets here