How Santa Claus: The Movie nearly killed Dudley Moore’s career

It gets earlier every year. That’s what the grinches say in November – as soon as supermarkets stick up their decorations and whack on Slade. Back in the early 1980s, the hype for Santa Claus – well, Santa Claus: The Movie, starring Dudley Moore as a wayward elf – began more than three years early.

In the summer of 1982, father-son producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind – also the producers of the Superman films – placed a six-page ad in Variety announcing their soon-to-be-made Santa blockbuster. Ilya Salkind claimed that it might be “the most expensive picture ever made” and that scenes would be filmed in “virtually every capital in the world”. Fifteen propeller-powered planes flew a Santa Claus banner over the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, while US newspapers reported that a herd of reindeer was flying in for the London production (also by airplane, presumably).

As promised, the film – eventually released in 1985 – was indeed expensive. It cost a massive $50 million, which was more than each of the Salkinds’ Superman films had cost. The budget, explained Ilya Salkind, was due to “the cost of getting 13 reindeer and a very fat actor up in the air”. The production also built a grandiose grotto and elf’s workshop across the 007 stage in Pinewood Studios. Dudley Moore alone – then riding off the peak of his Hollywood success as a scruffy sex symbol – cost the film $5 million.

Actor John Lithgow – who played the villain, a crooked toymaker – recalled the film in a 2020 interview with James Corden. Forget the red suit. Advertising Santa Claus as the most expensive film of all time, said Lithgow, was “a red flag”. The always-lovable Lithgow called it “the worst movie I’d ever made”. Indeed, Santa Claus: The Movie is ranked by some festive viewers as an overcooked Christmas turkey. It nosedived – flying reindeer and all – at the US box office, where it failed to recoup even half of its $50 million budget.

But it wasn’t a complete Christmas disaster. “It a very big hit in England,” says Ilya Salkind, speaking from the US. It remains a perennial favourite here – a staple of Christmas telly. Recently remastered, Santa Claus: The Movie is now back in UK cinemas and available on 4K Blu-ray.

The hype may have been big – a cinematic equivalent of a belly that wobbles like a bowlful of jelly (a line that visibly upsets the film’s body-conscious Santa) – but the Salkinds knew how to make a blockbuster. They made Superman a major movie franchise and created what is still the blueprint for superhero movies.

There’s an often-spun yarn about Santa Claus: The Movie: that when the Superman franchise plummeted with Superman III and Supergirl – both disappointments in 1983 and ‘84 respectively – the Salkinds went looking for another iconic name to spin into a multi-film franchise and landed, rather cynically, on Santa Claus. Certainly, that was part of the Salkind formula – to pick up well-established icons and put them in rollicking adventure films (The Three Musketeers and Christopher Columbus also got the Salkind treatment).

In the early 1980s, Santa Claus was perhaps the only name to give Superman a run for his money when it came to iconic do-gooder status. But according to Ilya Salkind, now 76, it wasn’t that cynical. “No, no, no,” he says, talking on the phone from California. “I just one day said let’s do a movie about Santa Claus – the most timeless legend of all time!”

As Salkind said when promoting Santa Claus, it was a decade in the making – he first had the idea for a big-budget Santa in 1975. “It was a dream I nourished for 10 years,” he said. Santa Claus: The Movie does have plenty in common with Superman though. It’s essentially an origin story about a big-hearted chap bestowed with magical powers – including the ability to fly – who does his bit for humanity. “An origin story about Santa Claus had never been done before,” Salkind told Super Site in 2010. “And I wanted to do a film that explained how he came to be as opposed to who he is.”

Ilya Salkind wasn’t the only one who believed in Santa Claus. Media Home Entertainment stumped up a reported $2.6 million – then the biggest-ever advance for home video rights.

The screenplay was written by married couple David and Leslie Newman – who also worked on the Superman movies – but Salkind came up with the story himself. He drew on various Santa legends – most obviously the gift-giving antics of St Nicholas. Salkind’s producing partner, Pierre Spengler, called their version “the true legend” of Santa Claus. Ask any ‘80s kid to tell you the story behind Santa – I’d wager they recount, in part at least, the version seen in the movie.

It stars David Huddleston as Claus, a kindly woodcutter in the Middle Ages who travels to the nearby village each yuletide to give out hand-carved toys. When Claus and his wife (Keeping Up Appearances’ Judy Cornwell) get stuck in a blizzard, they’re rescued by elves and magicked to the North Pole. The elves grant the Mr and Mrs Claus eternal life and task the newly named Santa with delivering their toys to children all over the world on Christmas Eve (all of which sounds exhausting).

There was some criticism that it was an Americanised version of Santa. In defence of the film, much of what comes to mind when we think about Santa (or Father Christmas to us Brits) – the red suit, the sleigh, the reindeer – are American inventions. But with the production set for Pinewood Studios, acting union Equity wanted a Brit to play the role and tried to block a work permit application of David Huddleston. Regardless of nationality, Huddleston was committed to the role. He piled 36lbs onto an already big-and-jolly frame and nicely sums up the film: a big, twinkly cornball.

Befriending a homeless boy, Joe (Christian Fitzpatrick), his Santa is shocked to find Joe bedding down in a doorway. “But it’s Christmas Eve! Don’t you know what that means?” asks Santa, with the same self-important condescension as Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas. Still, Huddleston is a top-ranking movie Santa, up there with Tim Allen and Billy Bob Thornton, though once you know he’s also the Big Lebowski – the wheelchair-bound millionaire who refuses to reimburse The Dude’s peed-on rug – it’s hard to not see beneath the beard and hat.

Various directors were considered for Santa Claus: Roger Donaldson (The Bounty), Robert Wise (West Side Story), Walter Hill (The Warriors), and – most incredibly – horror maestro John Carpenter, who was then in the middle of a run of that included Escape From New York, The Thing, and Big Trouble in Little China. “He would have been an interesting director,” admits Salkind. But, as the Christmas tale goes, Carpenter wanted too much creative control and to cast the delightfully menacing Brian Dennehy – then best known as the less-than-welcoming sheriff from First Blood – as Old Saint Nick. Instead, the Salkinds turned to French director Jeannot Szwarc, who also directed Supergirl for them. “Finally, we said, ‘Let’s go with the guy we know,’” recalls Salkind. “He was always on time and very, very, very reliable.” Bringing the $50 million production in on time and budget was crucial.

Another big name almost slid down the production chimney: Paul McCartney. Macca was in talks to produce a song for the film. “Sadly enough, I met Paul – I think in London – and he didn’t want to do it,” says Salkind. The film’s eventual theme, It’s Christmas (All Over the World), is sung by Sheena Easton.

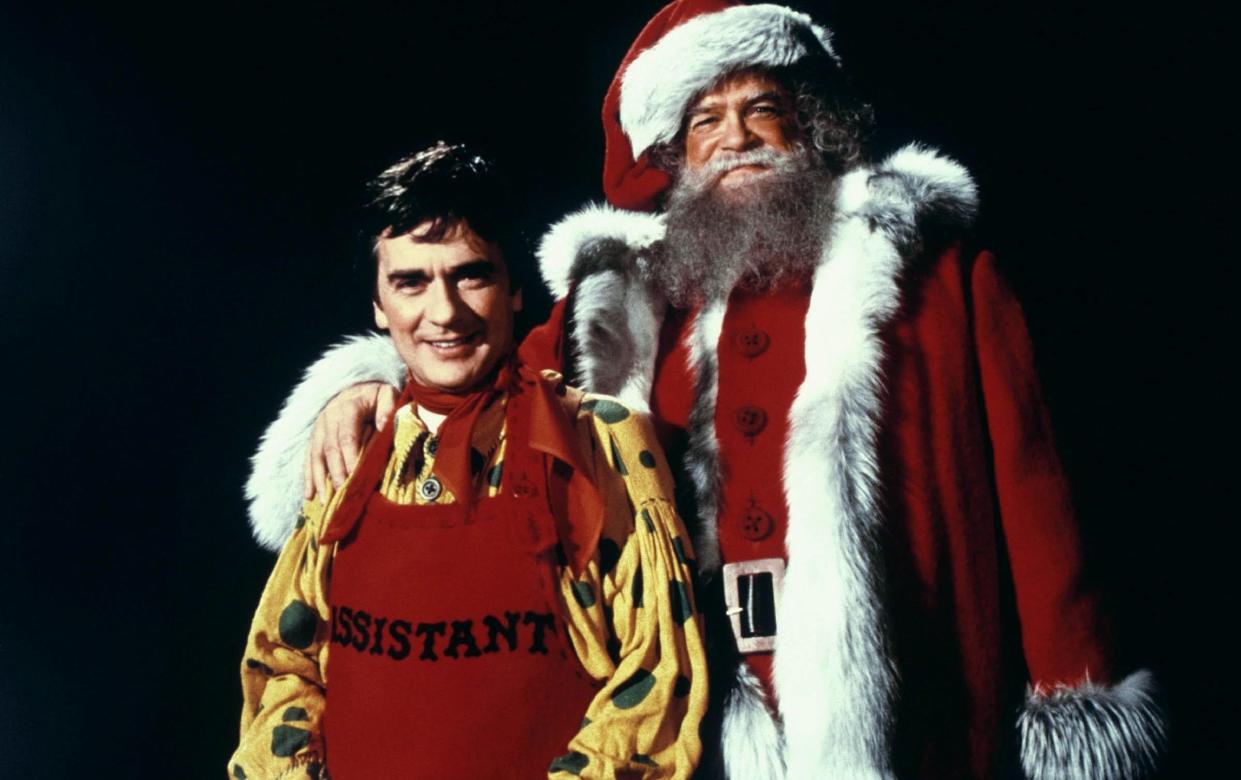

Never in doubt, however, was Dudley Moore. The role of Patch was written for him (originally called Scratch but renamed after Dudley’s son, Patrick). “He was very short,” says Salkind about the 5’2” Moore. “He was the perfect elf… He was a very nice, wonderful guy. He had a moment when he was a very big star. He cost us $5 million!”

Moore had become an unlikely sex symbol following the 1979 comedy 10 with Bo Derek – or “sex thimble” as the press called him. Moore confirmed there would be no funny business in the North Pole. “Yes, no sex,” Moore told reporters after being cast in Santa Claus. “Pity, in a way. I get kind of worked up for it instinctively these days ever since doing the movie 10.”

Moore’s film career had in fact peaked with 10 and Arthur. He was now in a run of ropey films, including Unfaithfully Yours, Lovesick, Arthur 2: On the Rocks, and Like Father Like Son. Alexander Games, author of Pete & Dud, listed Moore’s film failures and described Santa Claus: The Movie in a single word: “Doomed”.

Hundreds of supporting elves joined Moore – all men around five feet. To cast so many elf-sized men, the production had to source them from outside the acting profession. Some apparently decided to continue acting careers beyond Santa Claus: The Movie. “Ah, competition at last,” said Moore. Though when he also thought the sight of him and all the other elves together was “f–––––– ridiculous”.

According to Moore biographer Barbra Paskin, he amused other actors between takes with obscenities – like the foul-mouthed Derek and Clive he played with comedy partner Peter Cook.

The Salkinds’ speciality was squeezing two films out of one production. The Three Musketeers – starring Oliver Reed, Michael York, and Raquel Welch – was split into two films, while Superman and Superman II were meant to be shot at the same time (though it didn’t quite work out that way). Santa Claus: The Movie almost feels like two films though Salkind says there were no plans to make a Santa-verse – “The film itself ends very clearly,” he says. “I don’t think the idea was to make another Santa Claus” – though there was talk of sequels at the time.

In the first half, Santa gets his powers and gets the hang of the gift-giving lark. In the second half, Patch tries to automate Santa’s workshop with disastrous results – cue some shouldn’t-laugh-really scenes of kids’ toys falling apart on Christmas Day (“Maybe we could put out some kind of statement?” asks the head elf, dipping a curly-toed boot into the world of PR). The shamefaced Patch goes AWOL and teams up with John Lithgow’s toymaker, BZ, a corporate rotter who fills teddies with broken glass and nails. Taking advantage of Patch’s gifts (sweeties laced with flying reindeer dust), BZ plans to launch his own cash cow holiday, “Christmas 2” on March 25. It’s the movie’s sharpest idea. BZ was way ahead of the curve that eventually gave us Black Friday and Prime Day.

There is an irony to the film’s anti-corporate message and stand against the commercialisation of Christmas – undermined by the fact the film is essentially a cash-in on the Santa Claus brand, hence Santa Claus: The Movie. It’s the ultimate spin-off – the Spice World of Santa. There’s also glaring product placement. Poor homeless Joe peers through a McDonalds window – longingly coveting the Big Macs – while McDonalds sponsored some US screenings and gave away tie-in storybooks with their Happy Meals.

Salkind was moralistic about Santa Claus though. “This is not just a movie,” he told the press. “It is much more – it is the picture of my life. We hope to help bring values back with this story of a good man who just gives.” Looking back now, Salkind is still a fan. “I was very happy with the film, frankly.”

John Lithgow was less festive. “Dudley and I sat alone in a screening room at Pinewood Studios when it was all done and we watched it together,” he told James Corden. “And we sort of left the screening room shaking our heads. I do believe I remember him using the word ‘career-ender.’”

Santa Claus: The Movie was released in the US over Thanksgiving weekend 1985. “It opened well,” says Salkind, “but it didn’t continue that well. I think one of the reasons is that we should have opened earlier.” Santa Claus was ultimately pulverized by Rocky IV at the box office. It made just $23.7 million in the US.

But is Santa Claus: The Movie really a Christmas turkey? It often makes “worst Christmas movies” lists, which seems harsh when the stomach-churning likes of Love Actually and The Holiday continue to clog up ITV4 all winter. John Lithgow – despite what he thinks – is a hoot, and the scale of production is impressive (though better appreciated in the making of the documentary). And the animatronic reindeer – whose job it is to do the actual acting: mostly looking annoyed, fretful, or scared of heights – are better than anything CGI could pull out of the magic sack. (Their real reindeer co-stars were released in English parks. “If we’d sent them back to Lapland they’d have wound up as steaks,” said Salkind in 1985).

Perhaps that’s the British ‘80s kid in me talking. Santa Claus: The Movie made a respectable £5 million at the UK box office, making it the No. 7 film of 1985 and has been repeated at Christmastime ever since. Even Lithgow had to admit that it’s the source of some Christmas cheer in this country. “I have found in England, it’s a beloved seasonal favourite,” he said. “It’s your version of It’s a Wonderful Life.”

I wouldn’t go quite that far, but it’s little wonder that we enjoy Santa Claus: The Movie. It’s overblown, overpriced, tacky, and enjoyed purely for nostalgia. A bit like Christmas itself, really.