How Do You Scale a Small-Batch Fashion Brand?

Ella Wiznia didn't mean to go viral.

Last year, the founder of The Series — the locally-made, responsibly-sourced brand that upcycles found materials into whimsical, irreverent designs — had uploaded a couple videos on TikTok featuring her flower-embroidered hoods, and that's all it took. They racked up two, three million views. Then the "Drew Barrymore Show" reached out, and, all of a sudden, thousands of people were on the website, fighting over her one-of-a-kind pieces.

"Everything was sold out," she emphatically recalls.

It wasn't just TikTok. Babba Rivera was captured by street-style photographers at New York Fashion Week last season wearing the brand's black-and-white granny balaclava that served as the statement piece in an otherwise all-black outfit.

There was a staggering number of people on the brand's wait list (500 at its peak, in fact). Wiznia resorted to implementing a pre-order system — she couldn't reproduce those one-of-a-kind flower hoods crafted from thrifted yarn, but she could recreate the design with different colors. In the end, she was able to create somewhere between 40 to 80 hoods, and they sold out in minutes.

Photo: Courtesy of The Series

Photo: Courtesy of The Series

"We're not a brand that can say, 'Oh, we're ordering a thousand more — let's get one for everyone who wants them.' We didn't have that source of material at that time, so everything took a little bit longer," says Wiznia. She founded The Series in 2016 as a byproduct of her eating disorder recovery (shopping at mass retailers was a trigger), turning to thrifting and giving new life to her finds through embroidered updates.

"Of course, people dropped off the waiting list if they couldn't immediately get what they wanted. If we were a different company that was able to just knock them out, then I'm sure we would have made so much more money. But we work with women who hand-knit these, and we couldn't say, 'No sleeping!' That's not what we do."

And that's exactly what most small-batch brands contend with when they're all of a sudden thrust in the spotlight. For SVNR founder Christina Tung, who grew up making jewelry, that moment happened five years ago when she strung together a couple pieces for a few of her industry friends, who then posted them on Instagram, leading her to be hit with immense interest from editors, stylists and buyers. Presley Oldham, too, found himself in a similar situation when his first collection in May 2020 for his eponymous jewelry brand — only 12 styles — sold out almost immediately, with little-to-no paid promotion.

When you work within incredibly rigid, low-impact/low-waste parameters, when you have a business rooted in sustainability, how do you reconcile that with overwhelming demand?

Photo: Courtesy of The Series

Therein lies the biggest challenge all small-batch brands face: An inventory that comprises one-of-a-kind designs done on one-of-a-kind vintage pieces simply doesn't fit in the capitalistic mold in which the world (and the fashion industry) operates. Square peg, round hole. Factor in success and all that comes with it — garnering attention, growing a customer base, feeling the pressure to fulfill orders — and the possibility of scaling up seems mired with compromises.

"It felt contradictory…scaling up was a little trickier than a traditional jewelry brand; a bespoke situation isn't really cut out for quantity capitalism. There were moments where I was like, 'Am I silly for not taking this major opportunity? How can I take advantage of it, but do it in my own way?'" says Tung, whose first iterations of her earrings were made from pieces of a broken necklace or loose beads found at her mother’s house. "Growing up as a daughter of immigrants, I've always had that no-waste mindset; I've always had an interest in repurposing. So, the beads I don't use for a certain necklace, I can then reuse for a different design. What resonates with me is closing the loop and using raw materials already out there versus creating new pieces."

She scaled up by modifying her designs in such a way that one piece would boast all different kinds of beads, which gave her the flexibility to produce more without having to stress about sourcing the same stone.

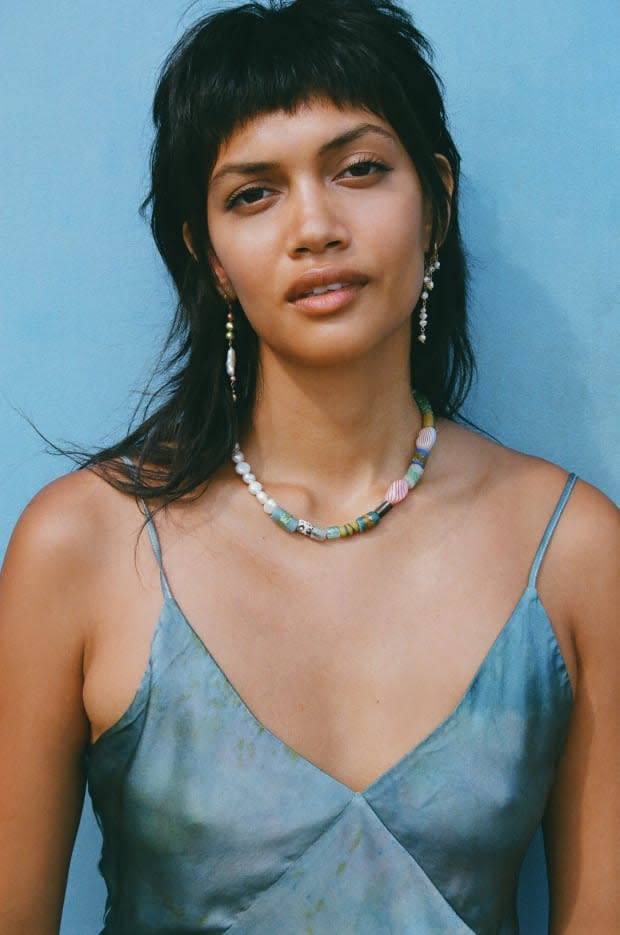

Photo: Courtesy of SVNR

Photo: Courtesy of SVNR

Wiznia worked out pyramid-like tiers of her offerings: There are her one-of-a-kind designs (the stuff with which she first launched The Series) at the very top; limited quantities of one design (a vintage crochet blanket, for example, could produce up to seven granny tanks) in the middle; and reproducibles (pieces that boast a pattern that can be reproduced through sustainably sourced yarn, like the black-and-white granny square balaclava, the Valerie cap, the Brie bag) at the bottom.

Oldham, who comes from a line of artists (his uncle is Todd Oldham, and it was his grandmother who taught him to make jewelry as a child), adopted a similar system after recognizing that jewelry pieces made from materials he previously collected from flea markets — antique Murano glass, deadstock freshwater pearls — weren't exactly viable for business.

"I realized it wasn't necessarily a sustainable business model — it was sustainable in terms of the environment, but not in terms of scaling up. There's demand, and there's also the pressure to support myself," he says."I evaluated how to not compromise my brand identity, which is handmade, thoughtful, natural jewelry that doesn't use any plastics or nonrenewable resources. I realized there can be one-of-a-kind limited pieces as a portion of the business, but there has to be a slightly larger, reproducible scale."

Photo: Myles Juzkow/Courtesy of The Real Real

In other words, it's a delicate balance between one-of-a-kinds and reproducibles; the latter supports the former. Oldham's reproducibles are intentionally sourced from suppliers he trusts: Purchasing pearls from small BIPOC-owned retailers in Sante Fe, New Mexico, for example, allows him to make 15 necklaces instead of three. And it's through this approach that he's able to ramp up his offerings and navigate wholesale by partnering with retailers (six, in fact, around the world, including By George, James Veloria and Très Bien). To avoid cannibalizing the pieces he offers on his site, he creates capsules unique to each retailer, keeping in mind their customer base, what they're looking for, competitive brands and price points.

But because Oldham does everything by hand (even with a network of freelancers to help out with wholesale orders, every piece passes through his hands), he's had to be realistic about quantities — and that's why he's had to walk away from exciting wholesale partnerships.

"It was scary," he says on turning down one potential collaboration with a notable online luxury retailer. "It's just being realistic about where I'm at and trying to set myself — and the client — up for success. I had to trust my gut on that one."

Photo: Myles Juzkow/Courtesy of The Real Real

Photo: Myles Juzkow/Courtesy of The Real Real

Wiznia has also struggled with wholesale orders, initially showing buyers pre-existing materials in their raw form (a comforter, for instance, that could potentially be transformed into a jacket). While there was interest, buyers mostly liked the idea in theory, not so much in execution. (The jacket design had a different lining, or there was more wear on the inside, or it differed slightly from the prototype, and so on.)

"The first year we started doing wholesale, I would wake up in the middle of the night, and think, 'I don't know if I can find a quilt that looks exactly like that.' It was horrible," says Wiznia, who was often plagued with nightmares of scrolling endlessly through eBay scouring for materials. "[When it comes to one-of-a-kind pieces], I now know that doesn't work in a scaled-up way. Even if it's a really exciting partnership, I can't…just for my own mental health."

Nomasei, a luxury footwear brand that holds sustainability and transparency as core tenets, avoids the stressors of wholesale altogether by being direct-to-consumer — and the founders Paule Tenaillon and Marine Braquet intend to keep it that way. A unique business partnership with a manufacturer allows them to slow down, introducing only one or two new styles per season versus full collections, and to create less waste by making orders extremely small (60 pairs, for instance, as opposed to say, 200), to prioritize quality over quantity.

"A factory usually loses money with such small quantities, because they have to learn how to make the style, so there's waste," Tenaillon explains. "Our factory, which has shares [in Nomasei], takes the time to perfect each style. They take twice the time they should."

Photo: Courtesy of Nomasei

It's for this reason that so many of Nomasei's SKUs are constantly sold out. With its most popular style — the Adora, a delicate-meets-bold sandal that's tied with a giant bow in the back — the founders admit to feeling the pressure to make more to meet consumer demands: "I think it's human to feel that way," Braquet says. "When you're an entrepreneur, you have highs and lows. Some days, you feel like nobody cares about your brand, and other days, you feel like you're the king of the world. What helps is to remember that we made Nomasei so we could take it slow, to make products that are perfect." Which is to say, if a Nomasei style is sold out, then it's sold out, and the consumer will simply just have to wait for it to come back in stock (about two, three months).

Oldham deliberately tries to sell out of each style — and once it's done, it's done. For Tung, she's able to keep her business liquid, scaling up or down as she sees fit depending on her bandwidth or her mood. Everything she does, both her hand-dyed slip dresses and her gemstone/beaded accessories, is made-to-order, which means she neither has overhead nor inventory, and therefore, doesn't need to host sales to move product. Growth is important ("If you're not growing, you're dying," Tenaillon quips), so long as it doesn't come at the expense of a core brand value or personal happiness.

Tenaillon and Braquet are hesitant to take Nomasei to the next step, because that would mean one thing: investors.

"When you take [investors'] money, you take their input as well," says Braquet, explaining most of Nomasei's growth thus far stems from word-of-mouth and an incredibly loyal fanbase. "And we’re super afraid they'll say, 'Girls, your margins aren't high enough, you need to do handbags, this factory in Italy is too expensive.'"

Photo: Courtesy of Nomasei

Photo: Courtesy of Nomasei

"The goal was never to be huge," adds Tenaillon, though she admits that they struggle with a desire to remain small and the need to stay relevant. "Social media forces us to grow more than we would like to, but the goal is to live in harmony with our values and with our passion. Nomasei is our passion. We want to create the best shoe company that combines sustainability, luxury, and timeless style…like Hermès — but less expensive."

Oldham has big plans for his brand. He just doesn't quite know what that growth means for his role yet.

"What changes when I'm not the person making every single piece? To be honest, I don't have an answer. I'm still reckoning with it," says Oldham, who dedicates about 70 hours a week to making jewelry. He most recently collaborated with The Real Real, transforming broken jewelry into 35 unique pieces using all different gemstones. "It's important to me that I'm still making small batches and one-of-a-kind pieces, but I think I'm going to have to add in a really sellable thing that I can make at a higher quantity — maybe it's a strong, simple silk necklace. Last year, I more than doubled my sales from 2021. So, I'm doing something right. I'm just trying to follow that thread and not pull too quickly."

Wiznia, too, wants to figure out a way to meet consumer demand by creating more reproducibles made sustainably from pre-existing materials, but she wants to make it clear: The Series will always have one-of-kinds, like the chore shirts and the puffers.

"We prioritize sustainability over demand, craft over commercialism. That’s always been our intention. And we cannot grow faster than we should and get tripped up along the way," she says. "All of our pieces are rooted in domestic practices that have been undervalued for so long: crochet, quilting, embroidery, and tapestry. There's a comfort in those materials, and that resonates with a lot of people." (An example of what that innovative thinking looks like: The Series recently partnered with clothing rental service Nuuly to upcycle 500 units of secondhand denim.)

But Tung has taken more of a philosophical approach to her business. She's had to take a step back and ask herself a series of questions before landing on what truly matters: her happiness.

"I've definitely thought, 'I could make a lot of money if I did something different.' But it always came back to: Am I doing this to make money or am I doing this to have an outlet for my creativity? The trick of capitalism is thinking that you need to always have more, make more money, grow X percentage year-over-year. Could I be a huge global brand? Maybe…but would that make me happier?" she muses. "I'm happy with where I am. I'm not overcommitting myself to a place where I'm unhappy or I'm overly stressed. And I think it shows in the design: These are joyful pieces that are colorful and beautiful."

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.