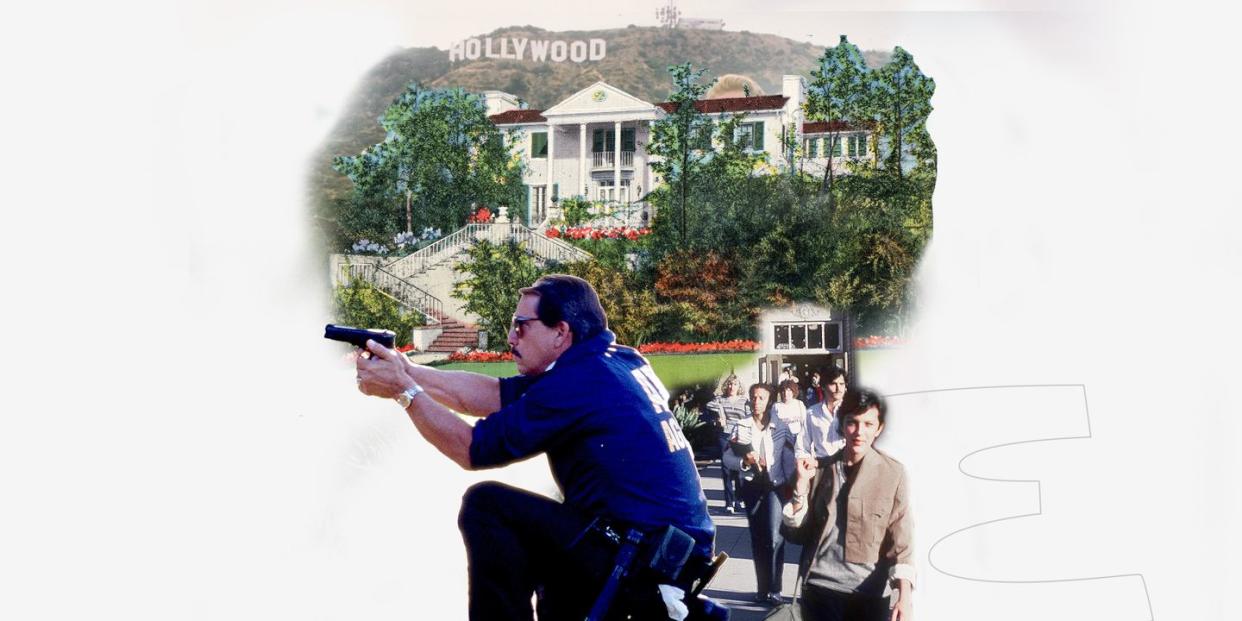

Sex, Lies, and Murder on Mulholland Drive

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

There was a distraction, a flaw in the paradisiacal canvas of the summer of 1981: the disappearance of a girl leaving a party on the outskirts of Encino in late July.

There was very little reported about the disappearance at first and none of us knew her—she might have stayed a rumor or what would later be known as an urban myth, teenage girl disappears from party never to be seen again—but she was soon connected to two other cases, one from the summer of 1980 and another in January of 1981, and after Julie Selwyn’s body was discovered at the end of September, it was revealed that the victims resembled each other and there were details about their deaths that connected them as well. In 1981 no one knew what had happened specifically to Julie Selwyn or Katherine Latchford or Sarah Johnson, or that the same person or persons had killed them—just that they had been abducted and were missing for two months with Katherine’s and Sarah’s bodies discovered in remote locations, called in by what investigators assumed was the killer in a fake groaning drawl, who wanted to know why the girls, dumped weeks earlier, hadn’t been discovered yet—he was waiting for his work to be admired. The matching mutilations that the victims suffered were not fully revealed to the press and it was almost a year after the last girl was found at the end of 1981 until most of these details were ultimately known—in a pre-digital world secrets were more easily kept; in fact, secrets were the norm in a pre-digital world. Before any confirmation was made there were only rumors concerning the specificity of the mutilations and how the girls had been tortured and killed. However, there were leaks, anonymous sources verified, containing details so obscene that if you believed them you quickly realized why the Los Angeles Police Department kept the details of what they called “the injuries” as vague as they did. Because those who knew exactly about them—had perhaps seen the wounds during the autopsy beneath the fluorescent lights in the morgue—didn’t want the populace to become overly frightened.

The public didn't know this yet but Julie Selwyn would be the third victim of a serial killer who came to be known as the Trawler— this was a nickname that two investigators in the Hollywood division of the LAPD jokingly came up with in private. It was a lewd joke that involved fishing methods, operating a net, the storage of fish, what had supposedly been done to the girl’s vaginas, the contents of Katherine Latchford’s own aquarium had been missing a week before she was abducted and found sewn into hers—though it was actually rubber cement that the killer used—which meant that Katherine Latchford had been targeted weeks before she was abducted. “The Trawler” was a dumb name—it came nowhere near defining the totality of the killer’s madness—but a memo had been leaked to the press, and in one line that hadn’t been redacted “The Trawler” was clearly referenced and became the name of this nascent serial killer in the few articles that appeared: it hit the right ominous note. But in the summer of 1981 the Trawler had not officially been named yet—the victims were just beginning to become connected and the series of articles in the Los Angeles Times confirming this wouldn’t appear until late September. No one knew yet that Julie Selwyn would be the third victim of a serial killer that had been operating in L.A. County since the summer of 1980 when Katherine Latchford disappeared mid-June. It wasn’t until the third week of our senior year that the Trawler would be named, introduced to us and emerge as a character in the city’s narrative.

When I look back at 1980 and into the fall of 1981 we didn’t think we knew anything about the Trawler yet: meaning we didn’t know his name or how he got his name, we didn’t know what his history was and we didn’t know he was about to thrive and kill three more people that autumn in L.A., one of whom we knew. But beginning in the summer of 1980 there were a number of signs, of clues, that were an actual and legitimate part of what became the Trawler’s pattern, the narrative he was building, the story he wanted to tell, that we did know about. Later on it was confirmed that there were explicit warning signs if the Trawler had actually targeted someone but in the early days no one knew any of this yet: the connections hadn’t been made.

Beginning in the late spring of 1980 a series of home invasions started announcing themselves in the hills above the San Fernando Valley. There was no pattern—young couples, old couples, a single male screenwriter, a woman who lived alone, families where there were teenage girls as well as teenage boys—and though girls ultimately became the preferred victims of the Trawler, initially boys were attacked during these home invasions as well and one boy was later killed by him. The home invasions that we knew of and read about in the spring and into the summer and early fall of 1980 seemed totally random: since no specific type was attacked—gender and age seemed irrelevant, it was girls and it was boys—there was really nowhere to hide, no way to protect yourself against this person who was committing the home invasions, everyone was vulnerable. People began to finally piece together that one of the clues connected to the Trawler (again, not named yet) had to do with animals. The Trawler focused on someone whose family had pets or the victim had a pet themselves (and it didn’t matter if it was a dog, a cat, a bird, a snake in one instance, mice, a rabbit, a guinea pig) and the pet would disappear, and not only the victim’s pet, but other pets in the neighborhood where the victim resided would vanish as well in advance of the home invasion when the victim was attacked. Before he committed his assaults often three animals, in the same neighborhood, would ultimately be sacrificed by the Trawler, and it wasn’t until the late fall of 1981 that we learned what the reason was—what he ultimately did with their carcasses and why he needed them.

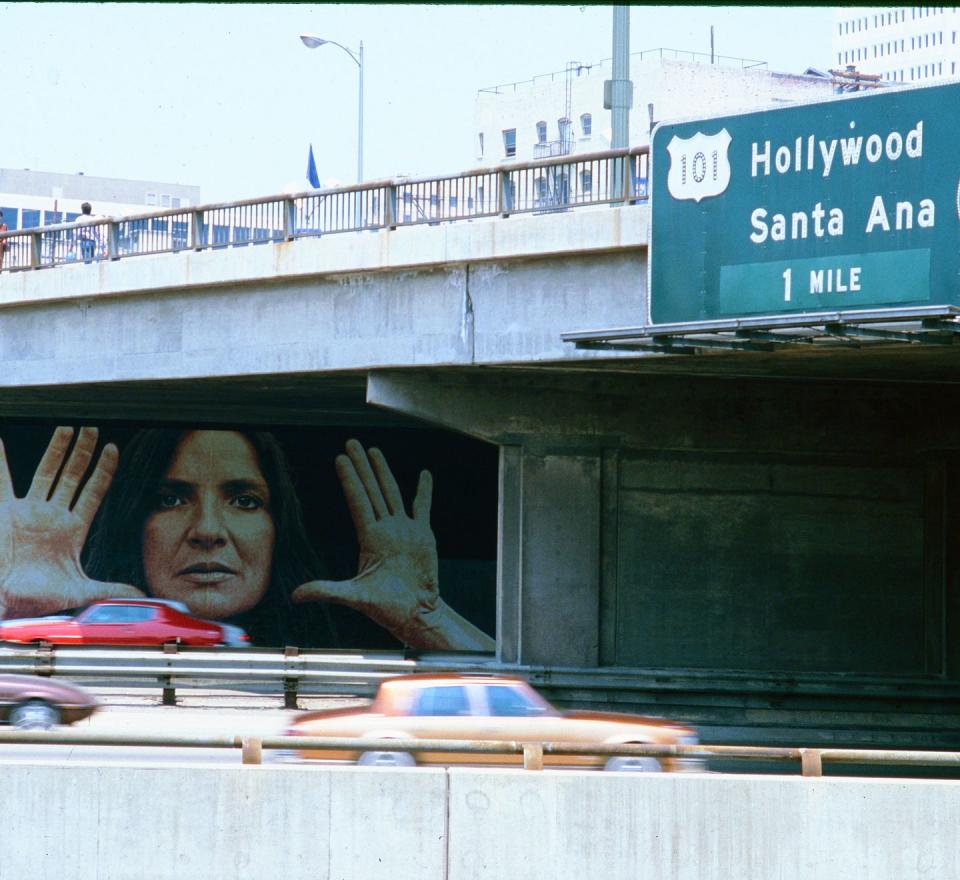

The home invasions began in May of 1980, when it seemed the Trawler was simply testing things out. The Trawler at this point didn’t enter properties and remained shrouded, his presence announced only in the clichéd language of horror movies: someone remembered hearing the wind chimes hanging over the veranda in a house on Oakfield Drive in Sherman Oaks even though there wasn’t the slightest breeze on that June night, or there was the shaky beam of a flashlight someone on Woodcliff Road reported in mid-July, held by a figure clad in black who was standing on the deck beside the pool, and in his other fist was the glint of a butcher knife. During the summer of 1980, a time when the Trawler hadn’t been named and hadn’t killed anyone yet (Katherine Latchford disappeared mid-June but her body wasn’t found until two months later), there were increasing reports of an actual intruder and the witnesses who supplied descriptions of this person were vague because of the black ski mask and the matching jeans and turtleneck he wore: he was tall, he wasn’t that tall, he was lean, he was built, he was heavy, he had “wild” and “violet” eyes, no one had seen his eyes, they were a piercing blue, they were hazel. Whoever played this character was extremely elusive—a shape-shifter— though he was responsible for twenty break-ins that summer alone in the homes on the San Fernando Valley side below Mulholland, very close to where I lived, and stretching from Studio City through Sherman Oaks and into Encino, and then briefly into Bel Air and Benedict Canyon, and then the home invasions became scattered (Pasadena, Glendale, Hollywood), and then abruptly stopped.

They didn’t start up again until mid-December where they continued throughout January of 1981. No one had any idea at the time when Katherine Latchford’s body was found in August of 1980 that she was connected to the home invasions that had plagued the city, or that it was connected to the disappearing pets and the actual assaults. Later we would find out that phone calls were often made to a targeted home where the next victim resided days before the attack, coming from phone booths lining Ventura Boulevard or Burbank or Reseda, or across the canyons on Sunset and into Hollywood, almost as if the calls confirmed something for the Trawler—the victim would pick up, ask who was there, the Trawler would say nothing, just listen as the confusion morphed into annoyance, and then fear. Later there would be other clues usually offered when one of the victims’ memory would kick back in: someone, it seemed, had entered the house previously, before the night of the attack, something about the kitchen or the contents in a bathroom or the bedroom was “different,” leading investigators to believe that the Trawler had familiarized himself with the residence in the days before the assault. Later someone noted that Katherine Latchford—the first of the murder victims, the pretty girl with feathered hair and full lips and sleepy eyes that were half closed in the yearbook photo that became famous—complained that her cat had disappeared in the days before she vanished, and unbeknownst to her two dogs from the neighborhood were missing as well. Katherine had also told her parents that she’d been receiving “strange” phone calls in the days leading up to her disappearance— they weren’t obscene but in a way they were worse because of the silence: you had no idea what the person on the other line wanted. It seemed there were limitless possibilities that your frightened mind conjured.

Ultimately, it was noted, there was something methodical and patterned about the Trawler’s attacks—they were so carefully pre-assembled that a plan was suggested, an actual narrative, something being consciously created; they weren’t random or impulsive at all. There was, in fact, an ornate staginess about them. At first it seemed that the attacks were created by someone who was ambivalent, and this was confirmed when certain victims involved in the first wave of invasions during the spring and early summer of 1980 admitted something that didn’t line up necessarily with a person who had broken into your home and assaulted you. The victims who survived these initial attacks, the ones in May and early June, before Katherine Latchford was abducted—people who had been roped and bound, prone on their bedroom and living-room floors, sometimes stripped by the figure clad in black and wearing the overlarge ski mask—said that whoever had attacked them was “weeping” when he left the residence after he had apparently been sated: a few of the attacks were sexual in nature but most were not. When the first murder happened, and the home invasions and the assaults picked up in mid-December after the long lull of a three-month hiatus, many people who survived the next wave of invasions commented that the attacker hadn’t cried at all; it was almost as if he had gained confidence, a strength, and perhaps by committing his first murder had become emboldened.

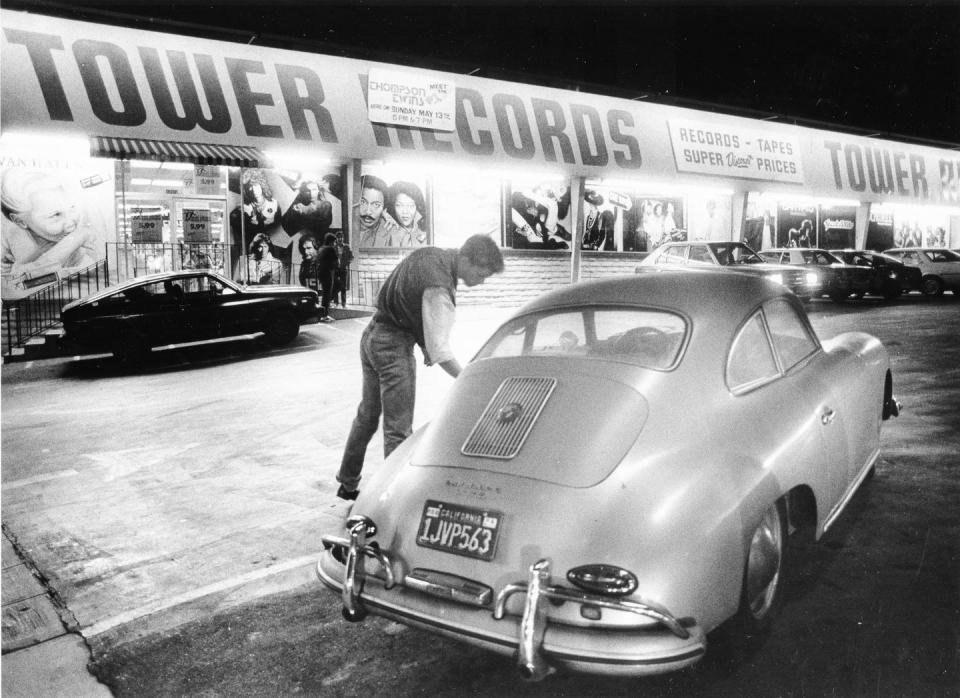

The lead-up to the Trawler’s first victim became the elaborate template: the disappearing pets, the phone calls, the rehearsal break-in—but not an assault. This was true of the second victim as well: Sarah Johnson abducted behind the Tower Records on Ventura Boulevard in Sherman Oaks in early January of 1981. Her body was discovered eight weeks later in a drainpipe at an abandoned construction site on the outskirts of Simi Valley; her cat had disappeared, she complained to her mother that the furniture in her bedroom had been rearranged, and someone was calling her, breathing into the phone, not obscene exactly, just unnerving but she was never assaulted in a home invasion. Sarah had left a party in Tarzana and drove to pick up a cassette on the way back to her parents’ home in Studio City but she never made it into the Tower Records on Ventura Boulevard and her remains wouldn’t be discovered until the first week in March, found in the same condition and with the same “injuries” as Julie Selwyn had suffered when she was found in September of 1981, rotting on a public tennis court in a park near Woodland Hills; she had been propped up and splayed against the net, her head just a skull with flesh stretched over it but with a full head of hair and empty sockets where her eyes had been gouged out, and what had been inflicted upon the rest of her body—what the hideous mutilations represented—we wouldn’t find out until the end of the year when the details were finally revealed in a long article in the Los Angeles Times, having only been previously alluded to because of the grotesque and upsetting nature of the injuries.

I had moments when I was afraid of whoever was committing the home invasions and that the house on Mulholland might be its next target but for some reason I thought my odds were okay as a lucky seventeen-year-old—there were so many things I was preoccupied with, and the home invasions never really got covered in the way they would have if everyone knew what the Trawler was ultimately capable of: they never set off a mass wave of panic. It seemed my only point of reference in the summer of 1980, when the Trawler began announcing itself, was trying to figure out Matt Kellner. What had become a mild sexual obsession with a classmate distracted me for about a year, until I realized that Ryan Vaughn was going to eclipse Matt. And on that Labor Day Monday I woke up late in the empty house on Mulholland thinking about Matt as I usually did, even though Ryan was beginning to crowd my thoughts, replacing not only Matt but also Thom Wright and Susan Reynolds in my dreams and fantasies.

My parents would be away most of the fall, traveling through Europe on a number of cruises trying to repair their flailing marriage after numerous separations and I had zero interest in the outcome—divorce was preferable to the agonies that the marriage played out, and it became increasingly apparent as I moved through my adolescence that I wasn’t particularly close to either my mother or my father. We were all distant from each other even though the public façade, the Boomer narrative, suggested otherwise: the Christmas card with the posed family photo emblazoned on it, the sleepovers I had where my mother acted like a concerned chaperone checking in on us as we watched the Z Channel, the days at the beach club with Thom and Jeff and Kyle that my father oversaw and where he acted as if he was our best friend—all of it seemed fake, performative, unreal. There was no doubt my parents loved me and if pressed I would admit I loved them back but I was becoming an autonomous adult and realized that I didn’t need them in the ways I once had.

And alone in the house on Mulholland that fall I felt even more like an adult because I had the entire place to myself, even though my bedroom—huge with a sweeping view of the San Fernando Valley— was its own self-sustaining home I almost solely resided in: I had a separate entrance with a veranda that led out to the pool, and a kitchenette with a refrigerator filled with ginger ale and Perrier, a massive bathroom with its own separate shower and tub, and my room was situated close enough to the garage so that I barely spent any time in the rest of the house. Our Nicaraguan maid, Rosa, was off Labor Day weekend and wouldn’t be back until the following Tuesday. Though my parents would be away for twelve weeks my mother wanted Rosa to stick to her schedule anyway—she confided in me when I complained and insisted I could look after myself that Rosa needed the money. Her job while my parents were gone was to basically look after the only child, the privileged son, and make sure the kitchen and my bedroom were kept clean, to wash my towels and launder my sheets, to let in the gardener and the pool boy and the landscape designer my mother had recently hired. Rosa was there to collect the mail, attend to the shopping, prepare my meals, and make sure Shingy—my mom’s dog, a Lhasa Apso–mutt mix—was washed and groomed every two weeks while my parents floated across Europe. I would be updated on their location with rambling messages left always by my mother on my answering machine.

With Rosa gone on that Labor Day it was my job to make sure Shingy was fed and let out onto the lawn adjacent to the pool in the yard, overlooking the Valley where it dropped onto a hillside lined with eucalyptus and jacaranda trees, while I idly sat in the Jacuzzi and watched the dog sniff around, keeping an eye on him because of coyotes and where I could faintly hear the occasional sound of a car passing behind the huge boxwood hedge that separated our property from Mulholland Drive. I ushered Shingy back inside, where I debated calling Ryan Vaughn but decided he would perceive this as too needy and called Matt Kellner instead, but no one picked up—he didn’t have an answering machine—and so I drove down to Encino, where Matt would be high by the pool, and I remember I didn’t masturbate that day because I was sure something would happen with Matt and so before I left I reread pages I’d typed of the novel I was working on while smoking clove cigarettes and listening to Elvis Costello until I got bored and then sped through a third of the new Stephen King, Cujo, which had just been published that August.

Matt Kellner was a tall, green-eyed Jewish guy with a killer body who was also the class stoner and I, at one point in the fall of 1980, had come to believe that he would’ve had sex with anybody, boy or girl, if they made themselves available to him in the ways that I did, but no one at Buckley seemed to have found Matt Kellner as intriguing. Part of the reason had to do with the fact that Matt was always too distant, lost in his own world, you could never reach him, he was far away from everyone, it almost seemed as if he’d been wounded by something so profound (though he never revealed what it was) that it altered the way he dealt with people. I’d been watching Matt since he arrived at Buckley in seventh grade, and though he should’ve been popular he was simply too weird—if he had just acted vaguely “normal” he could have been a star because of how physically hot he was but instead he became a kind of outcast, an increasingly fumbling and awkward dude, a parody of a privileged young Valley stoner, and no one was interested. But I grew to like him and his pothead amiability and it was also the gray Buckley slacks worn just a little too tight, overaccentuating his ass, and a noticeably visible bulge, that became so distracting to me as we got older. Matt seemed to have no capability for basic socializing, and at first I wasn’t sure if this was because of how stoned he was all the time or if he was just inherently shy, but I soon realized that he simply didn’t care about the social contract we had all bought into—he didn’t even seem aware of his surroundings—and there was something rebellious and almost punk about this stance even though it wasn’t conscious: he simply didn’t care about how things worked; in fact he seemed defiantly un-self-conscious. I noted how he would walk naked through the locker room, from the bench where he took his sweat-soaked clothes off after running track, to the showers, and back again, just naked, drying himself off completely unaware, shamelessly, and no one, not even Thom Wright or Jeff Taylor, was that easygoing with their body—everything was always slightly shy and muffled, you’d shower quickly and then walk back to your locker with a towel wrapped around your waist, and then hurriedly change into your boxers or briefs. But Matt Kellner seemed to revel in his nakedness and I secretly reveled in it, too.

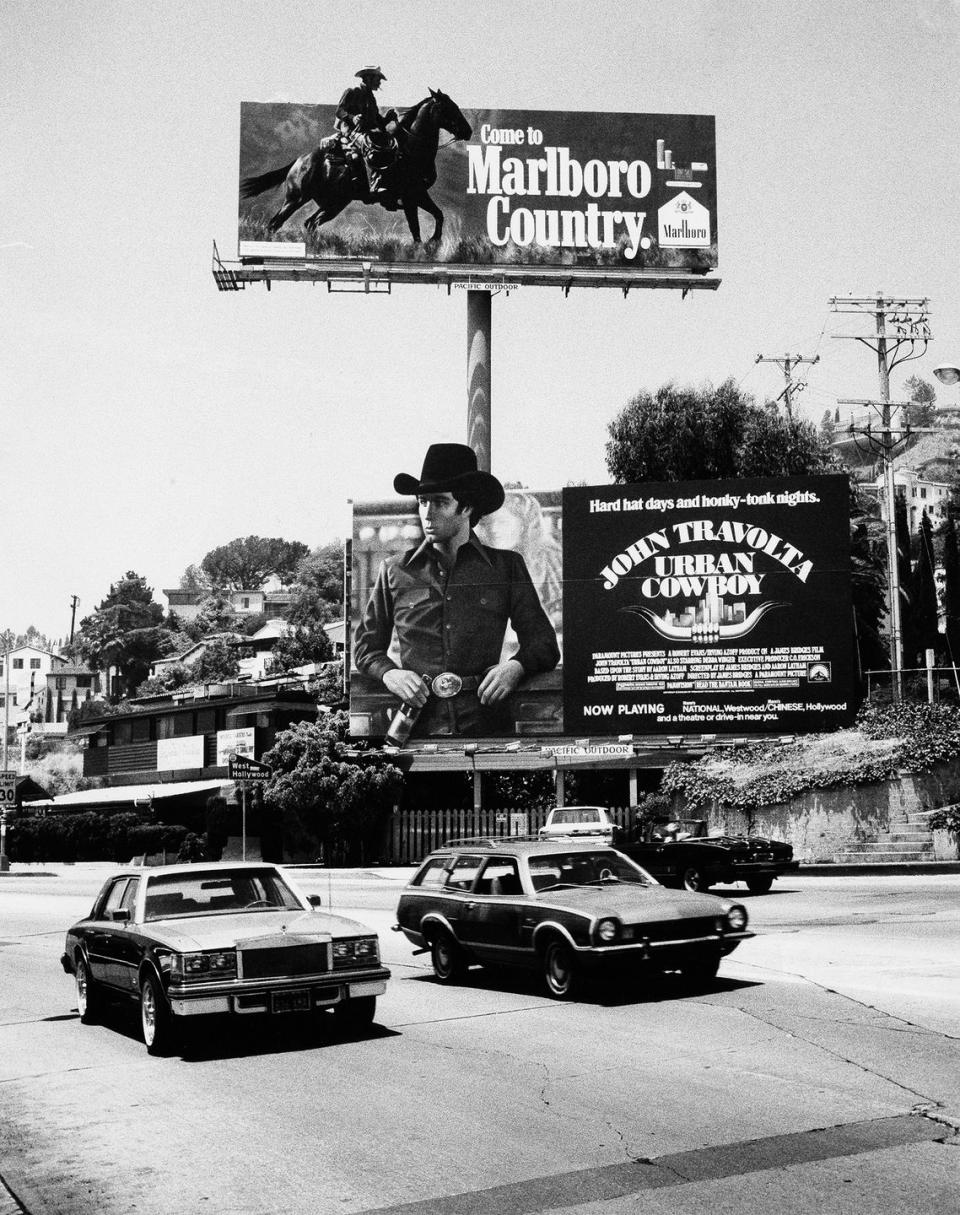

I had been going to Matt’s house on Haskell Avenue in Encino ever since a July afternoon in 1980 when we were both sixteen and two of about forty students at the Buckley summer program. I had failed Geometry and Science the previous semester, and Matt had failed them as well, and during breaks in these morning sessions we attended in order to pass those classes so we could move on to the eleventh grade, we started hesitantly talking to each other even though we never had before. Had I seen Urban Cowboy, he asked; he’d been to an advance screening of Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie on the Universal lot a week ago; was I a fan of “Funkytown” by Lipps Inc.? Matt liked that song as well as the new Queen record, The Game. And in that first week he invited me to the house on Haskell—his parents were away, we could go swimming, get high—he was so amiable and friendly that it bordered on stoner parody and I wasn’t thinking about anything else except sex when I listened to him because I instinctively knew—not that Matt seemed gay at all—there was the possibility for something sexual to happen; it might not have existed in the invitation itself but there was a suggestion about the invite that was going to let me initiate this somehow and the path to Matt’s house became familiar that summer. He lived in a pool house in the back of his parents’ palatial Encino estate, retrofitted into a kind of hip beach shack with a nautical theme: a shellacked dolphin hung from one wall, pastel surfboards were resting against another, an elaborate aquarium ran the length of the room filled with swordtails and pearl gourami and starfish and multicolored snails, and coral beds lined the bottom of the tank lit in shades of blue and green and purple. The room was complete with a stereo, a large TV that had the Z Channel connected to it, and a refrigerator stocked with 7-Up, Corona and bags of pine-green weed, and sometimes a cat—Matt had named it Alex for some obscure reason—would slink into the pool house and sprawl out in front of the aquarium, staring up at it blankly, licking its paws.

That July afternoon we got high and swam in the pool, first in bathing suits and then naked, and the moment Matt suddenly tugged his off—from where I was wading I saw he was half hard as he rested on a hammock strung between two palm trees, sunning himself—I realized what was going to happen and I hitched in a breath as I pulled my suit off and tossed it on the edge of the pool and began swimming toward Matt. I didn’t want anything from him except his full-lipped mouth surrounded by light razor stubble, his muscular thighs, the chest with defined pectorals that tapered into a tier of abs, the small line that crept up from the patch of brown pubic hair and ended at the knot of his navel, and the long cock that jutted out from that patch, and his ass, pale and tight and dimpled, very lightly dusted with blond down. At first it hardly mattered to me what resided within this form.

These meetings lasted throughout our junior year. I would occasionally drive over to Haskell Avenue, park on the street, unlatch the gate to the path that led to the backyard and the pool house, and I usually came unannounced, because Matt never picked up his phone, which added to the erotic suspense of the moment. When I arrived Matt was almost always stoned and usually damp from swimming and either concentrating on rolling a small pile of joints or staring at a movie on the Z Channel he’d watched a few times that week and was still trying to figure out or maybe he was holding a textbook that might as well have been written in Mandarin given the perplexed expression on his face, and sometimes Alex the cat would be lying on his lap staring at me blankly whenever I appeared. Matt was almost always wearing the tight lime-green bathing suit he preferred that year, and though he seemed momentarily distracted whenever he saw me, by a certain point we barely said anything to each other when I’d appear in the open doorway and went directly to sex. Matt didn’t know the niceties of small talk—our presence was enough—and he was usually stiff in ten seconds or already rock hard by the time we stripped and shared the perfunctory kissing that led to the sex. I doubt it ever took longer than ten or fifteen minutes to get off unless I forced us to prolong whatever we were doing, which would end up mildly confusing Matt, though he went with it. I suppose you had to be standing on one side of the aisle to appreciate Matt Kellner’s beauty, but forty years later, sitting in my office high above West Hollywood, I still find Matt’s body the most erotic and beautiful I’ve ever seen and been privy to, and the fact that I had an intimate and hard-core access to all of it leaves me somewhat stunned as I write this at fifty-seven. And yet Ryan Vaughn, who I later confessed my relationship with Matt, wasn’t interested and seemed surprised that I’d been. Not my type, Ryan said. Too Jew-y.

Despite the intensity of the sex and the fact that we could fuck two or even three times on a particular afternoon, there was ultimately nothing to hold on to, no basis to build a friendship, and I’m not even sure, as I said, that Matt Kellner was actually gay, or just a massively horny teenage boy who could go either way depending on what was available. But I didn’t care and maybe I preferred the ambiguity: there were no gay signifiers, just like there weren’t with Ryan Vaughn—everyone was good at maintaining a pose—and it wasn’t self-consciously butch either, it was something more natural and boyish than simply that. Susan Reynolds might have been the only one who knew about Matt—it wasn’t in anything specific she asked, but whenever she mentioned him it had a vaguely teasing air, as if she had certain information that she didn’t want to divulge. She only knew that I had a “friendship” with Matt (quotation marks hers) but no one else I knew ever asked about him so no one seemed to care that we frequently hung out together in the pool house in Encino. Maybe no one asked because Matt and I didn’t interact with each other our junior year—we might acknowledge one another in the hallway by our lockers with a nod, or maybe half-smile if we shared a class or glimpsed each other at assembly or in the parking lot but we rarely hung out in public—we never went to a restaurant or a movie together. Matt didn’t seem to hang out with anyone—and I began to understand Matt preferred it that way; he wasn’t crushed by loneliness or doubt or insecurity—he was simply on another planet. I wanted access to the more popular world that Matt didn’t care about, and hanging out with Matt, and only Matt, wasn’t going to keep that ambition in play our senior year, and so I became alienated from him. On a sexual level I found him porn-star sexy but I never fell in love, the way I ultimately did, for a brief moment, with Ryan—Matt had become a dissatisfying problem that wasn’t worth it. Swimming with Matt in the pool behind the mansion on Haskell Avenue and then stumbling into the guesthouse dripping wet and locking the door behind us and fucking in the lit glow of the aquarium, our bodies tinted blue as we positioned ourselves on his mattress, timing ourselves so that we could come together, were afternoons I found achingly erotic until I didn’t.

I noticed something was slightly off about the pool house that Labor Day afternoon—I sensed it almost immediately when I arrived but it wasn’t obvious and I couldn’t tell exactly what was wrong. Maybe it was due to the distraction that the guesthouse reeked even more pungently of weed than it usually did, or the images of forest fires raging in Riverside I noticed replaying silently on the TV screen, or maybe it was “Ghost Town” by the Specials echoing loudly throughout the space. Matt was wandering around idly looking for something and wearing only the lime-green bathing suit and a string of puka shells collared his neck that I hadn’t seen before, and he was deeply tanned, bronzed, his hair bleached lightly by the sun—a boy who lived in the pool. He didn’t notice me at first as I stood in the open doorway and when he finally acknowledged my presence it was with one of the blankest looks I’d ever seen. “You didn’t call,” he said. “You didn’t answer,” I said. “Ghost Town” ended and Matt looked at the drawer he was rummaging through and when he glanced at me again he finally sighed as I made my way toward him and held his face in both hands and hungrily kissed his mouth, smelling like chlorine and marijuana and suntan lotion. The door was closed. I had already started to undress. Matt slipped off his bathing suit.

I pushed the sex further than it usually went that afternoon, because it might’ve been the last time it would happen. I wanted to make a final impression on Matt and I wanted him to come hard and I kept stopping him from having an orgasm, pushing his hand away from the cock he was stroking, until I was ready, but I wanted him to come first, and then he was clenching up, his legs and ass lifted and spread, panting fuck fuck fuck and while rocking on his back exploded across his stomach and chest, streaking them white—and then I pulled out and came quietly, staring at him as he looked up at me, shaking, his face a confused grimace, breathing hard, grasping the wrist of the hand that was stroking myself to orgasm. Afterward he was lying next to me, a knee raised, his fingers lightly strumming his reddened chest, his panting subsided, his stomach spattered with both of our semen. I turned to look at him: his face and neck were flushed, and his forehead glistened with sweat, and I was close enough to make out the very faint traces of acne on his chin. He seemed distracted and lifted his head to scan the room. Again, in the silence of the pool house I noticed an element missing—a sound, a noise, movement that I associated with the room—but I couldn’t place what it was. My eyes were drawn to the Foreigner 4 promotional poster hanging on the wall, which I’d never seen before. When I asked Matt where he got the poster, he shrugged and said someone had simply left it in the mailbox and he decided to pin it up, it looked cool, he liked Foreigner. Typical, I thought.

“What did you do this weekend?” I asked quietly.

“Do?” he asked back as if he was mildly surprised. He glanced over at me and then rested his head on the comforter we were lying on and fingered the puka shell necklace.

“Yeah, did you do anything?”

“No,” he said flatly. “Nothing. Just hung out.”

“I went to Debbie’s,” I said. “She was having a thing at her house in Bel Air.”

Matt stared at the ceiling and realized he was expected to say something, and without any malice, asked: “How’s your girlfriend?”

“She’s okay,” I said. “Thom and Susan were there. I think Jeff and Tracy are seeing each other. I think they started dating over the summer.”

I realized the moment I said this that Matt had no interest whatsoever in our classmates’ social rituals and dating lives. And he didn’t say anything—just lay there, naked, lightly running his fingers over his chest. He reached for a box of Kleenex by the bed and wiped his stomach off. He contemplated the tissue before tossing it at the wastebasket by his desk. He handed the box of Kleenex to me.

“There’s a new kid,” I said, watching as Matt got up off the bed and wiped his stomach again with a nearby beach towel crumpled on the floor that he also ran through the crevice of his ass and then tossed in the hamper below the recently hung poster of the Foreigner 4 record as he walked over to his desk, where he started rummaging around, his back to me; it was littered with empty cans of soda, comic books, take-out wrappers, frozen-yogurt containers, a soccer ball, a stack of neatly folded T-shirts. I looked around the room trying to figure out what the missing element was and then landed back on Matt. When he turned around I noticed there were traces of our semen lightly draped across his chest that he’d forgotten to wipe off.

“Yeah?” he asked. “What do you mean?”

“There’s a new kid in our class,” I said. “Robert Mallory.” I not only don’t know why I said the name, I was surprised that I even remembered it.

“Oh,” Matt said. “Cool.” “Yeah, it’s just a little weird.”

Matt shrugged and then turned around and dropped to his haunches and kept opening the bottom drawers of his desk, staring into them. He stood up, his hands on his hips, and scanned the room again. “Weird?” he murmured. “Why is that weird?”

“Well, it’s just weird that someone enrolls senior year,” I said. “That’s all.”

“Yeah,” he said. “I guess.”

“Maybe we should just keep to being friends,” I said suddenly.

Matt walked over to a dresser across the room and opened a drawer.

“Did you hear me?”

“Yeah,” Matt said tonelessly. “I just have no idea what you’re talking about.”

“This,” I said, gesturing at the messed-up bed, the stained comforter, the half-empty bottle of baby oil. “Maybe we should lay off this for a while.”

It was too quiet. That sound was missing; an ambient noise I was used to was no longer there. I pulled two tissues from the Kleenex box and wiped myself off.

“You don’t even need to say that,” Matt said, squinting around the room. He reached over to his desk and put on his glasses—he used them for reading but mostly wore contacts.

“Well, I don’t want you to think that I don’t care,” I said.

“I don’t think anything,” he said, glancing over at me, holding it. “I don’t think anything.” His eyes returned to whatever he was looking for. “I mean, what are you doing? What do you want?” He asked this in a quietly frustrated, almost pleading voice.

I pretended that I hadn’t heard him as I reached for my underwear, slipped the briefs on while lying on the bed and then sat up and grabbed my Polo shirt off the floor, again distracted by the silence in the room. And then my eyes glanced over at the aquarium: it was filled with water and the blue and green and purple lights were still glowing but the cover was missing, and it was empty. All the fish had disappeared. The sound of the filters and the bubbling that had emanated from the tank was gone. The filters had been turned off. That was the missing sound.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “What happened to the aquarium?” He looked over, acknowledged it, shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“You don’t know what happened to the aquarium?” I asked. “You don’t know why your aquarium is empty?”

“No,” he said, more concerned with what he was looking for than what had happened to the aquarium. “I came back the other day and I noticed they were gone.”

“What are you looking for?” I asked, annoyed. “Jesus, Matt.” “My pipe,” he murmured.

I saw it resting on the nightstand next to the bed: a brass bowl with an orange glass mouthpiece. “Twenty fish just . . . vanished?”

“Yeah, they’re gone,” Matt said. “It’s weird. I don’t know.” He reached into another drawer, still searching for the pipe. “I don’t remember doing anything to them, if that’s what you were going to ask me. All I know is that they’re gone.”

“Do you think maybe . . . the cat did it?” I finally asked. He looked over at me and we both started laughing.

“You think Alex ate all my fish?” Matt was cracking up. He threw his head back.

“I don’t know,” I said, still laughing. “Would Alex do that?”

“I don’t think so,” he said, convulsing. “But maybe we’ll never know.”

“Why?” I asked, pulling my Polo shorts on.

“Well, the cat’s missing, too,” Matt said, catching his breath. And then we both started laughing again.

I’d like to say that the conversation between the two of us on that Labor Day in 1981 was more consequential than what I’ve recounted here—that perhaps there was closure, a shared sense that we were both moving on from whatever we’d created and continued for the last year; but despite what turned out to be our final shared laughter, I felt I’d embarrassed myself and wanted to leave, and Matt never seemed to care whether I stayed or left. I noticed it was already dark out—school would be starting tomorrow. “It’s there,” I said, gesturing to the pipe on the nightstand. He walked over to it and picked the pipe up, grinning, and I was still grinning too about the mystery of the aquarium, and yet it seemed to be just another example of Matt’s inability to figure things out—there was nothing proactive about him, he drifted along carelessly, he hung up posters left in his mailbox— and as he filled the bowl with a small pinch of weed that he picked out of an open baggie I realized that I was going to be disappearing soon and that he would care about my absence as much as he seemed to care about the cat, the empty aquarium, the world at large. Matt went over to the stereo, bent down and lifted a needle, and the Specials started singing “Ghost Town” again—This town is coming like a ghost town—and I left the guesthouse without saying goodbye.

I drove onto Valley Vista from Haskell Avenue and glided along the deserted boulevard—there seemed to be no one out on that Monday, the unofficial last night of summer, but through the open windows and sunroof of the Mercedes I could smell the charcoal from various grills and hear the delighted cries of children cannonballing into pools, and every so often I’d catch top-forty songs playing from radios in backyards, and I was reminded that even though we lived in supposedly glamorous Los Angeles this was also suburbia, filled with quiet tree-lined neighborhoods, kids riding bikes in the empty streets, swimming parties and barbecues. I was listening to Peter Gabriel’s “Games Without Frontiers” over and over (. . . Whistling tunes we hide in the dunes by the seaside . . .) as I moved from Encino into Sherman Oaks, and I found myself mindlessly heading toward Stansbury Avenue and the school located there. I was originally going to drive past Stansbury and make a right onto Ventura and let it take me through Studio City, where the boulevard became Cahuenga, and then head into Hollywood, cruising along Sunset until I hit Beverly Glen—a circuitous route back to the house on Mulholland—because I didn’t feel like going home just yet. But I drove up Stansbury until it dead-ended into a cul-de-sac where the closed gates of the Buckley School appeared and the brick wall with the school’s name in gold letters greeted its students, carefully trellised with ivy and lit by a streetlamp.

The Shards

amazon.com

$23.49

amazon.comThe school spanned eighteen acres and was mostly darkened that night. There were rooms lit in the library and the administration offices as well as the occasional sodium light that dotted the hillside, illuminating the path up to the sports field, which was visible from the top of Beverly Glen when you were looking downward at the campus but not at the end of Stansbury, where only the deserted parking lot, the bell towers beyond the gates, and one or two buildings were within view—everything else was dark. I parked in the curved driveway next to the entrance gates and lit a Djarum. “Games Without Frontiers” kept building as I sat in the car and smoked the clove cigarette: the sliding guitar, the synth bass, the militaristic cadence of Gabriel’s vocals, the whistled melody adding an eerie vibe to the darkness of Buckley and the black night. Adolf builds a bonfire, Enrico plays with it . . .

And then I noticed something in the stillness of the school.

It was by the library, which was situated adjacent to the parking lot laid out just beyond the school’s gates.

I saw the lone beam of a flashlight traversing over the trees that lined the hillside the library was nestled beneath.

And judging from where the beam emanated it was in the courtyard below the second floor of the two-story building and whoever was holding the flashlight steadied it until the light wasn’t moving anymore, as if the beam was focused on something—I first noticed the light guiding whoever was holding it down the stairs and along the walkway that led into the courtyard, which wasn’t visible from where I sat. And I wondered what it was focusing on: the benches beside the koi pond, the statue of the school’s mascot, the Buckley Griffin—a mythical creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle, a gold life-sized edifice rising up on a stand beside the koi pond—the small waterfall that quietly cascaded into it, the date palms draping over the space.

In the driver’s seat I sat up, leaning my head down, pushing the visor up, to get a better look through the windshield. The beam moved again through the darkness, and then settled on a space just a few feet away from where it had originally been. The movement of the flashlight wasn’t random—it was precise, as if it knew exactly what it was looking for. Was it a night watchman? I wondered. And then I was confused as to whether Buckley even had a night watchman. I turned and craned my neck and saw the darkened security booth that was always manned during the day and there didn’t seem to be anybody occupying it that night—there was only a beige van parked next to it. I thought briefly maybe it belonged to one of the campus groundsmen prepping the school for tomorrow’s reopening.

The beam moved again to yet another angle and I turned down the volume on the Peter Gabriel song and almost immediately heard the high wavering cries of coyotes somewhere on the distant hillsides surrounding the school. Whoever was holding the flashlight had heard them too, seemingly at the same time I did. The beam of light, which was slowly moving again, suddenly stopped and then quickly swung across the hillside as if it was searching for what was emitting these sounds—the faint howling that signified the animals’ hunger.

And then the light was gone, snapped off.

I thought for a moment I’d imagined it but in the next instant knew I hadn’t, and then I realized that whoever was holding the flashlight, searching the courtyard of the library, was probably heading toward the parking lot. This was an assumption my mind made—it was the drama the writer encouraged. But instead of leaving, I waited, hypnotized by the sounds of the coyotes lightly filtering through the silence of the night. The clove was still lit, smoke lightly curling out of the sunroof, and I thought about the movie Halloween. I thought about Matt’s empty aquarium and his laughter over Alex the missing cat, “Ghost Town” echoing out over the darkened pool, the Foreigner 4 poster pinned above the hamper. I suddenly thought about the deserted house on Mulholland waiting for me and couldn’t remember when my parents told me they were coming back—first week of November or was it later? I was worried in a way I hadn’t been; a small dark wave crested over me. I actually shivered, momentarily disoriented. And then I couldn’t hear the coyotes anymore: their howling had subsided. It was completely silent. I waited but didn’t know what I was waiting for.

And then the flashlight snapped back on, blinding me, glaring through the windshield.

Whoever was holding it stood behind the gates, a shadowed figure, maybe six feet away from where I sat, just a black shape, a mass. I didn’t shout or jump in my seat. Instead I simply started the car and quickly drove away, the flashlight trained on me as I turned out of the driveway, glancing in the rearview mirror as Buckley and the beam of light retreated behind me until I was at the end of the block, where I turned off Stansbury and back onto Valley Vista. I immediately headed to Beverly Glen, which would take me to Mulholland Drive and the empty house. I decided not to drive around the city and instead take a Valium from the canister my mother left me, read a few chapters of Cujo and drift off to sleep. If the Stephen King book was too creepy maybe I’d pick up my mom’s copy of The White Hotel and read that instead. These were the thoughts I had as I traveled upward on Beverly Glen, trying to distract myself from the nebulous worry that was floating somewhere vaguely in the distance.

There was a message from Debbie on the answering machine in my bedroom—because of how wired she got from the cocaine she’d stayed up all night and slept through the day and wanted to know where I was; she pleaded for me to call her back, it was so important, her mother was a wreck and Susan’s faking it with Thom and she missed me. But I was keyed up and didn’t want to talk to her—I was suddenly paranoid, even fearful, about how vulnerable I was in the empty house on Mulholland. I turned on all the lights as some kind of warning to the intruder, positive he was approaching, ski mask on, butcher knife clenched in gloved fist, and would bind me with rope and sacrifice Shingy, and wondered what Matt Kellner would have done if I drove back to Encino and asked if I could spend the night. Shingy didn’t want to go outside. Maybe the dog registered the faint howling of the coyotes, which seemed closer than usual, and that’s why he was lightly shaking, bent into himself on his pillow in the kitchen, and I kept thinking I heard someone on the patio and, emboldened by the Valium I’d taken, headed out onto the deck, where I scanned the yard and the blue-lit pool and heard the coyotes roaming the canyons on their nocturnal hunt but saw nothing. The Trawler kept vaguely crowding my mind and I made sure all the doors were locked and the alarm activated. I couldn’t deny it: the air felt charged, electrified even, and though it was warm out on that last night of summer I found myself shivering again, on the veranda staring into the darkness, with expectation, with dread, with the promise of fear fulfilled. I wanted to relax in the Jacuzzi but I was too afraid to sit outside by myself, and so I took another Valium and fell into bed. I couldn’t let go of it: something had come into the city, a presence had arrived, and this was activated by not only the lone flashlight on the Buckley grounds but also by the mention of a new boy in our class, someone who was going to join us, and participate in our rituals and games, our secrets and evasions, the low-key dramas and the shadowy lies. This was the night before we met that boy, Robert Mallory, for the first time.

Adapted from the book THE SHARDS © 2023 by Bret Easton Ellis, published by Knopf on January 17, 2023.

You Might Also Like