Two-thirds of social workers report children living in dangerously mouldy homes

Two-thirds of social workers have witnessed children living in dangerous conditions with excessive levels of mould as they fear choices are being made between eating, paying rent or heating homes.

In what the Social Workers Union (SWU) has called a “national scandal” amid a cost of living crisis that is far from over, 61 per cent of children’s social workers reported young people are living in these mouldy environments, according to the new research among the union’s members.

At a wider level, the 2024 survey found that almost three-quarters of adult, child and mental health social workers (71 per cent) saw the people they support stop turning on their heating to save money over the winter.

This led to 55 per cent of the 716 respondents saying that many of the people social workers support are living in cold, damp homes. Scottish social workers reported the highest level of people living in these conditions (69 per cent), followed by those in northeast England (67 per cent), where almost all (94 per cent) of social workers surveyed also reported people they support had been forced to stop using their heating to save money.

A social worker told the researchers: “There has become a choice between eating, paying rent, or heating their homes. We are supporting more with food and energy support than ever before.”

Another said: “Parents are having to choose between buying food for children and heating their homes. Energy bills are simply not affordable. Respiratory infections in children have increased due to living in cold, damp homes. Children’s sickness has impacted their school attendance.”

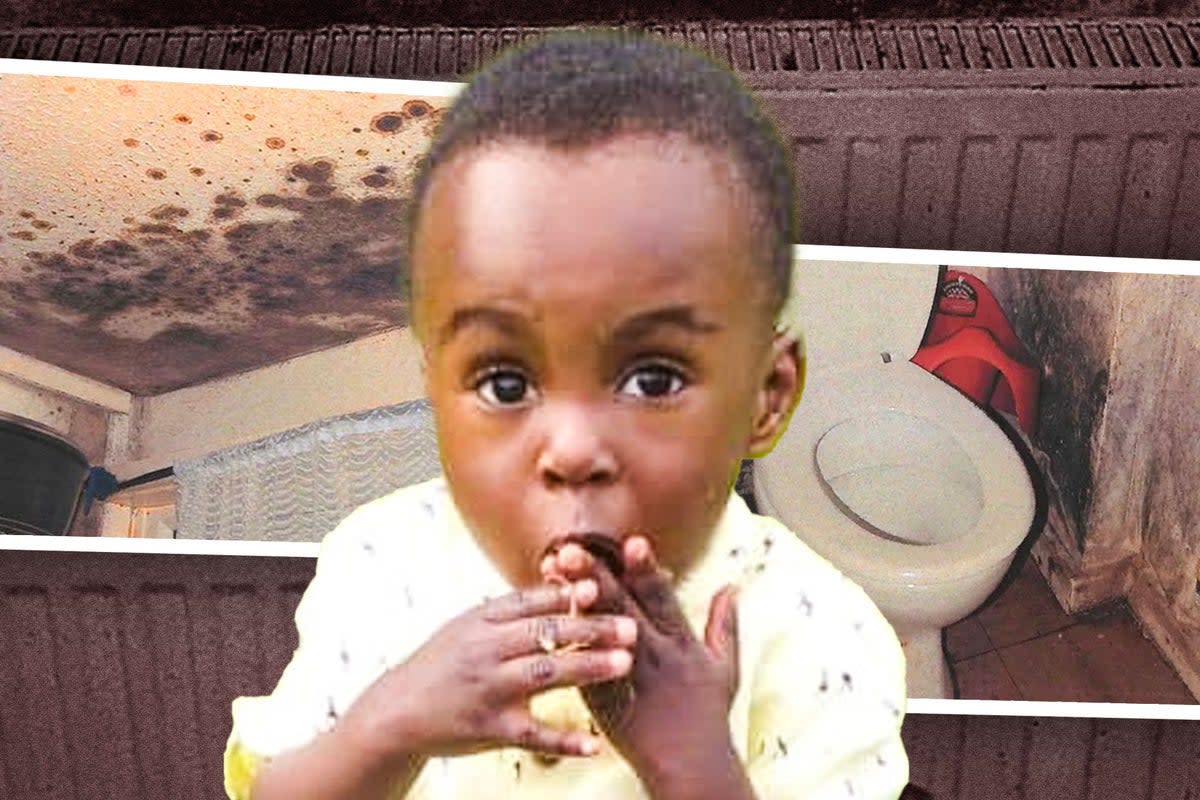

It comes after a coroner ruled that two-year-old Awaab Ishak’s death in December 2020 was caused by prolonged exposure to mould in the flat where he lived with his mother Aisha Amin and father Faisal Abdullah in Rochdale, Greater Manchester. His parents had complained to the provider about mould multiple times.

John McGowan, General Secretary of the SWU, said: “While politicians try to kid themselves that the cost of living crisis is over, the reports from our members show just how dangerous this winter has been.

“All too often social workers are reporting seeing people living in substandard and dangerous housing. This happens in all parts of the country, but we know that people living in the private rented sector can be among the worst affected.

“Children living in cold, damp, mouldy homes is a national scandal and we need to see drastic action being taken to fix Britain’s broken energy system.”

The UK government said there were around 1.5 million non-decent rented homes in England in 2022 – 1 million of which are private and 430,000 of which are social – although this does mark a drop from the roughly 1.9 million that there were in 2015.

Dr Cath Lowther, General Secretary of the Association of Educational Psychologists, said young people living in damp and cold conditions are facing “adversity, plain and simple”, unable to thrive and develop.

She said: “Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are known to have a long-term negative impact on all aspects of people’s lives. This involves significantly increased risk to physical health as well as further risks to mental health and achievement in school. Nobody can concentrate on schoolwork when all they can think about is trying to keep warm. And how confident will a child or young person feel about inviting their friends over to such a home?

“If the government is serious about improving the lives of our children and young people, starting with safe, adequate housing needs to be a priority.”

Nearly a quarter (24 per cent) of social workers polled also reported that the people they work with who have a disability or health condition cannot afford to run medical equipment, while 15 per cent told of seeing disabled people whom they support unable to charge their mobility devices due to the high cost of energy.

Simon Francis, coordinator of the End Fuel Poverty Coalition, said: “The price households pay for their energy is still higher than in 2021 and levels of energy debt are soaring. Meanwhile, the wider cost of living crisis means people simply can’t afford to keep the heating on when it’s needed most.

“What we need to see is a much faster rollout of programmes to improve the energy efficiency of buildings and bring down the cost of energy. The reality is though that there will also need to be a structured programme of financial support announced well in advance to help people through next winter.”

Warm This Winter campaign spokesperson Fiona Waters said: “This is a heart-rending and all too familiar story where the most vulnerable are at risk because of our broken energy system and we need urgent change before even more children, the elderly and others become ill or worse.

“As a rich country, at the very least we should be giving our people warm, dry, healthy homes to live in. That’s why we need long term solutions such as expanding homegrown renewable energy and a mass programme of insulation to bring down bills once and for all so these appalling living conditions are banished to the past where they belong.”

A spokesperson for the UK government said: “Everyone has the right to a warm, secure and decent home, and we expect landlords to meet our energy efficiency standards before letting properties.

“We are introducing a Decent Homes Standard in the private rented sector for the first time and have also passed the Social Housing (Regulation) Act, which will deliver significant changes across the sector to ensure landlords are held to account for their performance.

“Our landmark Renters Reform Bill is progressing through Parliament and will deliver a fairer private rented sector for both responsible tenants and good faith landlords.”

They added that the government published new damp and mould guidance for social and private rented landlords in September 2023.

They said the government has allocated £20 billion for energy efficiency over this parliament and next, while support to households to help with the cost of living is worth £108 billion between 2022 and 2025.