The value of silence

Life is "filled with noise" but not at a Finnish hairdresser's that has introduced a "silent service" for customers.

At Kati Hakomeri's salon in Helsinki, customers can ask to avoid "polite chitchat about the weather, weekend plans and future holiday destinations", said The Times, and she "appears to have found a gap in the market because demand for the option in her salon has proved buoyant".

"I'm an introvert myself and I understand how uncomfortable it can be for a client to have to make small talk," she told Helsingin Sanomat. The quiet could prove valuable because in this "cacophonous world", silence is "the window to a wealth of wonders", said the BBC.

'Louder and louder'

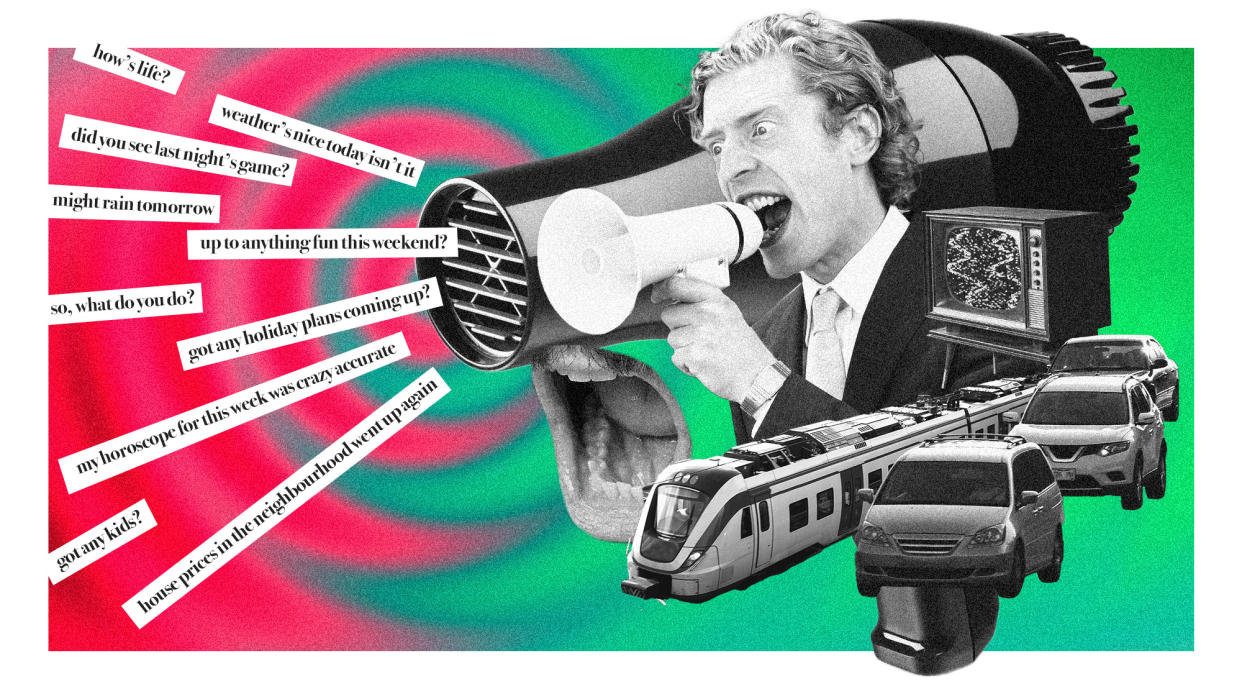

If there's "such a thing as a perennial grumble, noisiness might be it", wrote Justin Zorn and Leigh Marz for Vox, but "these days", life is "not just loud", there's "an unprecedented mass proliferation of mental stimulation".

The "trajectory of modern life seems inexorable", including "more cars on the roads, more planes in the skies, more whirring appliances, more buzzing and pinging gadgetry".

There are "louder and more ubiquitous TVs and speakers in public spaces and open-plan offices", and in Europe, an estimated 450 million people, or 65% of the population, live with noise levels that the World Health Organisation regards as hazardous to health.

Also in Europe, 12,000 premature deaths each year are caused by the stress and cardiovascular disease brought on by excess noise, found the UN Environment Programme.

'Prattle sabbatical'

"In an industry (and a world) filled with constant yapping", it's "no surprise" that the silent haircut option has had a "huge take-up", wrote Celia Walden in The Telegraph, because what could be more appealing than a "prattle sabbatical?"

"At its core", interaction with hairdressers, cab drivers and others feels like "filling silence for the sake of it", wrote Helen Coffey in The Independent, because we "believe it is expected of us", though "neither party is invested in the conversation", so its draining to keep up the "charade".

In 2019, Uber offered a "quiet mode" option for some journeys, so if passengers were "not in the mood for a chatty driver", they could "avoid small talk during their ride", said the BBC. Not everyone approved: writing on Twitter, one user said that this suggested that "wealthy people can buy their way out of interacting with the poor, who aren't worthy of their attention".

But more quiet in our lives brings "concrete effects", wrote Michael Harris in the Globe and Mail. He noted that scientists who gave lab mice daily doses of silence found that cells in their brains grew faster, while constant noise "stunted brain growth" and schoolchildren "placed in classrooms by noisy subway tracks had lower reading levels than those who worked on the quieter side of the school".

Perhaps the ultimate value of silence is that it has no economic value. "Silence", wrote Swiss thinker Max Picard, is "the only phenomenon today that is 'useless'", in that "it does not fit into the world of profit and utility; it simply is" and "cannot be exploited".