Why the trope of the fat, unlikeable character in books needs to end

Looking for more of the best deals, latest celebrity news and hottest trends? Sign up for Yahoo Lifestyle Canada’s newsletter!

What’s the first indication that a new character in a book is going to be unpleasant or undesirable? They’re described as fat.

Well, usually not “fat” but rather, “rotund” “heavy-set”, or some other euphemism that denotes their large size. Whenever I read of the entrance of a character whose girth is mentioned immediately, I know there is a substantial likelihood this person will be rude, over-bearing, or in some way create conflict for the protagonist.

Having read more than 400 books in the past year, I can confidently say that the use of fat to denote an unpleasant or cruel person is not a passing fad - it’s a trope.

Consider this description from “The Perfect Alibi” by Phillip Margolin.

“The older woman was so obese that she barely fit in her chair. Fat rolled over the top of her stretch pants, and her dough-like arms and face were rounded and undefined.”

This is the first description the reader gets of this character. With this description, are you expecting to like this character? Of course not. This description is meant to gross us out, and make assumptions about the quality of this character. And indeed, she is confirmed to be pushy and arrogant. But Margolin isn’t done with using this character’s size to denote her negativity. He also mentions she “struggled to her feet” and that the protagonist had to walk slowly “so the heavyset woman could keep up.”

Meanwhile, in the following paragraph, one of the “good guy” main characters is introduced as “32 with long brown hair, brown eyes, and the rock-hard body he had developed while competing on the University of Washington’s nationally ranked crew.” The contrast is intentional. Also of note, the fat character is mentioned as fat several times before we learn her name, whereas the man with the rock-hard body is mentioned by name before we get a description of his body.

The trick is effective. We as readers correctly guess that the fat character is going to be unpleasant, and the fit character is going to be likeable. But let’s look carefully at both descriptions. Why would a description of a fat belly hanging over pants, or large arms and face denote a bad person? What does this character’s mobility have to do with her worth as a human? The answer, of course, is that it doesn’t.

ALSO SEE: How letting go of body standards led to my biggest career milestone

Objectively, being fat has no correlation with a poor personality. Does knowing that I fit the description of this character exactly, right down to the difficulty walking, give you any indication of what I am like as a person? If you met me on the street, you would undoubtedly find me to be a pleasant person with a good sense of humour, a kind heart, and an identity as complex as anyone else. But what if before I arrived, you were given a description of me similar to the one of Margolin’s character. Would you be expecting to like me?

In case you think I am picking on Margolin, I should note I enjoy his books very much. In fact, that’s what makes the use of this trope even more irritating. Frequently, I will be engrossed in a book, often by a favourite author, and the blatant fat-shaming will appear and pull me out of it. Just as it is more painful when a loved one says something hurtful than when someone you dislike does, seeing an author you love weaponize fatness feels like a personal attack when you fit the description they are using. It causes you to question whether this author really considered you as a target reader for their book. It makes you aware that others are making assumptions about your personhood based on your appearance.

Setting up a character to be unpleasant isn’t the only way fat is used as a device. If a character is described as “plump” or another similar euphemism, there’s a good chance they will be matronly and/or incidental. These fat characters are exceedingly kind and maternal, or they are expendable. They’re never sexual, three-dimensional, or stand-alone. They exist to highlight and support the protagonist or to further plot. Though less damaging than equating fat with bad, this still reinforces the attitude that fat people are invisible. They are characterized and valued only by their relationship to other, subjectively more important people. There is a reason so many characters on television have a chubby friend. Rarely do these characters have a life outside of the main narrative.

Occasionally in books, fat people are used as props. What is the easiest way to convey that a main character is having an unpleasant travel experience? Seat them next to a fat person. The main character can then complain in their heads about feeling crowded, body odour, gross eating habits, and other stereotypes of fat people, and the reader will instinctively feel sympathy for this character trapped beside this disgusting fat person. The fat person remains nameless, and usually faceless. They are not a person; they are a device.

ALSO SEE: How pregnancy made me fall in love with my body again

On the rare occasion that we get a fat protagonist, they are never obese, but rather “carrying an extra twenty to thirty pounds on their frame”, and there is almost always a comment about how they are insecure about it. There can be a likeable fat main character, but they have to feel badly about being fat. And they can’t be too fat.

It may seem as though I am being too sensitive about these tropes. They are tropes, after-all, and aren’t tropes supposed to be reductive and generalized? Surely reading the odd comment isn’t that harmful. Consider, though, how hearing fat being equated with bad or invisible repeatedly, and in so many works of literature, affects readers who are fat.

At some point, we internalize the equation, and it manifests as self-hate. We begin to think this is how we are viewed by the general public. We deduce that our stories are not important to tell because there is no one who looks like us in the books we read, at least not in fiction. I reiterate – I have read over 400 books in a year, and at least one fat-shaming comment exists in nearly all of them. It’s a lot to take in as a fat person.

These stereotypes in literature start early. Consider some favourite kids’ books. Who are the fat characters? Rarely are they the prince or princess, or even the protagonist. They’re the villain, or they’re the incidental character who supports the protagonist and blends into the background. Many times, they don’t exist at all. The idea that fat people are either bad or not important enough to be the lead character is instilled in children from the time we begin reading to them, and is reinforced as their reading develops into adulthood. Is it a wonder that being fat is such a taboo in real life?

ALSO SEE: Here's why more people are turning to therapy to treat their chronic acne

When pressed, most would agree that using fatness to elicit a negative response is bad. So why do authors keep doing it? Because it’s easy and it’s effective. Why spend a paragraph giving real evidence that a character is unlikeable, when an insulting description of their body will set the stage with a much lower word count, and a more visceral response. Authors know that society views fat as gross, so they employ that stereotype to their advantage. Then, the descriptions of fat as gross strengthens the stereotype in a vicious circle that benefits authors and harms real fat people.

Writing is difficult – I know this from experience. Sometimes it’s easier to take a shortcut and fall back on well-established archetypes. But when these archetypes hurt readers, it’s time for us to retire them. I challenge authors to include fat characters in their works that defy these tropes. Allow a fat protagonist to be fat without it being their defining feature. Let them have a complex story. Let them have sex. Let them be confident. Let them be respected for something other than being confidently fat. Show fat readers that they are seen and they matter. Show readers who are not fat that fatness is not a monolith – there is as much diversity within our community as there is within society at large.

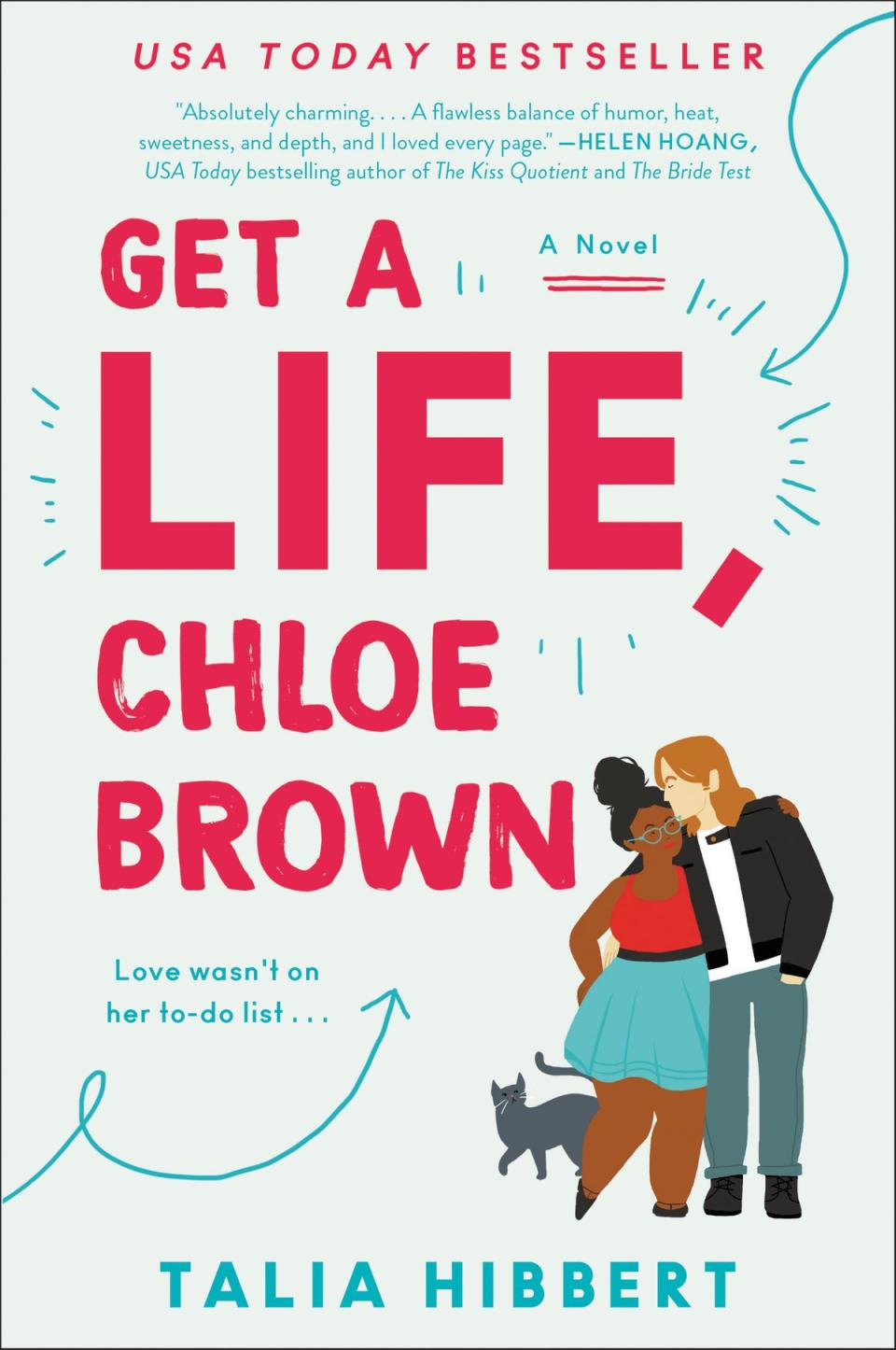

It is possible to do this and write a compelling story, even a romance. The main character in Talia Hibbert’s romcom novel “Get a Life, Chloe Brown” is both fat and disabled, and she is a fully-dimensional character with a wide range of experiences, including a love life. Her body is part of who she is, it doesn’t define who she is.

This book is one of the rare books I have come across to not only refuse the usual tropes about fat people, but to give a positive representation of fat people. It’s no coincidence that this is my favourite romcom, and that Talia Hibbert is one of my favourite authors. Not only can it be done, it makes for a better book.

The next time you are reading a book and you see a description of a fat body used to foreshadow a negative character, ask yourself what about being fat makes this character bad? The answer is always “nothing.” Replace that description instead with the actual negative traits this character possesses. Remind yourself that this character is bad and fat – two separate and unrelated descriptions. When we are mindful of what we are reading, we can make sure we aren’t unwittingly buying into tropes that harm others, or ourselves.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA! Follow us on Twitter and Instagram and sign up for our newsletter.