Can Ferrari, the Winningest Team in F1 History, Get Back on Track? We Ask an Expert

This year marks the 74th anniversary of Formula 1, the ne plus ultra of motorsport, and James Allen has been covering more than 30 of those seasons as a journalist, broadcaster, and industry insider. In doing so, he’s seen Maranello’s scuderia go through its share of heydays and humiliation, and witnessed the sport’s recent acceleration into the global consciousness.

A graduate of the University of Oxford, and now CEO of Motorsport Network, Allen inherited his love for racing from his father, a works driver for Lotus and a class-winner at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1961.

More from Robb Report

One of Jay Leno's Favorite Mechanics Was Just Arrested for Theft and Fraud

This Ferrari Has a Top Speed of 15 MPH. It Could Fetch $1 Million at Auction.

“As a kid, I started to understand the mentality of the people that drive the cars, run the racing teams, and organize the championships,” says Allen. But although hooked on automotive competition, “it was always clear to me that narrative storytelling was where my strength lay,” says the author of books on Formula 1 greats Nigel Mansell and Michael Schumacher.

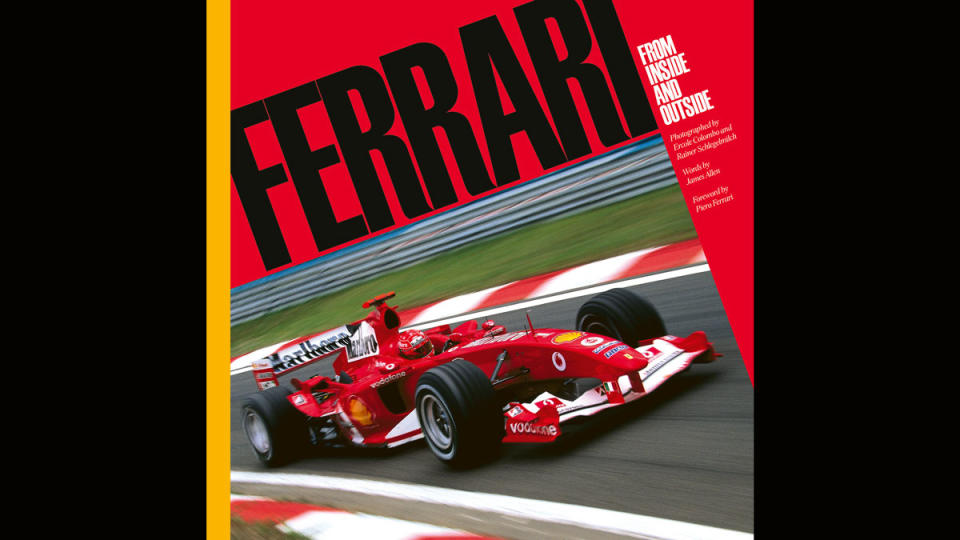

Allen recently talked to Robb Report about his latest work, Ferrari: From Inside and Outside, a nearly 300-page coffee-table publication released last May. Here, he also shares his insights on former champions, what’s contributed to the sport’s recent boom, and the 2024 season currently underway—a 24-race stretch in which Ferrari finds itself second in the World Constructors’ Championship before heading into the Australian Grand Prix next weekend.

Is there a period you consider the golden age of Formula 1?

I would say that there isn’t just one. Senna, Prost, Mansell; these guys were proper gladiators. They took no prisoners. They were very unforgiving in the cars, because they were very determined and very committed. But, also, the cars were much safer than they had been in the days when my dad was racing, where you didn’t really want to get too close to each other or get involved in an incident because you could die. [The cars] still weren’t completely safe, as the accidents of [Ayrton] Senna and Roland Ratzenberger—in the same weekend in 1994—showed us. But, nevertheless, [drivers] could play very high-speed games of chicken with each other. That was unbelievably thrilling and created a real wave of excitement about Formula 1.

And then I would say the other [period] was the early 2000s. Apart from the two seasons that Schumacher dominated, in 2002 and 2004, the championships around that time were very exciting, with very committed individuals who were all trying to match up to the level of Schumacher and Ferrari.

Were you close to any drivers during that period?

I got to know Senna quite well and had many conversations with him. I cherish those memories. He was certainly a unique and remarkable human being. I wrote two books with [Michael] Schumacher and got very special inside access to Ferrari at the time and could see what a winning machine looks like.

What factors contributed to Formula 1 progressing from a Eurocentric sport to one with immense global popularity?

Until recently, 60 percent of the audience was based in Europe, but that has changed in the last few years. When Bernie Ecclestone was running it, he pushed hard to have many new races in Asia in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. And then, in 2017, Liberty Media was in control and realized that Bernie’s weakness was that he had never really succeeded in America. [Liberty Media] had the toolkit to do that. They loosened things up as far as the rights of drivers and teams to do social media and video filming in the paddock—all kinds of things that Bernie wouldn’t allow because he just really didn’t get the digital revolution, and Liberty did. They pulled all the right strings, and, obviously, Drive to Survive was a huge success.

The other thing is the cost cap, which is only in its relative infancy. The weakness of Formula 1 has always been that there was no proper financial regulation. The bigger teams could always run away and spend as much as they wanted to maintain their advantage. Whereas over the next few years, you will see the field closing up more and more. Formula 1 will not only look spectacular and feature lots of great personalities, but it will also be incredibly competitive racing.

When, and how, did the idea for the book Ferrari: From Inside and Outside come about?

I’m president of Motorsport Network, which is just a media business now, but a couple of years ago it also included various other assets, one of which was a very large photo library called Motorsport Images. It had the collections of Rainer Schlegelmilch and Ercole Colombo, two absolutely legendary photographers who are fortunately still with us today, though retired. The owner of the archive said he would like to do something featuring those two, but he would leave it entirely up to me as to what that was.

I got together with them and they felt that the project should be around Ferrari because Ercole had been Enzo Ferrari’s photographer and he had some unbelievable access and amazing images from behind the scenes. And Rainer definitely styles himself as a shy outsider and was very much into the Magnum school of reportage. So it was Ferrari from inside and outside.

How much Access did Ferrari give you for the project?

Everybody was very happy to participate, from Piero Ferrari and Luca di Montezemolo to Stefano Domenicali and Jean Todt—even Mauro Forghieri just before he passed away. They were all happy to contribute, and contributed richly. I’m very grateful for their time and their insights.

What was the production time for the book?

About 18 months. Of course, that was helped by the fact that there are only about 15,000 words in it.

What are some of the intangibles that make Ferrari the winningest team in Formula 1 history.

Success in a team endeavor is always about the people. That’s true with any team, whether it’s Red Bull today, Mercedes five years ago, or Ferrari in the Schumacher-Todt era. The key is strong leadership. When Ferrari has been successful, it’s been despite the politics, because they have a more complex political structure around them than any other Formula 1 team. And, up until about five years ago, the Italian media had a lot of power. Todt, though, protected the team. You could see the calmness of the drivers, the mechanics, and the technicians who could get on with their work without being blown around by the media.

Other than Enzo, which individual has had the most profound impact on Ferrari?

Undoubtedly it would be Luca di Montezemolo. During the late 1970s, Enzo Ferrari brought in Montezemolo—then in his late twenties—to be the team manager. He eventually went off to other things in the Fiat empire, but came back again [in 1991] and tidied up not only the road-car side but also sorted out the Formula 1 team. He was the one who hired Todt and finally Schumacher. Montezemolo created the environment that allowed all of Ferrari’s success in the late 1990s and early 2000s to happen. He’s the most consequential figure in Ferrari since Enzo.

In your opinion, does Ferrari’s current Formula 1 team have the ingredients to replicate past glory?

That’s a tricky question to answer. They have the resources. They have, I believe, a very good, strong leader in Fred Vasseur, who knows what it takes to succeed in motorsport. And they’ve got the drivers in Leclerc and Sainz to take on the best in Formula 1. But they have a fair amount of politics they have to deal with. It’s really about keeping stability within the team and giving it protection from outside forces, which is always the key bit to get right.

You’ve written books on both Nigel Mansell and Michael Schumacher, what are the common denominators you find with Formula 1 champions?

The thing that marks them out is commitment. They were two particularly committed individuals, and Senna was the most committed I’ve ever met. Most of the great champions—whether it be Verstappen, Hamilton, Schumacher, Mansell—their commitment is unbelievable. And with that comes a tremendous work ethic. [Mansell and Schumacher] were relentless in their demands on the team—seeking every tiny gain. They just left no stone unturned in trying to beat the opposition. And there is a relentless desire to self-improve. Whether you’re a driver, or an engineer, or a team boss, you cannot stand still, you have to constantly self-improve.

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.