New York’s Rubin Museum is closing its doors — but will live on as a ‘museum without walls’

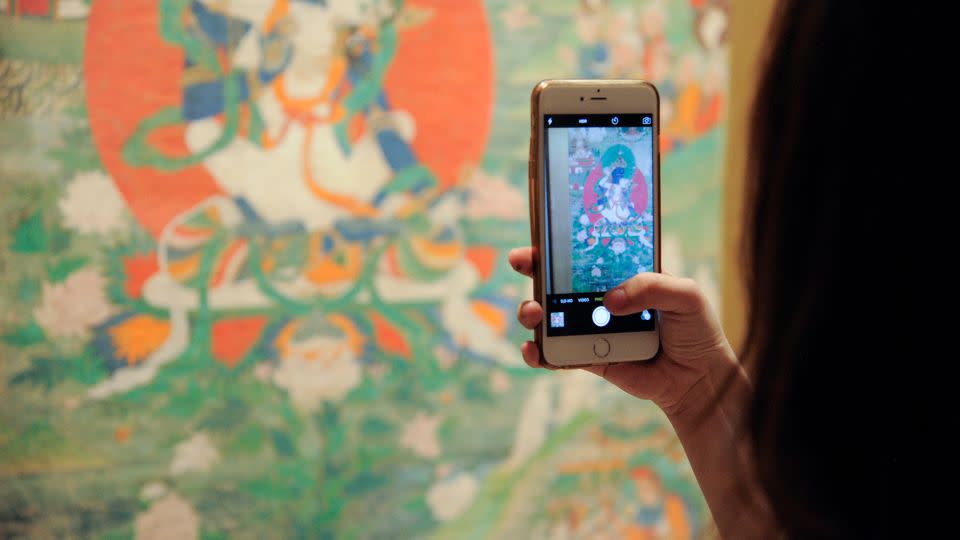

New York’s Rubin Museum of Art, home to one of the world’s largest and most important collections of Himalayan art, announced on Wednesday that it will close its doors in October.

The museum, founded by Shelley and Donald Rubin two decades ago, houses nearly 4,000 Himalayan art objects, introducing visitors to elaborate paintings, religious sculptures and iconography from the region. But it, like many museums, has faced challenges in recent years, undergoing staff cuts and becoming embroiled in the debate around repatriation of artifacts with questionable provenance.

The museum said in a public statement on its website that it will sell its Manhattan building to become a “museum without walls.” A new “global museum model” will see the Rubin loaning out items from its collection and organizing traveling exhibits, the statement added.

“In our new incarnation, we are redefining what a museum can be,” Noah Dorsky, the museum’s board president said in a press release, adding that in recent years the role of a museum has “evolved dramatically” — as have the needs of the communities they serve.

“Building and sharing this collection of Himalayan art was one of my family’s great joys,” added Shelley Rubin. “While it has been a privilege to welcome visitors to the Rubin in New York over the last 20 years, our anniversary inspired reflection on how we can achieve the greatest possible impact well into the future.”

“The result is the firm belief that a more expansive model will allow us to best serve our mission — not changing ‘why’ we share Himalayan art with the world, but ‘how’ we do it,” she added. “Bold change has always been in the Rubin’s DNA, and we are excited to embrace what our future as a global museum has to offer.”

The museum said it will expand its research and further invest in videos, podcasts, essays and other educational resources. It committed to “supporting and elevating” contemporary artists exploring Himalayan art — much of which is rooted in Buddhist traditions — and will continue research into the origins and acquisition of artifacts in its collection, saying it “vehemently opposes the trafficking of stolen or looted cultural items.”

The Rubin recently repatriated three items in its collection that were determined to have been stolen, including a wooden carving returned to the Itumbaha monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal. The monastery’s new on-site museum was set up with help from the Rubin and local museologists.

Announcing the closure of its Manhattan space, the Rubin sought to allay fears about its finances; a spokesperson for the museum told CNN in a statement that the decision to close its physical doors “is being made from a position of financial strength.” (The museum went through a restructuring in 2019, reducing staff, opening hours and programs, citing a need for “long-term sustainability.”)

“The museum also achieved its highest-ever fundraising numbers in 2022 and 2023,” the spokesperson added, further noting that the Rubin’s endowment — some $150 million — “is of a scale of major NYC institutions and sets them up very well for the future (as) outlined.”

“The significant resources required to own and operate a building in New York City will now be focused exclusively on our collection, exhibitions, programs and community of artists,” the museum’s executive director, Jorrit Britschgi, told CNN in an email. “In other words, this new model means more funds spent on sharing art, supporting artists and scholarship, and expanding on our flagship programs like Project Himalayan Art.”

“In this decentralized model, we will be active in more geographic locations as well as non-traditional spaces, from parks to festivals and fairs,” Britschgi continued. “By doing so, we will exponentially expand the audiences we are able to engage with and inspire through Himalayan art.”

“The art in our galleries teaches us that change is constant and inevitable,” Britschgi wrote in an open letter published on the Rubin’s website this week. “We take inspiration from this, as we boldly let go of an old model and redefine what it means to be a museum in the 21st century. We will build on partnerships and collaborations with people from the Himalayan region, diaspora, and beyond, and make our offerings available globally, supporting research, artistic expression and creativity.”

The Rubin cited its work with Nepal’s first ever national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the collaboration with the Itumbaha Museum and the Mandela Lab — which provides interactive experiences for emotional learning through Buddhist teachings — as examples of how it will fulfil its new role.

But not all are convinced by the merits of closing the New York space.

Ian Johnson, a senior fellow at the Centre for Foreign Relations, meanwhile lamented the museum’s closure as a “disaster for Tibetan art,” with the USA’s former Ambassador to the Asian Development Bank, Curtis S. Chin, responding to his post to say he was “saddened by this news.”

“The Rubin did outstanding works over the years,” Johnson told CNN in an email. “In terms of Tibetan art, the (museum) was one of the few venues in the world that highlighted it, along with other Himalayan art — especially Nepalese — as separate. A lot of the time, we are shown Tibetan art as part of Chinese art — as an appendage because Tibet is now part of China. But this erases the region’s distinct historical identity.”

The closure will see some 40% of the Rubin’s staff lose their jobs — mostly those in “front-of-house roles,” a spokesperson for the museum told CNN. The museum will maintain an office in the city and a secure location where researchers can access artifacts that are not out on loan.

The Rubin will officially close on October 6, and its final exhibition will be the upcoming “Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now.”

A number of existing projects — including “Project Himalayan Art,” an archive of physical and digital scholarly resources, as well as a curriculum used by schools and teachers in New York City — will continue.

The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room, a visitor favorite, will be relocated to a new home.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com