A birthday salute to NC’s Bromo-Seltzer King, who lived a ritzy life of yachts, excess

For nearly a century, every fool who mixed red wine with whiskey, scarfed chili with chocolate cake or shamelessly tore through a button-busting buffet found relief in Bromo-Seltzer — the blue-bottled elixir crafted by a Tar Heel chemist.

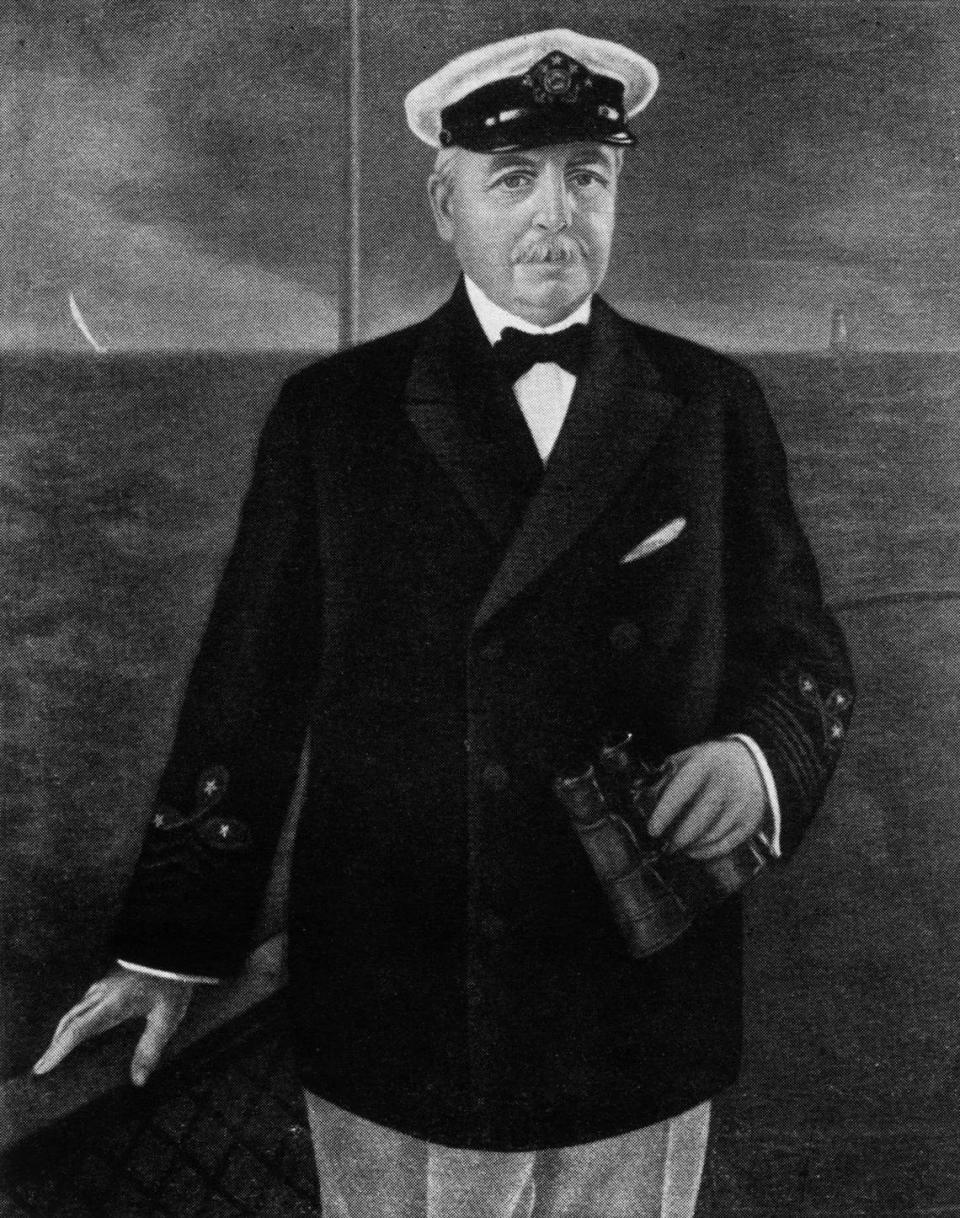

Isaac Edward Emerson, once a chemistry student at UNC-Chapel Hill, invented a miracle cure so popular in the 1880s it bought him three mansions, three yachts and a 12,000-acre plantation in South Carolina.

As a largely forgotten titan of the Gilded Age, he toured the French Riviera, hobnobbed with presidents, consorted with bootleggers, threw lavish parties and laughed in the face of polite society — all thanks to his effervescent tummy salts.

So today, in honor of Emerson’s 165th birthday, I will salute his flamboyant memory by ingesting something truly regrettable.

Martinis with hot dog water come to mind, consumed with a hat-tip to this patron saint of overindulgence.

Yachts, horses and fast cars

“Isaac Edward Emerson was a force to be reckoned with,” wrote his biographer, Bob Luke. “Bromo-Seltzer made him a millionaire many times over. His wealth enabled him to engage in globetrotting while collecting yachts, horses, fast cars, buildings and expansive estates.”

Much of this tribute comes thanks to “Bromo-Seltzer King,” the excellent book Luke wrote in 2020, which traces Emerson’s opulence to his roots on a Chatham County farm.

Luke notes that the young chemist came of age as the nation was shedding its agricultural past for the fast-paced world of telephones, automobiles and other gizmos.

With a little gumption, and a healthy disregard for the lives of ordinary people, a titan of Emerson’s era might make enough money to run champagne through the kitchen faucet.

Which Emerson nearly did.

“He made sure the finest wines and spirits flowed regardless of venue,” Luke wrote, “aboard ship or one of his estates — and regardless of the law of the land.”

But even in his Chapel Hill days, Emerson began blossoming into a flamboyant dandy, always dressed to the nines and game for a laugh. Whether he was on campus or working in a pair of Franklin Street pharmacies, the ladies noticed his good height, ample brown hair, blue eyes and “florid complexion.”

He stubbornly pursued one of these admirers, Emma Askew Dunn, though she was a divorcee — the social equivalent of kryptonite in the 19th-century South. But he thumbed his nose at the haters, married Emma and split for Baltimore without even graduating.

Headaches and hangovers

As a pharmacist, he’d already noticed the stream of patients complaining of pains from overeating or too much drinking. And in Baltimore of 1883, he perfected the concoction made with sodium bromide — a toxic substance that would endure as an ingredient for nearly a century.

Emerson’s fast success came not just because Bromo-Seltzer actually helped with headaches and hangovers, but because its spirited young inventor had a ground-breaking gift for marketing.

Ads for Bromo-Seltzer appeared in newspapers, in streetcars, on horse-drawn wagons and on a 289-foot clock tower with the letters B-R-O-M-O-S-E-L-T-Z-E-R replacing the numbers on its face.

His newly formed drug company, totally unregulated at the beginning, dreamed up a thousand slogans that hinted gently at binge drinking: “For that out-o’-sorts feeling,” went one.

And with his millions, he spent everywhere — including UNC-Chapel Hill, where he gave money both for the Wilson Library and to build Emerson Field, which is now the site of The Pit.

“As was true of the British empire of the time,” Luke wrote, “it could also be said the sun never set on Bromo-Seltzer.”

To further describe his life — which included starting the Maryland Naval Reserve and buying his own squadron of ships to fight in the Spanish-American War — would take another week’s column. I recommend Luke’s book instead.

But the Bromo-Seltzer King died in 1931 with a fortune estimated at $381 million.

His only child, Margaret, divorced a drunken and abusive husband and married the even-richer Freddy Vanderbilt, who was onboard the Lusitania and died when the Germans torpedoed it in 1915. She would marry and divorce twice more.

I think they hardly make lives so interesting anymore, at least not as elegantly catered and without such exquisite hats.

Let us drink a toast or 20. There’s medicine tomorrow.