Boris Johnson could become longest-serving caretaker PM in history

Boris Johnson has, throughout his career, defied convention and torn up precedent. He may finally have agreed to leave office, but the Prime Minister won’t do so without one final act of defiance.

Mr Johnson is understood to have insisted he will stay in office until the autumn, giving himself an unprecedented months-long period in office despite having announced his intention to resign. No other prime minister has clung on for so long having been forced to resign.

Leaving aside death, there are two main ways that a prime minister leaves office – after losing an election or resigning.

In the case of the former, it is usually straightforward. The outgoing prime minister resigns on the day of the election result and is replaced immediately by his or her successor.

The only exception to this was Gordon Brown in 2010, who held on for five days in the hope of cobbling together a coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

In the case of a resignation, things have grown more complicated and for one simple reason: ordinary party members were given a say.

Removing a prime minister from office has changed little over the years, but choosing a successor was once incredibly simple and quick.

Anointed successors

Sometimes, as with Anthony Eden in 1955 when Winston Churchill resigned due to ill health, there was only one viable candidate who simply walked straight into office.

Things were equally quick for Eden himself when he was eventually forced out over the Suez Crisis and his own poor health in 1956. He resigned on January 9 and a day later, after a quick gauging of opinions in the Cabinet, Harold Macmillan was chosen as his successor.

Macmillan’s own departure from office would prove to be rather controversial. He advised the Queen that Alec Douglas-Home was best placed to form a government, despite Rab Buttler being more popular.

The Queen subsequently invited Douglas-Home to form a government and Tory ministers and MPs, unwilling to undermine the palace, fell into line.

Whatever the controversy, the whole debacle was over within a few days.

Contested handovers

Even when the succession has been contested in the past, the handover was rapid.

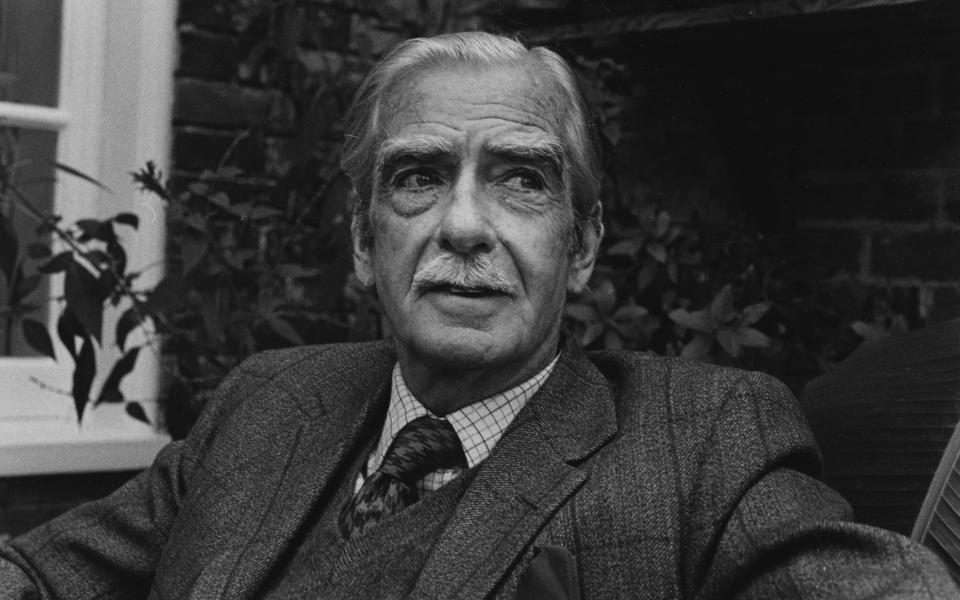

This was true both of the defenestration of Margaret Thatcher in 1990 and the far more amicable end to Harold Wilson’s second premiership in 1976.

Wilson shocked Westminster and the country by announcing out of the blue on March 16 that he intended to leave. Throughout his time in office, Wilson had partly been able to keep the wolves at bay by the simple fact that he had so many rivals for No 10.

This meant that there was a wide range of candidates who stood to lead the party and become prime minister in 1976, representing all wings of the party.

Nevertheless, the first ballot of MPs was held nine days after Wilson announced his intentions, the second five days later and the third another five after that, on April 5. James Callaghan, the winner, took office the same day.

For Mrs Thatcher, things were more brutal but equally swift. She was challenged on November 14 by Michael Heseltine, the first ballot of MPs took place on November 20 and while Thatcher won, the 40 per cent vote against her was enough to push her to withdraw from the contest two days later.

A second ballot without the PM was held on November 27 and the next day Sir John Major took over.

Again, the need only to consult Conservative MPs made the process incredibly quick.

Drawing out the process

It’s only in the 21st century that prime ministerial successions have become drawn-out affairs.

Sir Tony Blair had the longest interim period of all at six weeks and six days, but that was the result of unique circumstances.

After 10 years of factionalism, Mr Brown was champing at the bit for his turn in office. Sir Tony had said before the 2005 election that he would not lead the party into another election and in September 2006 he announced that he would step down within a year. Eight months later in May 2007, he put a date on it of June 27.

That was intended to allow time for a full leadership election, which now involved party members too (a rule change dating from the 1980s), but with only token resistance, Mr Brown was made prime minister without consulting them.

Since then, things have only grown more complex for the Conservative Party as well, thanks entirely to the need to poll members, introduced by William Hague in 2001. When David Cameron announced his resignation immediately after the Brexit referendum, he might have ended up staying in office for weeks.

Instead, the field of candidates for his replacement was narrowed down to two, Theresa May and Andrea Leadsom, after just a single ballot. Mrs Leadsom then withdrew before the membership vote, shortening the timeline even further and leaving Mr Cameron’s transition at just two weeks and five days.

In 2019, however, ordinary members of a political party got to elect Britain’s prime minister for the first time ever. Unlike in 2017, 10 candidates declared and it took five full ballots across seven days to reach a final two of Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt and then a further month for the membership vote to take place.

The ostensible reason for Mr Johnson to cling to power until the Autumn is to allow the party time to choose a new leader and for that new PM to have a triumphant entry at the party conference in October.

It may be that the leadership contest takes several weeks, but it seems rather bizarre that Mr Johnson might try and stay in office beyond the end of that period, knowing that his party wants him out and that his successor has already been selected.