Brett Kavanaugh and the Private School Pecking Order

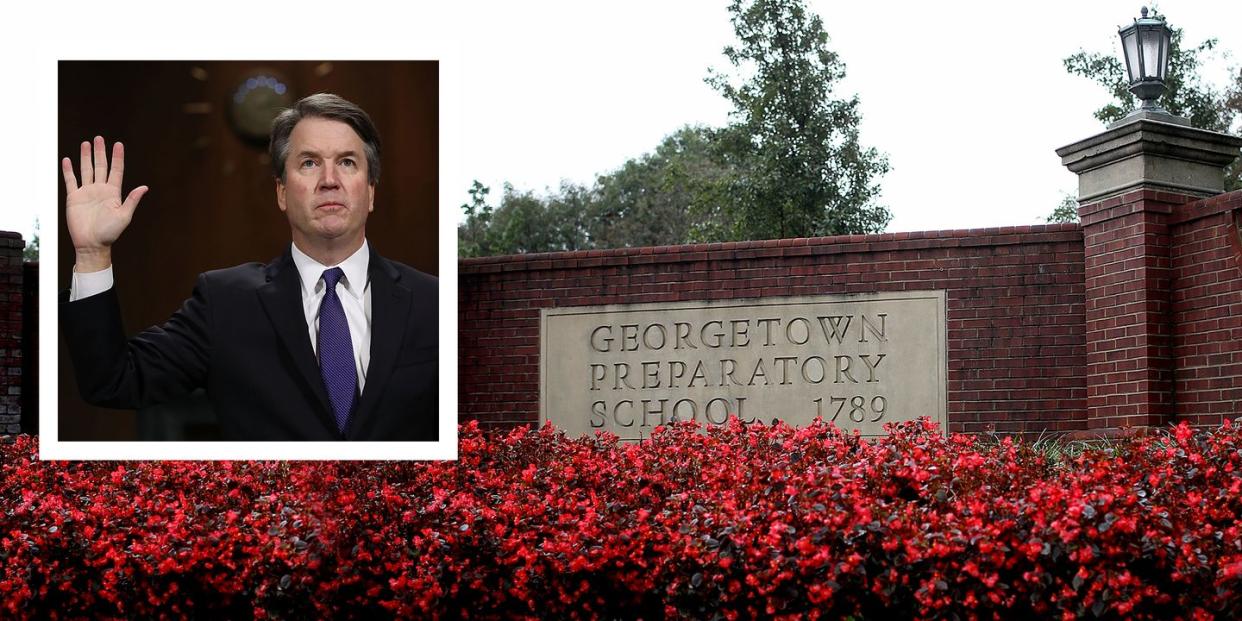

For most Americans, the fact that Donald Trump’s two Supreme Court nominees, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, both graduated from Georgetown Prep-a private, all-boys Catholic school in suburban Washington, D.C.-served as a surprising revelation about the smallness and insularity of our country’s ruling class. To those of us who attended a ritzy D.C. private school, however, Gorsuch’s and Kavanaugh’s shared alma mater came as a different kind of shock.

That a D.C. prep school would produce two Supreme Court Justices wasn’t terribly remarkable. Frankly, it was almost to be expected-at least by our parents. But that, of all the D.C. private schools, Georgetown Prep would be the one to have two graduates on the highest court in the land was something few of us could fathom.

Georgetown Prep is invariably described in national news stories as “elite,” and it is. From its 1789 founding to its nearly $60,000 annual tuition to the nine-hole golf course that doubles as the school’s front lawn, Prep has all the trappings and accouterments of an elite institution. But there are degrees of elite, and in the rarefied world of D.C. private education, Prep has long been viewed as a middling student at best, a problem child at worst-good on the football field, lousy in the classroom, wasted on the weekend.

If you wanted to find the D.C. private school most likely to be incubating future Supreme Court Justices-and Senators and even Presidents-you’d start at St. Albans, the all-boys Episcopal academy on the grounds of the National Cathedral; or its sister school, the National Cathedral School (NCS).

You’d scope out the coed Quaker school Sidwell Friends just a couple blocks up Wisconsin Avenue from St. Albans and NCS; or the all-girls school Holton-Arms in Bethesda, Maryland. You might even stop in at Georgetown Day School, which is sometimes confused with Georgetown Prep, at least by outsiders, but is in fact its polar opposite: It has female students and it doesn’t have a football team.

You’d visit these schools not only because they are where Washington’s power elite send their own children. The Obamas and the Clintons, not to mention Bob Woodward, have all been Sidwell parents; Al Gore chose St. Albans, his own alma mater, for his son and NCS for his daughters.

You’d look at these schools because, in Washington, they have the reputation for furnishing their students with the educations-and the connections-that enable them to eventually reach the pinnacle of American politics.

I don’t mention this to boast, since I didn’t attend any of these schools. Instead, I went to Landon, which, like Georgetown Prep, is a D.C. all-boys school with a reputation for being more of an athletic powerhouse than an academic one. While the parents at Sidwell or NCS tended to be old money or worked for high-powered law firms or as prominent doctors, the stereotypical Landon parent was a wealthy suburban real estate developer.

I had the occasional Senator’s or Congressman’s son as a classmate, but the suspicion was always that they were at Landon because they didn’t have the test scores to get into St. Albans. And while Landon had many phenomenal teachers, and the top students in each class did typically go on to the Ivies or one of the top liberal arts colleges, my classmates tended to be better at football and lacrosse (and keg stands) than chemistry or calculus. Indeed, when we would play-and, usually, whoop-St. Albans or Sidwell in basketball, their students would tauntingly chant at us: “SATs! SATs!”

And yet, at Landon, we still looked down our noses at Georgetown Prep. Not as much as we looked down at, say, Bullis-whose school colors, we used to joke, were "dumb and gold"-but we viewed the Prep boys as even bigger meatheads than we were. When we faced off in basketball, Landon students would taunt our Prep counterparts with chants of “Teabag!”-a reference to a rumored (and notorious) hazing ritual at the school.

Which is why the picture of Kavanaugh as a hard-drinking, hard-partying, boorish high-school student is so recognizable to those of us in the D.C. private school community. Although I graduated from Landon in 1992, a decade after Kavanaugh was a student at Prep, the hallmarks of his teenage years-the keg parties, the yearbook inside jokes, Beach Week-were all still very much the norm for my own.

It’s also why the picture of Kavanaugh at his confirmation hearings-his anger, his narcissism, his solipsism-was so familiar to us, as well. If you grow up in the elite world of D.C. private schools, you don’t necessarily outgrow the pathologies you acquired in your upbringing.

A few years ago, Landon invited me to give its annual ethics lecture. When I was a student, the speaker was typically a politician or a successful businessman, who’d talk about leadership. As a journalist, that wasn’t a topic on which I had much to offer, so I decided to talk about the importance of empathy, both professionally and personally.

Landon had recently been through a trying time. A group of freshmen were exposed, by The New York Times’s Maureen Dowd, for having invented a fantasy-football-like game by which they’d draft girls and then accumulate points based on how far they got sexually with each one. (At the time, a Landon rep said, “Landon has an extensive ethics and character education program which includes as its key tenets respect and honesty. Civility toward women is definitely part of that education program.”)”

Worst of all, a recent graduate named George Huguely, a lacrosse player at the University of Virginia, had been charged with murdering his former girlfriend- a true-crime story that wound up on the cover of People. In 2012, he'd be found guilty of grand larceny and second-degree murder.

In my lecture, I talked about how putting myself in the shoes of the people I wrote about made me a better journalist and how putting myself in the shoes of the people I knew made me a better person. I made an oblique reference to the troubles Landon had been experiencing and noted that I didn’t remember Landon being the most empathetic place when I was a student but that if the school was going to overcome its problems, then a little more empathy might go a long way.

As I spoke, I noticed a lot of yawns and eye-rolls from the students, and who could blame them? I’d once sat in those same seats, yawning and rolling my eyes, too. One speech from an alum wasn’t going to change the place or its pathologies. I finished my remarks and prepared to leave.

But then, an audience member rushed up to me. He’d gone to Landon himself, then to an Ivy League college. “I am so glad you talked about the importance of empathy,” he told me, shaking my hand and telling me how meaningful my speech had been. I smiled and thought for a moment that maybe my message had been heard, maybe things could change.

Then the man continued. “I’ve been going down to Charlottesville to visit with George in jail while he waits for his trial,” he said, “and no one understands what he’s been going through.”

('You Might Also Like',)