Doug Emhoff: A Husband and a (Second) Gentleman

On the eve of Election Day 2024, we're resharing this story about Kamala Harris's relationship with her husband, Doug Emhoff, from 2021.

In the lead-up to the 2016 election, former president (and, at that moment, aspiring first gentleman) Bill Clinton trotted out a stump speech line at an event for his wife, telling reporters, “I am tired of the stranglehold that women have had on the job of presidential spouse.” Four years later, when presidential candidate Joe Biden promised to pick a woman as his vice president—and to bean-count his cabinet to ensure that it met a level of racial and gender diversity that reflected America itself—he perhaps did not think of the trailblazing first he might be furnishing by proxy: a male vice presidential spouse. With his appointment of Kamala Harris as running mate, a Magritte-style defamiliarization of the familiar took place, as the most traditional image in American politics—a blue-suited, brown-haired white man—suddenly reconstituted itself as a radical one, and Harris’s husband, Douglas Emhoff, a Los Angeles entertainment lawyer in his mid-fifties, whom she married in 2014, suddenly became, as second gentleman–elect, something of a sensation. (He is also the first Jewish spouse of a president or VP.) There was no doubt that Kamala Harris burst through barriers as the first woman and first woman of color to be elected VP; news outlets described how Emhoff was also poised to break stereotypes and make history.

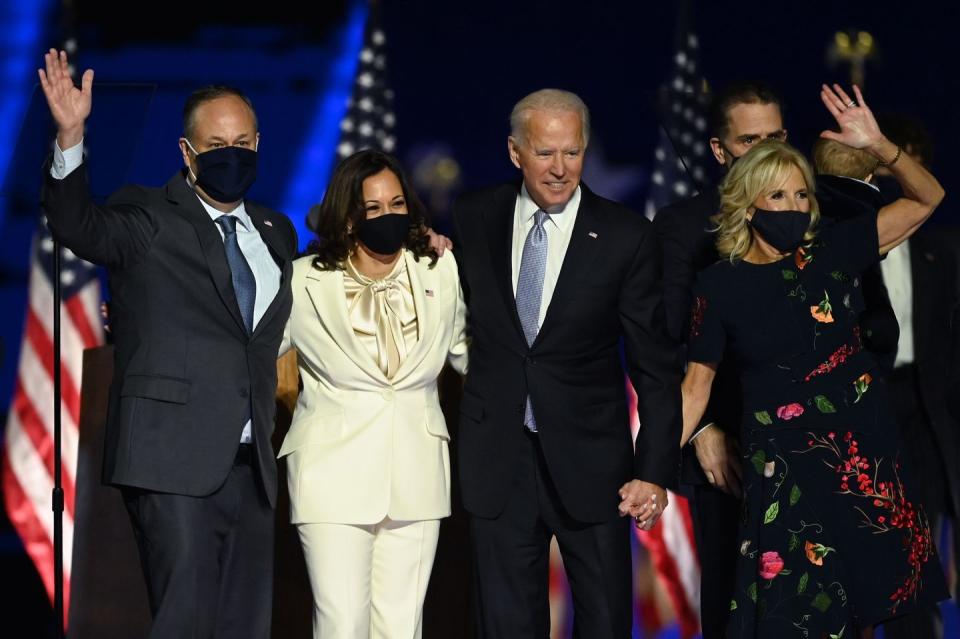

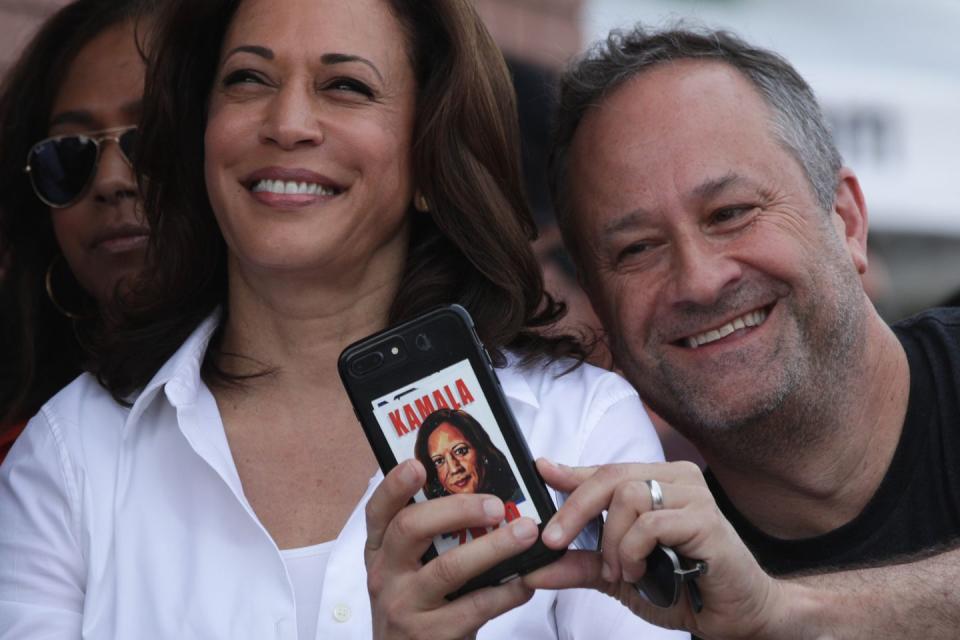

We won’t know until after the inauguration how, precisely, Emhoff will inhabit the office of vice presidential spouse—there isn’t really a playbook—but he is floating for now on a cloud of popular goodwill and general benevolence. He sprang, literally, onto the national stage when he snatched a microphone out of the hands of a protester who had stormed the podium and aggressively grabbed it from Harris. This was just one endearing and admirable image of Emhoff, and it stands in stark contrast to the public image of the outgoing administration, in which Donald Trump has difficulty even holding hands with Melania without slapstick comedy–style gaffes, and our understanding of VP Mike Pence’s marriage is that Pence won’t eat alone with a woman other than Mrs. Pence, whom he reportedly calls “Mother.” The media gushed over photos of Emhoff bear-hugging Kamala that he posted on Instagram; the couple suddenly made an ordinary act glamorous, such was the contrast with the excruciating, cringey romantic iconography of the past four years. After Harris and Biden won the election, a slew of articles about Emhoff came out, praising him for putting his career on hold to help Harris. #DougHive, a hashtag for his unofficial fan club, was used more than 6,000 times; originally a spin-off of Harris’s #KHive, Emhoff’s supporters took on a life of their own. They seemed to be saying that everyone wants a Doug of their own: kind, emotive, present.

In the lead-up to the election, pro-Trump groups seized on a video in which Biden called Emhoff “Kamala’s wife.” It was a flub made in earnest, but it succinctly encapsulated how Emhoff has defined and distinguished himself in the past few months: as a support system whose public role is to love Harris and whose career and desires are, and ought to be, subservient to her ascent to power—historically, of course, a wifely function. During the campaign, he crisscrossed the country as a campaign surrogate; just after Biden and Harris won the election, he announced that he’d leave his job as a partner at the law firm DLA Piper. Their successful marriage became almost a stand-alone character, in which instead of the lovely wife next to the politician husband, there was Doug, unflappable, by Kamala’s side. “The thing most people come away from him knowing is just how much he loves his wife,” says Chasten Buttigieg (husband of Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg), who spent time with Emhoff during the Democratic primaries. “How excited he is to support his wife. How really willing he has been to step away from his career and follow in VP Harris’s footsteps.”

The supportive, loving male is a delicate position to occupy in contemporary American society. It’s certainly politically advantageous these days to identify oneself as respectful to women, but like many public-facing Great Marriages and presentations of functional domestic life, the posture can read, even if earnest and authentic, as slightly automaton. (“We sometimes joke that our modern family is almost a little too functional,” Harris wrote in a 2019 personal essay in Elle about being a stepmother.) There is Emhoff in a People magazine video, nodding solemnly and silently as Harris describes cooking meals ahead of time and combating racism; Harris, in a Zoom interview, quips that Emhoff is “really trainable” when it comes to cleaning. On another Zoom chat he talks about assembling for her “one of those 5,000-piece bikes” when the gym in their DC apartment building shut down due to Covid. “She was very proud of me for that,” he says. His ear was pressed to the door when Harris took the call from Biden asking her to be his running mate. (Both Emhoff and Harris declined to comment directly for this story.)

It all reads very Mr. Nice Guy Goes to Washington—and it’s working. The image the couple cultivates seems compelling to large swaths of the electorate. Alex Weingarten, a friend and former colleague of Emhoff’s at the Venable law firm, says, “There’s really been a reaction to a man being supportive and loving to his successful wife.” And it goes beyond gender—their relationship is practically the tangible iteration of the intersectionality so many seek in today’s politics. We claim to want political leaders to espouse certain values, and here, in one multiracial, half-Jewish couple, is a rewrite of ideas about stepmothers, standoffish men who won’t commit, divorced parents, mixed identities, strong women, power couples—all of it.

“Let’s just pause for a moment and say: This is really something. It’s layer upon layer upon layer,” Nell Irvin Painter, professor emerita at Princeton University (known for her book The History of White People), tells me. “The United States of America, in which we are still talking about segregation and discrimination and sexism and #MeToo, where all of this is still in our society, and here is something that takes a step—not just a sidestep, but a step forward.” She goes on: “I think there really is something to the iconography of power, how it looks.”

The iconography of the couple is perhaps more important than ever now, and takes on both a new luster and a new gravity, as a woman of color and a Jewish man ascend to power just days after the seat of government was stormed by throngs sporting "Camp Auschwitz" hoodies and brandishing Confederate flags. Emhoff and Harris watched "in horror" as the Capitol was taken over on January 6. "It was an exposure of the vulnerability of our democracy," Harris, who was taken to a secure location with Emhoff, said. Nell Irvin Painter told me: "Considering the white nationalism of so many of the rioters and the historical animus of white nationalists against what they call 'race mixing,' Emhoff/Harris are likely targets of mob violence."

Harris and Emhoff are determined and resolute in the face of these new events. Of the diversity he and Harris represent, Emhoff told CBS: "It reflects America. And that's what it should be. It should just be about love and unity." In a separate interview after the mob attack, at a private fundraiser, he said that "with every day, the transparent sense of responsibility has continued to grow. We're also going to be showing the nation and the entire world that we are ushering in a new chapter, one of healing, of coming together, and of an America united."

Emhoff and Harris were set up in 2013 by Harris’s close friend Chrisette Hudlin, whose husband Reginald produced Django Unchained. Emhoff frequently rolls out the story of their blind date: how awkwardly earnest and rambling his initial voicemail to Harris was (they play it each year on their anniversary); how forward he was in the email he sent the morning after their first date: “I want to see if we can make this work,” he told her right away, efficiently attaching a list of all his available dates over the next few months. It has become a component of their narrative packaging, as has Emhoff’s relationship with his ex-wife Kerstin, with whom he has two children in their twenties. It is staggeringly and almost unconventionally amicable: The children, Cole and Ella (named for John Coltrane and Ella Fitzgerald—Emhoff is a jazz enthusiast), call Harris “Momala”; Momala timed her travel so she could attend Ella’s swim meets; Kerstin Emhoff even helped on Harris’s initial run for president.

The script of Emhoff’s professional life prior to his leaving DLA Piper to assist in the Biden/Harris campaign moves briskly. He started his career as an entertainment lawyer at Pillsbury Winthrop, in Los Angeles. In 2000 he launched his own boutique firm and sold it in 2006 to Venable, where he worked until he became a partner in the Los Angeles office of DLA Piper. (Emhoff and Harris now share a $5 million home in Brentwood and apartments in Washington, DC, and San Francisco.) Emhoff’s clients have included the husband of a Real Housewife of Beverly Hills, the arms dealer Dolarian Capital, and the Taco Bell chihuahua mascot, in addition to mainstay corporate giants like Merck and Walmart. A New York Times piece from September 2020 notes that among those he has represented at DLA Piper are “a slew of clients that run afoul of liberal sensibilities.” The announcement, just after the election, that he would be leaving the firm, which has also lobbied on behalf of Bahrain and Afghanistan, may have been rooted less in a desire to be there fully for his wife than in the necessity of doing a pre–Biden administration distancing act from any potential conflict-of-interest complications. (In a similar vein, Emhoff divested individual stock holdings that could be targeted by Harris’s critics as possible conflicts.)

Weingarten, Emhoff’s former Venable colleague, cites his friend’s “team-building” abilities, and says that “he views himself as the ultimate utility player.” Weingarten is talking about lawyering skills, but those skills have already translated to fundraising and networking for the Biden/Harris campaign, in both L.A. and Washington. When Harris ran for Senate in 2016, two years after their wedding, a large percentage of her campaign donations came from Emhoff’s law connections; during her run for the presidency, Emhoff became her liaison for fundraising in the legal community.

This genre of support is among his very powerful political attributes. Greg Schultz, Biden’s general election strategic adviser, says that Emhoff was “sent all the time to probably the hardest spots,” deployed as a multipurpose cheerleader who could refract whatever the moment called for, instead of leaning into his own identity. “Doug has enough street cred that you can send him to the upper Midwest, you can send him to the industrial heartland, you can send him to a farm, even send him to a Black community, Latino community, and he can resonate.” (As Cole Emhoff said to the New York Times about is father, "I think Doug is a bit of a chameleon, and that's why everyone loves him.") Emhoff, who grew up in New Jersey, managed to evoke an emotional response when he personally called field organizers in Michigan and North Carolina in late September to thank them for their efforts. “So here I am crying on a beautiful Tuesday afternoon bc a half hour ago @DouglasEmhoff called me and thanked me for helping to flip Michigan blue this year, and that is the motivation I needed,” was one of several dewy-eyed tweets in response to Emhoff.

It is not surprising that an unnamed source told the New Yorker that when Harris married Emhoff, the source became certain that Harris intended to run for president. After all, in America politicians at the top of the ticket are expected not to be single, and though it would be unfair to say that Harris aptly divined how politically useful Emhoff might be, his adaptability and his ability to shmooze did end up making their relationship very sellable on the national stage. Harris knew she couldn’t win without a man by her side; Emhoff suits this precarious position. The way he presented himself throughout the campaign was inextricably linked to his adoration for Harris. A pool report from a summit with Jewish mayors in which Emhoff participated reads, “He was typically low-key until he got to the part when he talked about electing Joe Biden president and ‘my wife Kamala Harris, vice president,’ punching that last part with raised voice and a big smile. ‘I just love saying that,’ he said.”

At a Zoom campaign fundraiser event with David Letterman in October, Emhoff, looking slightly into the future, expressed an interest in doing pro bono legal work when Harris assumes office. He has mentioned a vague desire to focus on access to justice—and, more recently, food insecurity. (Though his plans for his tenure as second gentleman remain unformed, he is slated to teach a course on entertainment law disputes at Georgetown Law Center this spring.) And yet the brunt of his public presentation is, in his words, this: “I’m her husband. That’s it. I’m her partner. I’m her best friend. I’m here to have her back.”

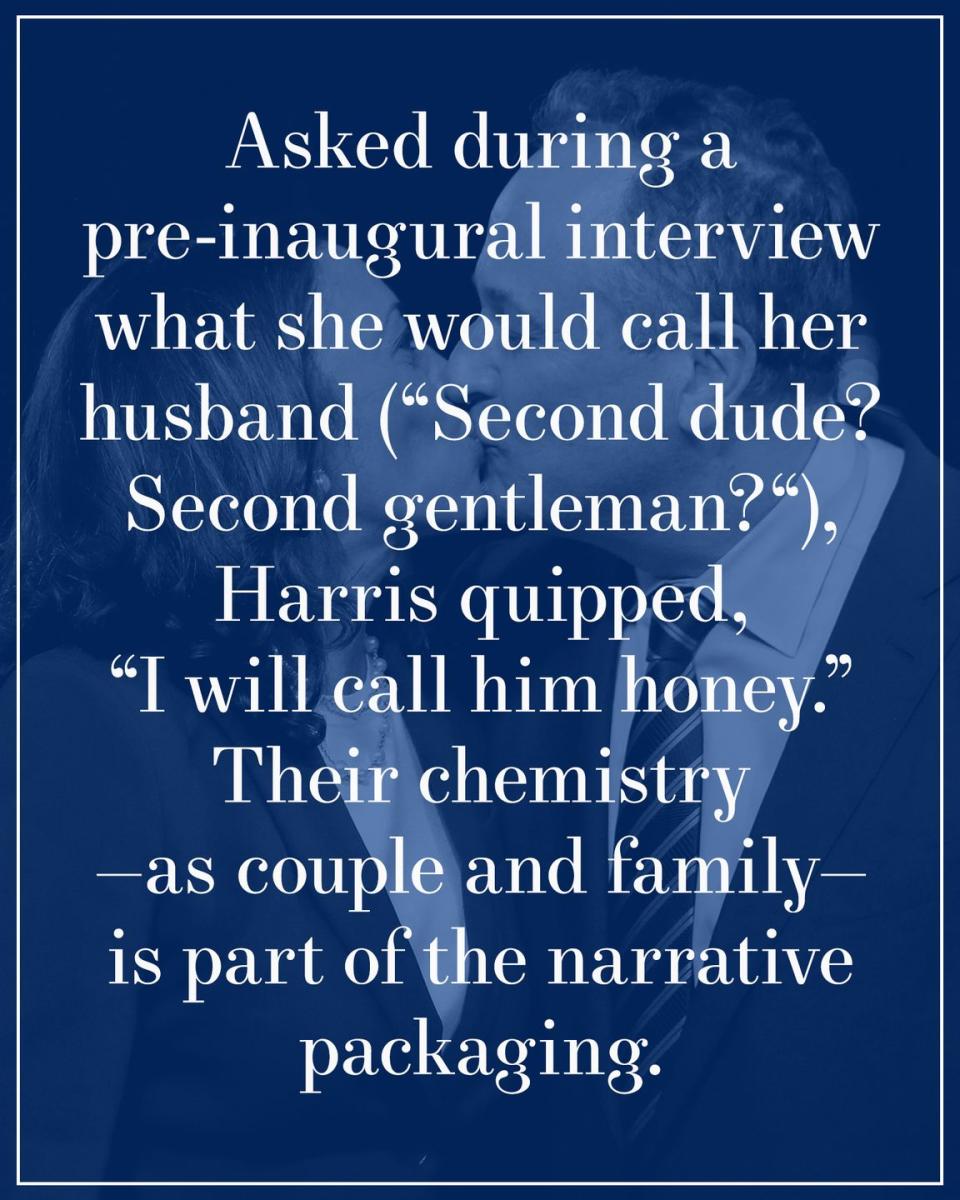

The evolving role of the second lady, a position with contours that have long been amorphous, now becomes more so as America ushers in Emhoff as the first second gentleman. The title itself is new. When Harris was asked about the terminology by Jake Tapper in a December CNN interview (“Second dude? Second gentleman?” The latter is the official term), she said, “I will call him honey.” Even before Emhoff, there was no playbook for being married to the vice president. “The first lady’s role isn’t official or statutorily codified anywhere. Go down to the second lady and it’s even less so,” says Anita McBride, who served as Laura Bush’s chief of staff. “We knew this day would be coming. Every person who comes into the role of the spouse gets to pick and choose—they get to establish a new precedent. Heretofore, Emhoff’s role has been a very traditional one. His priority was his wife’s success.”

So far, he is not so much carving a new space as upholding traditions that might feel dated if a woman embraced them. In fact, giving up a career is something of a rarity among Emhoff’s recent predecessors. Dr. Jill Biden taught full-time at a community college while serving as second lady during the Obama administration. Lynne Cheney, a historian, wrote six history books for children and was a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. (Joan Didion’s famous essay on Dick Cheney credits Lynne’s perseverance for Dick’s entire career—a spousal dynamic that Emhoff has very much distanced himself from, as a function not only of his and Harris’s ages when they met but of his natural disposition.) Tipper Gore was a crusader against the music industry’s offensive lyrics. Second ladies—and it’s quite a prerogative—can use their platform and the powerful connections that come with it to support their interests. “It’s not solely a social role,” McBride points out. Of Emhoff’s decision thus far to cast himself as supportive, she says, “If somebody wants to play a traditional spouse role, isn’t that the whole point of choice?”

However Emhoff is positioning himself now, one would have to be somewhat credulous to think that the fabric of his daily life will consist purely of enacting this “supportive husband” work once his wife is in government. “In many ways I think it’s very smart for the spouse to make people believe—as Nancy Reagan did—that they’re just there for support,” says Kate Andersen Brower, author and historian of vice presidents and first ladies, “and then behind the scenes they’re doing all sorts of things.”

Emhoff will certainly take on some duties that historically had an association with women. For one, he will have the leadership role in the Senate Spouses Club (formerly known as the Senate Wives Club), which was formed in 1917 as a Red Cross support unit during World War I. Emhoff’s leadership duties in the club will include things like planning an annual luncheon for the first lady. “Until the 1980s it was known routinely as the wives club, but by the ’90s, when you start to get a lot of women senators, it changed,” says Betty Koed, assistant historian for the U.S. Senate. “For years Senate wives didn’t work. They came to Washington to support their husbands. But spouses now tend to maintain their own careers and keep their lives going.”

As John Bessler, Senator Amy Klobuchar’s husband, who got to know Emhoff in the club, told me, “When I arrived, you’d go to these lunches, and on a receipt to pay for your meal it would say, ‘Senate wives,’ because they hadn’t updated that.” Today there are many male lawyer spouses in the club, a clique that includes Elizabeth Warren’s husband Bruce Mann as well as Bessler and Emhoff. Brower adds, “The pendulum is swinging. We’ve come off four years of white male–dominated administration. So now we’re open and interested as a country in seeing diversity. That includes people of color, and also, who is it that’s doing these feminine roles?”

It is, of course, a significant precedent to have a man embracing tasks that have long been assigned to women. That fact alone makes it “a historic moment,” Koed says. “Nobody was expecting Bill to sit at Hillary’s side and serve tea,” says Brower, and “it matters if little boys in America grow up with a man who’s comfortable and secure enough to do that.”

Dr. Biden earned her degrees through hard work and pure grit. She is an inspiration to me, to her students, and to Americans across this country. This story would never have been written about a man. pic.twitter.com/mverJiOsxC

— Doug Emhoff (@DouglasEmhoff) December 12, 2020

What we know of Emhoff so far is that he’s an adoring political spouse who revels in helping a woman rightfully praised for her ambition. Conversations about Emhoff often yield somewhat stultifying descriptions of how supportive he is and little else. From John Bessler: “Doug was very supportive on the campaign trail. He very frequently would wear the campaign T-shirt.” From Sheila Nix, who served as Jill Biden’s chief of staff: “He cares about being a supportive team player and the process. I think that’s why people are kind of excited about it: because it’s like they know Doug, right? They know somebody like Doug.” Or Nell Irvin Painter: “We can just stand back and clap our hands. We should pause and be grateful for a man who says, ‘My job is to support my wife.’ ”

There are those who find Emhoff on a pedestal galling. “Everyone is applauding his decision to do something that women have done forever,” Brower says. “It’s kind of infuriating.” Emhoff himself is aware of the paradox at play. After an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal in December called on Jill Biden to drop the “Dr.” from her name, Emhoff tweeted, “This story would never have been written about a man.” And his position may well evolve into a high-powered role; we don’t yet know.

Regardless, in this moment Emhoff does feel like a radical character. “We still live in a pretty sexist country,” says Chasten Buttigieg. “The idea that it’s okay if women set aside their careers and ambitions because their men have dreams and goals, but for a man to do it is surprising—I hope that’s shifting.” After all, “this is not the only successful married couple in the country,” as Anita McBride puts it. Perhaps it is Emhoff’s “job,” Weingarten says, “to show the world how perfectly normal this is.”

Not everyone is yet on board with this contemporary, progressive iteration of masculinity, so deeply nontoxic. As Painter said to me, “Don’t forget there’s a whole world out there, call it Trump country, call it upstate New York, in which being a supportive man is not necessarily seen as a great role model.” And this is true for other facets he’ll help to usher in. Painter recalls friends of hers complaining about how big airport banners advertising Black History Month commercialized the month of recognition. “I see it as becoming American mainstream, because that’s what we do. How we become American is to be commercialized.” She drew a parallel to seeing a multiracial couple like Emhoff and Harris on the national stage. “How we become American is to be seen.”

Still, Emhoff’s stance as a chipper, willing, even fawning spouse can sometimes feel cloying. At moments it seems almost retrograde, as when People asked him about being a “protective white husband of a wife of color.” Yet Emhoff appears to be—blandly, amazingly—basically a good guy. So much so that it can be thrilling. Perhaps before he more fully defines the role of second gentleman, he is already doing something more significant: redefining for America what it means to be a member of that much maligned category, the older white male, and recasting it as part of the lineage of progress.

“So let’s appreciate it,” Painter says. “And then afterward, maybe we can go on and say, ‘Well, how about the next time we have a vice president who’s a woman who’s married to another woman. Or a vice president of any gender who really has some power to raise the minimum wage.’ We can go on to something else like that.”

But for now, America, meet Doug.

A version of this story appears in the February 2021 issue of Town & Country.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like