Dries Van Noten on a Life of Fashion, and What Comes Next: “I Loved It, and I Still Love It”

Photographed by Sam Hellmann

Approximately 36 hours after Dries Van Noten waved goodbye at the closing of his last-ever runway show, the legendary Belgian fashion designer is sitting in his sunny showroom in Paris. It’s another Monday morning at the office, with chicly dressed employees clacking away at computers. Wearing his signature navy jumper with khakis and tan leather shoes, the 66-year-old is brisk and well-rested. “I slept last night, which was not the case the nights before,” he says with a smile.

As we settle in for a wide-ranging discussion about his menswear legacy, his thoughts about the fashion industry, and his future plans, Van Noten starts telling me, almost by reflex, about how he had to split the footwear collection that lines the shelves around us into two parts, something to do with their Italian footwear supplier. “I have to say,” I tell him, “you don’t seem very retired yet.”

Van Noten made headlines earlier this year when he announced his decision to step back from the day-to-day grind of designing four runway collections a year. In this profession, designers don’t tend to know when or how to make a graceful exit. But the clear-sighted Van Noten has always done things on his own terms.

His grand finale took place in front of 800-plus friends, fans, customers, admirers, and peers, including several fellow members of the Antwerp Six, the group of Belgian fashion designers who graduated from the Antwerp Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1981 and proceeded to take the industry by storm. (The crew of longtime friends includes Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, Dirk Van Saene, Walter Van Beirendonck, Dirk Bikkembergs, and Marina Yee. Martin Margiela is often considered the seventh member.)

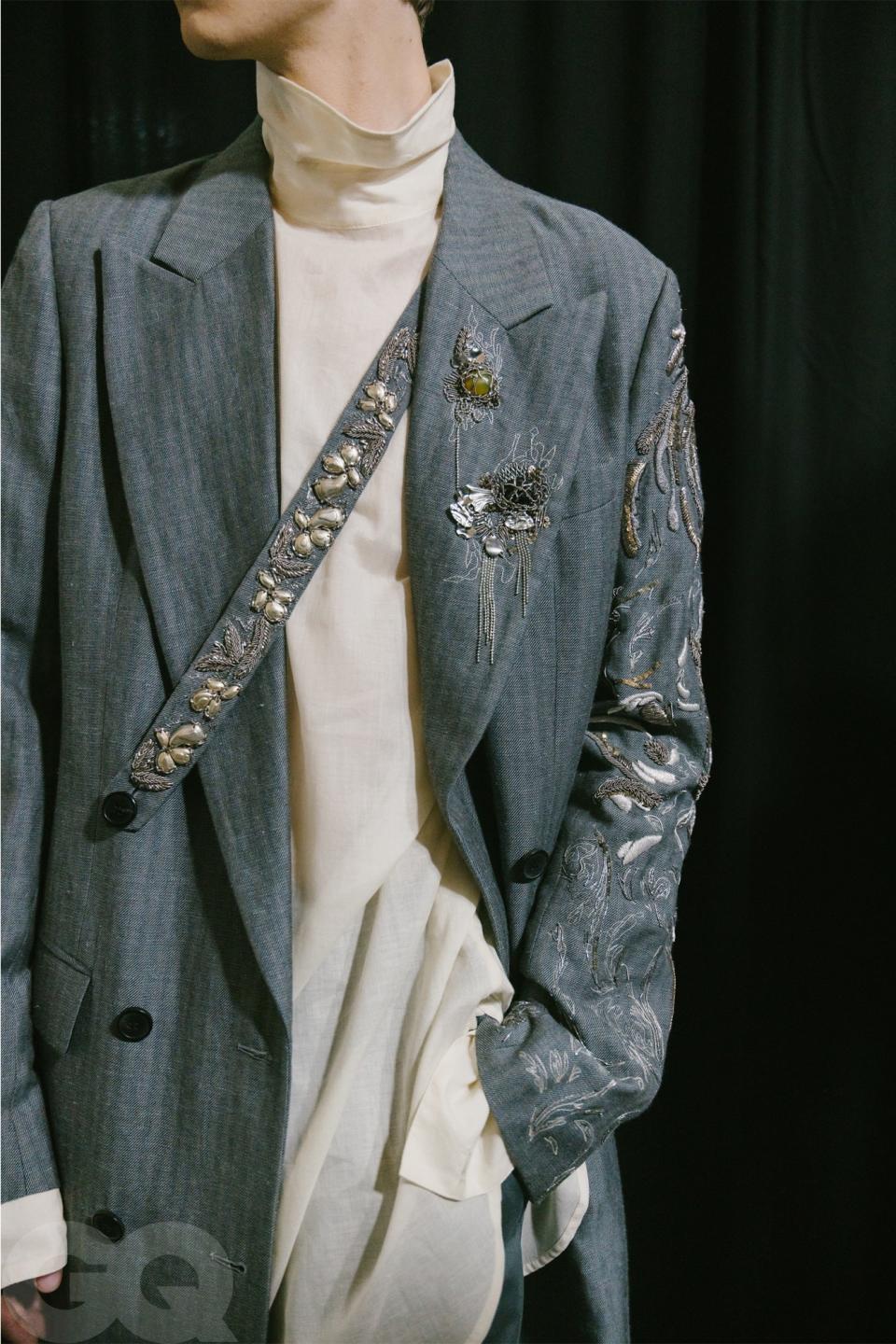

In classic Dries fashion, the show was full of clothes designed to make you the most interesting person in the room, intelligent in cut and artful in color, pattern, and texture. But it was not a retrospective of greatest hits, though the cast included several gray-haired former Dries Van Noten mainstays. Backstage after his bow, a clearly overwhelmed Van Noten couldn’t help but gush about the new materials (like crunchy recycled polyesters) he juxtaposed with classic English wools, and in our conversation his eyes glint when he mentions the ancient Japanese printmaking technique he utilized for the first time to create a garden of beautifully muted floral trenches, trousers, and tops. It was a tender offering to the fans who have made his work a part of their daily lives, and a clear message to the as-yet-unnamed successor who will build on his legacy. “They have to dare, they have to move forward,” he tells me. Following the show and an endless number of backstage hugs and selfies, Van Noten danced under disco ball lights until well after midnight.

The next phase of Dries Van Noten’s life will officially start when he returns to Antwerp, before embarking on an eight-day vacation to the Amalfi Coast with his partner, Patrick Vangheluwe, and their dog. As he dispenses with the small talk, I can tell that the designer is eager to go home. But I also sense that he’s not exactly leaving this all behind. “I still have a lot of plans, I'm still going to do different things,” he says in his clipped Flemish accent. “The fashion world and everything, it's my soul, it's my life. So it would be strange to now close the doors completely. So, I won't.”

GQ: In the lead-up to the show on Saturday night, you disclosed in a few interviews an uncertainty about your decision to retire. How are you feeling right now?

Dries Van Noten: I'm happy. I think next week when it really starts to sink in, I am going to have moments that I say, “Well, my goodness, what did I do?” I think it's normal when you do something with your heart and your soul, in such a passionate and complete way as I did. I was always thinking about fashion. Everything that I looked at was a source of inspiration. I was really feeding my creativity constantly.

We live in the countryside, so every day I spent one hour and a half in the car. I would hear something on the radio and quickly Shazam it if it was interesting. That's going to be strange that I don't have to Shazam music! When I go to an art exhibition, I take a quick picture of an interesting color combination—maybe that can be something. Now, I can look just for the pleasure of looking, and not looking to find inspiration. It will be more about looking to understand, to understand the why and the how and everything. So it’s going to be a different life, but I will still continue working on the company’s beauty and perfume, which I love to do, and I will also continue with store design and all those things. And I will advise on the men’s and women’s collection. Of course, the thing is they can follow my advice, or they can not follow my advice.

There's so much to talk about from the show, but I was struck in particular by the very last look, a long black coat with satin pockets, really fluid golden-silver trousers, and simple sandals. It was concise and poetic. Did you put a lot of pressure on yourself to end this show on a specific note?

I would lie if I said that it was an easy one. Of course, the pressure was on. Expectations were really high. I have to say, I was quite surprised about the intensity of the reactions when I announced [my retirement]. I thought, Okay, of course people are going to react. But the emotional avalanche was really something which I didn't see coming. Originally we said, "Okay, we're going to do just a normal show." I knew that I wanted to finish with men's as I started with men's. I wanted a bookend.

But I started to hesitate on my idea of doing a normal show. A lot of people wanted to attend. So I said, “Let's go for it.” And then creatively, I didn't want to do a best-of collection. I didn't want to do what people would expect: lots of colors, lots of prints, lots of embroideries. I wanted to do all those things, but in a different way. It was my last chance to take risks. So I wanted to try new materials, new printing techniques, like a Japanese system called suminagashi that has existed for a thousand years.

It was challenging. The final edit was difficult, because originally we wanted to end on a gold blazer, but I thought it was too in your face. And I love the idea that we started the show with Alain Gossuin wearing a long coat in a beautiful quality wool-linen. Alain opened our first show in 1991. I thought it was important to show the final look on a young guy for whom it’s his first season walking for us, a guy who could become the future Alain. Alain did 34 shows for us, and the young guy was so stunning in the way that he walked and the way he was wearing the coat. I said, “That has to be the end of the show.”

You’ve never been one to leverage your personal celebrity. And then you announced your retirement and the spotlight has been squarely on you ever since. That must have been a strange feeling.

Quite strongly, yes. But I'm really happy. After the announcement, I received so many handwritten letters, and not only from old people, but from young people, from colleague designers. They took the effort to send me a letter where they shared their emotions, how the clothes I made were meaningful to them. And the designers told me that I was inspirational to them, that the independent way that I worked pushed them to take steps, to help them make decisions. All those things. And it continues. Three steps out of the door this morning, a person who I don't know was like, "Dries, thank you for what you did for fashion. Bye." And jumped in the car and disappeared.

I understand you’re going home to Antwerp tomorrow, and then to Italy for a week of vacation before getting back to work on your next plans. What else can you tell me about those plans?

Our plans are not completely concrete yet because I haven’t had time really to work them out. But besides what I'm still going to do for the company, I have a lot of other ideas of things involving young people, because this I want to continue. What is really important for me is that I stay connected with young people. At the moment that I made the decision a year ago, I told Patrick, "Don't even think that I'm going to only spend time with people in their 60s and 70s. No, that’s not going to be my life." I want to have that constant back and forth of information and visions and things like that with young people around. Maybe I will mentor them sometimes, but I also want them to continue to teach me things.

So many young people find their way into fashion through your work. Part of that is due to the mystique around the Antwerp Six. Did you find that the reputation around the Antwerp Six helped you build your career, or did you feel like it was a box you had to get out of?

A few weeks ago, we were sitting together again, all six of us. It was to have a fun moment, but we were talking about how iconic the Antwerp Six became. It was never a marketing plan like, "Oh, let's form a group and do this." It just happened. We were showing at the British Designer Show in 1986 in London, tucked away on the second floor of a showroom behind wedding dresses and lingerie.

We knew that our names were very difficult to pronounce, so we made flyers that said "Come look at the six Belgian designers, the six from Antwerp upstairs." And then this term was picked up by Women’s Wear Daily in an article, and the group was formed. We were a bunch of friends and we shared the passion for fashion. We had all different visions of what fashion could be, but we shared a lot of information and pushed each other. And we are friends, so we're still going out together. Ann is an addicted gardener, so we share a lot. She grows tomato plants which she gives to me, and we grow plants which we give to her.

What else did you guys talk about?

Legacy and history, but of course also about families and things like that, children, grandchildren.

I'm curious about what your earliest memory of fashion is. Not clothing but fashion as a practice and a creative form.

For me, it was going to fashion school. I learned everything at fashion school. Before, I went to Jesuit school, which is of course very, very severe and very classic. And my parents had a fashion store, so I traveled to Florence and to Milan with them to see collections and everything. So I was really fascinated. But of course, being at the Jesuit school and discovering that you're gay, things like that didn’t really help. But going from Jesuit to fashion school, meeting people like Walter [Van Beirendonck] and Martin [Margiela], it was like, "Wow, there's a different world."

Of course, it was a super-exciting time for fashion itself. In ’74, ’75, you had Armani and Versace who changed menswear completely, with linen suits, leather jackets, logos, all those things. Immediately after you had [Claude] Montana and [Thierry] Mugler: big shoulders. So you went from elegance and casualness to power dressing in one year’s time.

And then you had punk, negativism, dark aggression, all those things. Music became screaming. From London you had Vivienne Westwood, you had the New Romantics happening. After New Romantics, you had Japanese design. The first fashion show of Comme des Garçons [in Paris], which we went to in 1980. I’m talking about five years. Can you imagine what kind of firework of ideas and visions and different attitudes and things like that? So for us, fashion was incredible, and it was all related to things which were happening in the world.

You attended the first Comme des Garçons show in Paris?

Yeah.

What was that like?

Well, we were very good at cheating our way into fashion shows during school. Already we were copying invitations like crazy. We would get one invitation, and then one invitation became 12 invitations and everybody went. Also, [the late New York TImes photographer] Bill Cunningham really helped us very often into fashion shows. He would say, "Fashion shows are not for all those old people, they are for young people like you. You have to see the show." He would open the cords on the sides of the tents and we would slide in. Thank you, Bill Cunningham, for doing this.

Do you remember the first piece of clothing you ever made?

I never made clothes myself before fashion school. Of course, in fashion school, the first year is very theoretical. It's only from the second year on that you have to make clothes that have to be worn. The first thing I made was a men's blazer, a strange situation with a lot of elastics involved. So it was a strange time but quite fun. But what Walter was doing at fashion school, what Martin was doing at fashion school—their personality was already there.

How aware were you of the early buzz around the Antwerp Six? Did you process that 1986 debut as a life-changing moment?

It was a struggle. We were not prepared for it. I was lucky, because Barneys placed an important order. But of course the first years were really difficult. I was designing, I think, seven commercial collections for other brands just to earn the money to invest in my own brand. It was not easy. Martin was the first one who did his own show. Dirk Bikkembergs was the second one. I only had the money to start doing men’s shows in ’91. So it took a while.

Can you tell me how your spring 1996 men’s show in Florence went down? It’s still considered one of the most iconic shows not only of your career, but in men’s fashion history.

There was a disco ball! [Laughs.] We had the funding of Pitti Uomo, which normally had very official fashion shows. They hated us. We wanted to think a little bit out of the box. We said, "Okay, we're going to go to Florence, but we want to involve the people of Florence." So we had 140 models street cast from Florence and all over Europe. We really wanted to recreate a normal life on the piazza with the Italian lovers with the guitar trying to seduce girls. We had all of these things. We had people selling fake bags walking around between the models. And then during the show, we made a deal with two buses of Japanese tourists who walked through the show. It was really just chaos, but so much fun.

And then as a finale, we wanted to have fireworks. We talked with the guy who was responsible for fireworks in Florence, but we didn't know that he had done a big fireworks show the week before which was a complete disaster. Everything went wrong. So he had to prove to Florence that he could do good fireworks. We had a small budget, so we asked for 30 seconds of fireworks, and then at least we would go out with a big bang. We didn’t know that he delivered us fireworks for five minutes, which we shot in the air in 30 seconds. It was a huge explosion. It was such a bang that all the windows in Florence started to tremble, and all the car alarms and all the alarms of the museums went off. So the day after, [production designer] Etienne Russo was arrested! [Laughs.] He was arrested, stopped at the airport, and he had to go to explain what happened. It was a crazy thing.

Were there any other specific collections that stick out to you as a turning point in your men's business?

There are several. One which really sticks with me is [fall-winter 2011], the Bowie-inspired show at Musée Bourdelle. There are different shows where you see what we’ve learned. I once did a collection based on David Hockney [for spring-summer 2001], which is one of my worst menswear collections I ever did, I think. We tried to be more minimal, and it was clear that it was absolutely not for us. We tried to be cool and minimal in a way that was not good. But we learned from that very clearly, which resulted in a much stronger look.

You've spoken before about how around 2000 you underwent a radical shift in your thinking about making fashion. You decided that you had to focus on making beautiful clothing rather than trendy clothing. What pressures were you responding to at that time?

It was a strange time. It was all about Jil Sander and Helmut Lang. But we were still very successful with our business and had been growing really fast. And in the late ’90s, unfortunately my business partner Christine Mathys passed away. So from then I was responsible not just for the creative side, but also for the business side. And then we were approached by bigger groups. It was around when Alexander McQueen sold his business, Jil Sander sold her business, and young people were joining the big houses.

The conglomeration of fashion started.

You had Tom Ford starting to work at Gucci, with shoes and bags becoming clearly more important and clothes becoming less important. Everything was getting more about marketing. So it was really a time like, "Okay, who are we? Can we continue to do our clothes as we are?" In our team, I had a few people who said, "Oh, we have to get more minimal. We have to become more sharp." And that didn't really feel right.

That men's collection with David Hockney was sort of the moment I decided to go back to what I knew. But I also learned that I couldn’t do it too literally. So from then on you see that I started playing with contrasts and adding elements to the colors and embroideries to make my work more contemporary, to push it further.

Do you ever think about where you would be if you had sold the company to LVMH or the Gucci Group (now Kering) in the late ’90s?

Of course you think about it, and there was a lot of reflection when we became part of Puig. But I'm very happy. I could make fashion the way that I did, because that’s my love. I choose sequins, choose yarns, try mistakes, learn from mistakes. I loved it, and I still love it. That’s the thing that I’m going to miss. I don’t think I would be a happier person if my brand was 10 times the size and we had stores everywhere. That was not my goal. And now I know that I made the right decision.

Right, the garden's big enough.

Absolutely.

You've had a very interesting front row seat to the evolution of men’s style. How did you respond to the menswear revolutions over your career?

I think the moment that I started really to work on menswear was a revolution, especially the first years. The moment that we started to do men's shows, it became about a way of dressing. More about style than specifically clothes. When you analyze a little bit what was happening in the '80s, you had Italian designers who did great menswear really pushing things. But in the early '90s, from the New Romantics on, menswear became kind of womenswear in men’s sizes. I mean, you think about Montana and Mugler, they did exactly the same things for the guys for a girl.

And fashion became quite connected with gay culture, and of course gay guys are great clients for fashion. But the straight guys really disconnected. I think maybe that’s why Helmut Lang did such a great job, because he found a sense of strictness that was still something that lots of people could connect to.

I always was focused quite a lot on tailoring, and I really tried to push things in a subtle way. Okay, I did jackets with big shoulders and all those things also. But there was always kind of a realness there. It spoke to people because it was the things they liked to wear, but there was a subtlety there, I can say. There was a reality to it. And I think this is a fil rouge through my work.

Okay, I don't like where the fashion world is now, but one great thing is that you can dress head to toe in Versace and look cool and fashionable, and you can look great and cool in vintage, and you can look great and cool in Uniqlo. And that I think is great about fashion now I think. But of course what I like most is when you combine all those things together in a personal way. I see myself as somebody who creates words, but the customer has to make the sentences with it. It’s really your personality which creates the look, not my vision. I can give ideas, and it’s up to you to pick them up if you want.

Can you tell me more about what you don’t like about the fashion world right now?

Do you have the rest of the day to talk?

I’ll sit here as long as you want. It’s clear that right now fashion is in a very unsettled state, and the system feels more brittle than I think any of us realized.

But it's not fashion which is brittle, it's fashion business that is. And I think for me that those are two different things. Fashion is a desire. I think that's the power of fashion. You don't feel good, you put a sweater on and you feel much better. You want to shine at a certain moment, you can shine. You want to hide yourself, you can hide. And I think that's the power of clothes. I think that's what clothes are for. That for me is the important thing. It's what the businessmen made of fashion, that is a different thing. And that for me is not in the best condition at the moment. I think everybody knows that. How much fake desire can you create? Too much now, absolutely too much.

How much of your decision to retire was connected to these feelings about the industry?

Of course, it's part of it. But on the other hand, in difficult times we've been very successful as a brand. In difficult times people connected very strongly with the things we were doing. So I'm quite confident, and it's not because I say, "Okay, the fashion system is no longer working. I give up." That would actually stimulate me to continue.

In 2018 you sold a majority stake of your brand to Puig. Was that part of the planning for your eventual retirement?

That was really the idea. We were at a point in 2017 that I was approaching my 60s. And we were a very healthy company, but we had no e-comm business of our own. We had not enough stores. We had to start our business in China. So there were a lot of things. And our accessory business at that time was, I think, 4% of our turnover.

The first idea was that I would work until I turned 65 and then close the business. It’s over. But then I realized it would not be honest to my team in Antwerp. Some people have been with us for 25, 30, 35 years. They are starting families. It would be extremely incorrect to say, "I’ve had it. Financially, I don't need it anymore. Thank you. Bye-bye." So we first judged if we have enough identity that the house can continue beyond us. And we have a very good archive. I'm very proud of that. Our archive is organized. We have the patterns, we have fabrics and things like that. So there is material to work on. Not that I want them to make exact copies of what I did. But the future designers can use that type of thing.

So we found a partner in Puig and I made the decision to stop when I turned 65, but then COVID happened and I wasn’t ready yet. I hadn’t done everything that I wanted to do. But at a certain moment you have to decide and say: “It’s enough.”

What advice do you have for your successor, whoever that may be?

Dare. I think we always wanted to surprise people, and that's important. The last thing that I want is that they try to make a new version of what I was doing. I think they have to dare, they have to move forward. That's also why I did the last thing with the men’s show. I didn't want to do best-of. Okay, I took risks. Some people may be disappointed that it was not colorful enough or there weren’t enough prints, but it was exactly the way that I wanted it. It was the last chance for me to take risks, so I grabbed it.

Now that you’re stepping away, will you also move on from your uniform of navy sweaters?

[Laughs.] Well, the thinking is my whole day is making decisions. The last thing that I want when I open my closet is to decide. I want to have simplicity. When I go to restaurants, I have the dish of the day. I don’t want to open the menu and choose. Maybe now I'm going to experiment more with fashion. It's possible.

Originally Appeared on GQ