What The Health?! Ontario man's heart excavated from calcium shell

Can leftover spaghetti really kill you? Can you actually cough up a blood clot in the shape of your lung? In Yahoo Lifestyle Canada‘s newest series, What The Health?!, we ask doctors to weigh in on odd health news stories and set the record straight. Be sure to check back every Friday for the latest.

You’ve heard of a heart of stone and a heart of gold, but what about a heart of bone?

That’s in effect why a Hamilton, Ont. man recently required life-saving surgery.

Herve Ndikuriyo had been experiencing painful swelling in his legs for months, but attributed symptoms to long periods of standing at work. The discomfort, however, not only persisted after he left the job — it got worse.

Eventually, a chest exam revealed the cause of his pain: his heart had become encased in calcium.

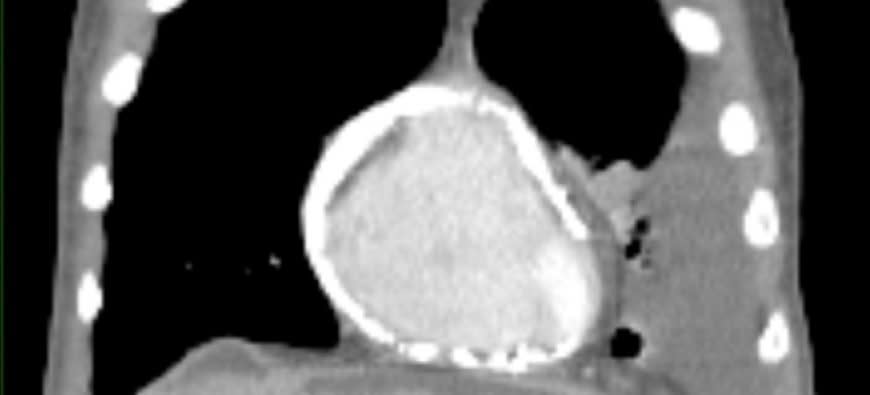

“On the CT scan, it looked like it was wrapped in bone,” Dr. Richard Whitlock, a heart surgeon at Hamilton Health Sciences, said in a news release.

Ndikuriyo was diagnosed with a rare condition called constrictive pericarditis, the inflammation of the lining surrounding the heart. His case was severe.

“You don’t normally see anything like that, ever, where he’s literally got a bone around his heart,” Vancouver cardiologist Eli Rosenberg told Yahoo Canada. “This is an extreme case.”

“The heart sits in a sac that’s fibrous, a bit elastic,” the CEO of Pulse Cardiac Centre, a multidisciplinary clinic with a supervised medical fitness and cardiac rehabilitation program. “In instances where that sac become scarred or loses elasticity, the heart is in a contained space. The heart needs to blow up like a balloon to fill up with blood and go up and down. If it’s in an enclosed space, it can’t fill with blood properly anymore.”

There are several causes of constrictive pericarditis. In the developing world, it’s typically an infectious problem, linked to viruses, such as hepatitis, or bacteria, like tuberculosis. In developed nations, it’s usually found in people who have had heart surgery or who have had radiation to the chest to treat breast or lung cancer or lymphoma.

It can also be a complication trauma (where there is damage to heart tissue) or chronic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, hypothyroidism, or kidney failure.

The prevalence of isn’t clear, though it is known to occur in 0.2 to 0.4 per cent of people who have had heart surgery.

What makes is tricky to diagnose is that symptoms can be attributed to so many other health problems. Signs include shortness of breath, fatigue (at first with exercise and then at rest), and swelling of the ankles.

“It mimics other things,” said Rosenberg, who has seen only two patients with the condition in his career.

Chest X-ray or electrocardiogram help make a diagnosis, although they may appear normal in early stages. An ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) would reveal fluid in the sac surrounding the heart, while the use of a needle to withdraw fluid can be done to detect bacterial infection.

n some cases, anti-inflammatories are enough to treat the constriction. In others, like Ndikuriyo’s, where the calcium had begun to grow into the heart muscle, surgery to strip away the shell is the only option.

Ndikuriyo, who came to Canada from Burundi as a refugee in 2013, was in surgery for about three hours. He was placed on a heart and lung machine while Whitlock carefully removed each tiny calcium fragment without damaging the heart muscle itself.

“This was the toughest case of this I’ve done,” Whitlock said. “It was very challenging to get everything freed up, but we did.”

Ndikuriyo is recovering well and has said he hopes to pursue a career in health care.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA!

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Check out Yahoo Canada’s podcast, Make It Reign — our hot takes on all things royals in a non-stuffy way — on Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts.