Hold the elevator: how Muzak became inexplicably hip

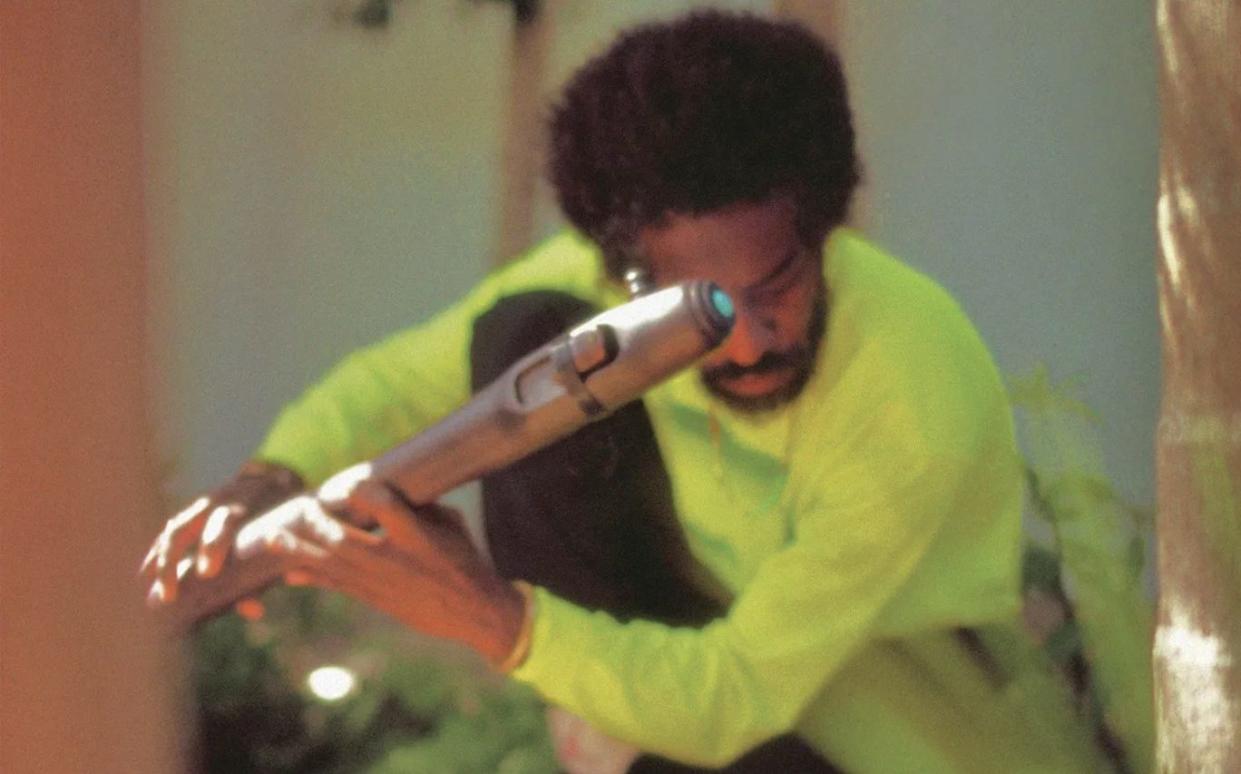

The flute hurts. At least it does for fans of rapper André 3000, who, as one half of Outkast, lit up the charts with early-noughties hits such as Ms. Jackson and Hey Ya! But that was a long time ago, and the musician, real name André Lauren Benjamin, has recently swerved in an entirely different direction with a collection of flute-based mood music, New Blue Sun. The response of many Outkast fans has been: hey…what?

There is no rapping on New Blue Sun. There isn’t even any singing. The record is a laid-back hodge-podge of ambient soundscapes, inspired by Andre’s friendship with jazz percussionist Carlos Niño. Blissed-out jams abound. Songs have names such as Ghandi, Dalai Lama, Your Lord & Savior J.C. / Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, and John Wayne Gacy. There is speculation that if you say that title three times, staring into a mirror, Benjamin will appear behind you, tooting his flute.

Some Outkast followers have not unreasonably wondered if André has taken leave of his senses. “André 3000 is probably gone for good,” lamented one on Reddit. “People should just rap over the André 3000 album,” suggested another.

But might they, in fact, be talking a load of rap? Rather than going out on a limb, perhaps André 3000 is ahead of the curve. Consider the current popularity of background music – which has quietly blossomed into a huge and lucrative genre. Spotify and other streamers brim with mood-affirming playlists. Spotify’s nine-hour “Chill Hits” playlist, for instance, has 5.4 million listeners.

Elsewhere, the ambient YouTube channel LoFi GIRL, which spins chill-out tunes 24 hours a day, boasts 16 million subscribers. These hazy vibes have even spread to hip-hop in the form of “SoundCloud rap” – a genre characterised by a woozy vocal style.

These trends didn’t materialise overnight. Background music has a history almost as long as the record industry itself. “Muzak” is often used as a shorthand for compositions tinkling in the background – it is, in fact, the name of a corporation that dates to 1934 and which originally specialised in background music for stores and other environments.

Muzak was soon spreading its tendrils far and wide. In the Fifties, the company – then part of Warner Music – designed playlists that were pumped into offices to enhance productivity. The music would become faster and “brasier” – encouraging employees to work faster.

Such “innovations” led to accusations of brainwashing. Still, many influential figures were attracted to the idea of using music to enhance people’s moods. In the mid-1960s, President Eisenhower had Muzak pumped into the West Wing of the White House, while NASA played Muzak to soothe astronauts during times of inactivity.

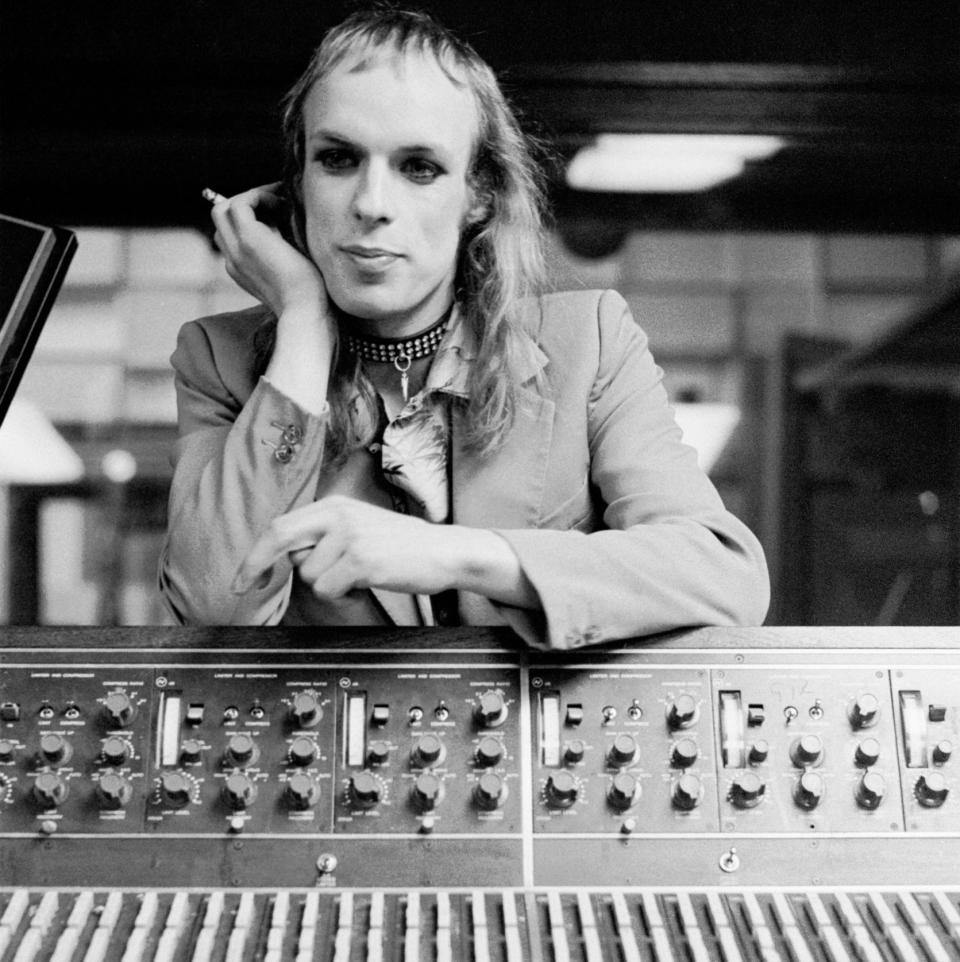

The Muzak brand still exists today, though it went into decline in the Seventies when supermarkets opted to play pop music instead. At the same time, ambient music was becoming more artistically credible. There was a huge leap forward in 1978 when Brian Eno released Music for Airports, a collection of tape loops which he conceived of as sound instillation that would defuse the anxiety people feel in the departure lounge. He wanted, he explained, to “induce calm and a space to think”.

Music for Airports was a landmark for background music. Eno wasn’t the first serious artist to experiment with ambient compositions. But he was a rock star: a former member of Roxy Music and collaborator with David Bowie. When he released an LP of barely audible parps and whirrs, people sat up and listened.

All these decades later, background music continues to get under our skin. Warner Music has agreed a 20-album distribution deal with German mood music app Endel, which uses algorithms to create “personalised soundscapes to give your mind and body what it needs to achieve total immersion in any task.” Five records have already been released: Clear Night, Rainy Night, Cloudy Afternoon, Cloudy Night and Foggy Morning. These sound like blends of herbal tea – but could be the future of music.

With all that going on, André 3000’s pivot to ambient flute compositions feels less like a shot in the dark than blue-sky thinking. New Blue Sun has earned some of the best reviews of his career. “Beautiful, demanding, and among the most fascinating artistic left turns in recent memory,” swooned Pitchfork. The New Yorker heralded André for building “toward a sublime, overwhelming crescendo—a feeling of awe”.

He’s also made the record books. I Swear, I Really Wanted to Make a “Rap” Album but This Is Literally the Way the Wind Blew Me This Time, the LP’s 12 minutes 20 seconds opening track, has entered the Billboard Hot 100 – the longest-ever song to chart in Billboard history.

He has responded to the hubbub around the project with a shrug. “You need to keep doing things that keep you inspired. I’m just trying to find a way to keep going,” he said recently. “Sometimes, if you hit a wall at one thing, changing it up lets you reach that next step – like Picasso switching between sculpting and painting. I’m always trying to do what allows me to find wonder.”

Part of his wondering and wandering has seemingly led him to the doors of a sub-section of chill-out music known as “Dungeon Synth”. Fair enough, “chill” is not quite the word that springs to mind when artists have names such as “Lunar Womb”, “Old Sorcery”, and “Depressive Silence”.

Nonetheless, these musicians have carved out a distinct corner of mood music with melancholic, epic soundscapes inspired by JRR Tolkien and Dungeons and Dragons. And by the suspicion, it’s been all downhill since King Arthur called time on the Round Table.

André 3000 has never publicly talked about Dungeon Synth. The influences on New Blue Sun are, in the first instance, Afro-futurism and free jazz. However, many in the “DS community” have twigged a connection. Particularly in the final track on his LP, Dreams Once Buried Beneath the Dungeon Floor Slowly Sprout into Undying Gardens – as “typical” a Dungeon Synth title as you could imagine.

“André 3000 just dropped the Dungeon Synth album of the year; it’s over for this genre; pack it up, folks,” tweeted one fan. “A lot of André 3000 fans are going to end up getting into dungeon synth thanks to his new record,” said another.

Dungeon Synth mostly exists on the music website Bandcamp. Once you go down the rabbit hole, it is a fascinating labyrinth. Dungeon Synth is about yearning for misty mountains and far-away dells – a vibe conjured by creaking synthesisers and swirling ghostly beats. It will also lead you to adjacent genres such as “Dino Synth” – defined as “Prehistoric-themed Dungeon Synth about the Stone Age, cavemen, dinosaurs of the Mesozoic era, and pre-Cambrian times”.

“Dungeon Synth is the sound of the ancient crypt. The breath of the tomb, that can only be properly conveyed in music that is primitive, necro, lo-fi, forgotten, obscure, and ignored by all of mainstream society,” explained the influential Dungeon Synth Blog in 2011 in what has come to be regarded as the standard definition of the milieu. “When you listen to dungeon synth you are making a conscious choice to spend your time in a graveyard, to stare, by candle-light, into an obscure tome that holds subtle secrets about places that all sane men avoid.”

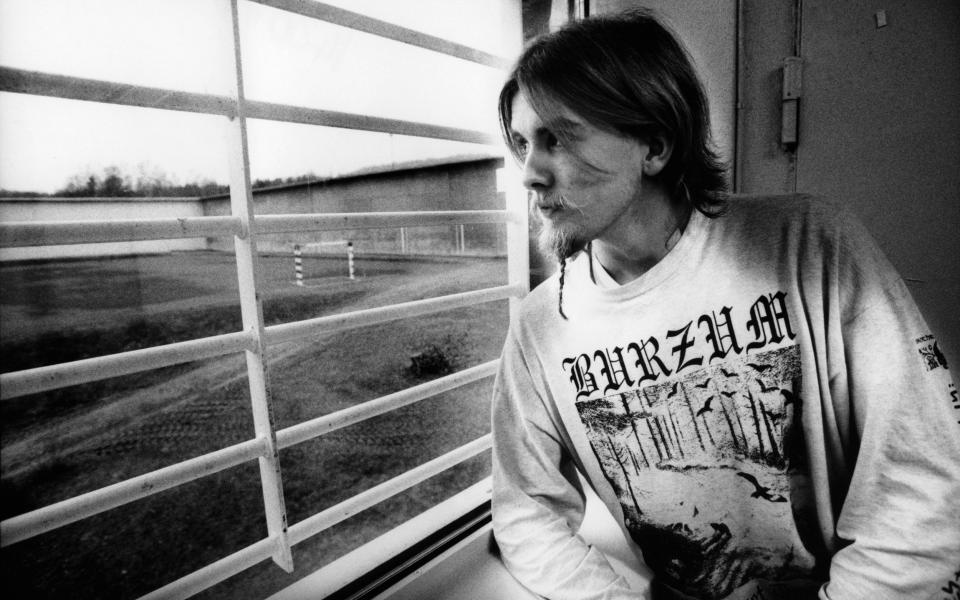

It sounds creepy – but is actually cosy and comforting. That’s despite its arguably violent origins. One of the first Dungeon Synth records is credited to notorious Norwegian death metaller Varg Vikernes – aka Burzum – who was jailed in 1994 for the murder of a rival musician. Behind bars, he didn’t have a guitar. He was, however, allowed a synthesiser, which is how he wrote one of the earliest acknowledged Dungeon Synth documents, Dauði Baldrs.

But the chill-out boom is not universally welcomed. Some musicians have complained it is soulless and AI-driven – “elevator music” for the 21st century.

“Ambient music is the great wellspring – but also the bane of my existence,” electronica composer Tim Hecker said to the New York Times, in the context of his music becoming popular on Spotify playlists. “It’s this superficial form of panacea weaponised by digital platforms, shortcuts for the stress of our world. They serve a simple function: to ‘chill out.’ How does it differ from Muzak 2.0, from elevator music?”

The “elevator music” insult has been levelled at André 3000 and his new record. He doesn’t seem too fussed. Whether drawing on jazz, Afro-futurism or Dungeon Synth, his recent sonic excursions have apparently brought peace of mind. While he had enormous success as one-half of Outkast, the experience ultimately burned him out, and he sought new musical challenges. He has found what he was seeking with his forays into flute-playing. For fans willing to go there – those who can handle the flute – it’s a journey worth joining him on.