The Implications of Prison Flipping

Photo courtesy of the Lucy Burns Museum and Workhouse Arts Center

Today, a resident on the ground floor of Liberty Crest Apartments in Lorton, Virginia, might be taking a call in their private backyard, a fenced off, grassy area connected to others in the complex. This person might pass through the buildings’ brick archways before going to work, or even turn onto Reformatory Way to see a neighbor on a Sunday afternoon. And while their day-to-day life may read as standard, the markers of their routines—the yards, the bricks that make up their building’s exterior, the street names—hold a much darker history.

Twenty-three years ago, Liberty Crest Apartments was one of eight prisons that made up Lorton Correctional Complex. The other seven have either been torn down or are some combination of an art gallery, a museum, and a supermarket. Conceptualized by Washington, D.C., architect Snowden Ashford, part of Lorton’s initial layout reflected the then “progressive” ideology of reform, which meant specific design choices like open dormitories rather than cell blocks. Some of those dormitories now house D.C. commuters, their greenery previously occupied by incarcerated men playing basketball or handball on what was the prison rec yard, the bricks of their archways handmade by some of the first men confined to this complex in the early 1900s.

“It’s definitely weird for us who actually served time here to see people paint and live in it,” says Karim Mowatt, a filmmaker and writer who was one of the last people to leave Lorton before it closed in 2001. “But if you look at America’s history, everywhere is littered with blood to a certain extent.”

![“While we were in [Lorton], they had started developing around the prison. We knew it was a matter of time before the prison was going to shut down because the land was in a prime location,” shares Karim Mowatt. Seen here, an aerial view of the now Workhouse Art Center, which includes the Lucy Burns Museum.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/TqFqwlK6hAH5d2t.MbY3KQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcyMA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/architectural_digest_422/a8a19b1786ff4d6ab0e506a09540426b)

You can find traces of carceral facilities in repurposed sites all over the United States, from a regenerative farm in North Carolina to hotels and Airbnbs in Texas, Massachusetts, and New York. And while some of these prison flipping projects acknowledge their past as a contributor to the mass incarceration that defines America, others use puns and photo opps with mugshots to make light—and money—off of the criminal legal system. For $195 a night, an Airbnb listing in Ephraim, Utah, boasts an offer to “Spend the night in JAIL!” with “stunning limestone…cells,” while another in Hampton, Iowa, assuages prospective guests that “the doors will not be locked behind you.” Similarly, The Inn at Warm Springs, Liberty Hotel, and The Cell Block have opened what were formerly cell doors with sensationalized headlines to entice guests. While these hotel websites give a brief overview of their past, their insensitive/offensive puns (“break the chains of monotony”) and casual nods to confinement (“graffiti left by some long forgotten convict”) signify a gross lack of understanding when it comes to the gravity of mass incarceration.

It’s hard to find a system—which confines 1.9 million people across 1,566 state prisons, 98 federal prisons, 3,116 local jails, 1,323 juvenile correctional facilities, 142 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian country jails—funny. And yet, in the same way many Americans dismiss the history of enslavement, we have managed to belittle a criminal legal system and therefore dehumanize the countless communities impacted by it through these versions of prison flipping. Like the majority-white college parties or alumni reunions and corporate events held on plantations, “these [institutions] are trying to colonize the optics of suffering to make it trivial,” says artist Jared Owens, whose work often responds to his experience with incarceration. “It’s just as bad as Black face.”

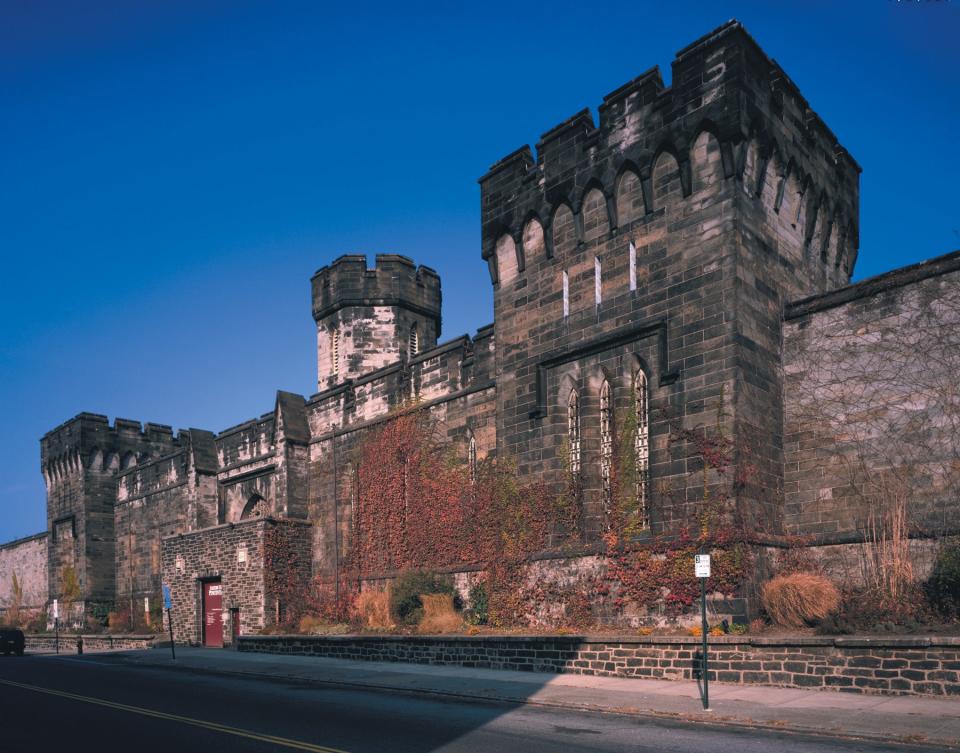

Unsurprisingly, some couples are happily choosing former prisons as their wedding venues, with tone deaf themes like “til death do us part.” One known venue in this category is Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP), a museum in Philadelphia that formerly served as a prison from 1829 to 1971. “It was America’s first penitentiary,” shares Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter, an artist, scholar, and Philly native who both worked at the museum and experienced the criminal legal system in Pennsylvania. “All other penitentiaries around the country were modeled after their radial design, which allowed a small number of people to monitor or surveil a larger group.” Now, that design serves a variety of other purposes.

Sean Kelley, who oversaw the visitor experience at Eastern State Penitentiary for nearly 30 years, says that weddings previously comprised a small portion of the annual budget. The larger line item has, for years, been the museum’s annual Haunted House. Formerly called “Terror Behind the Walls,” the show only removed all references to prisons, including people dressed up as incarcerated zombies, just before the pandemic. At the time, the museum was financially dependent on the Halloween event and, at first, “it just seemed like a transactional situation” to Kelley. His perspective drastically shifted when he began regularly visiting prisons and becoming close with people directly impacted by incarceration. “I had no idea how much that proximity would change what I was doing,” he admits.

The museum began to replace costumed tropes with new staff members who had come home from prison themselves, like Russell Craig, the Brooklyn–based artist who, as part of the museum’s inaugural cohort of formerly incarcerated hires, would give tours and discuss his work juxtaposed with displayed murals painted by someone incarcerated at ESP in the 1950s. They also brought on Owens for an installation in 2017 that, by way of a symbolic burial, allowed the artist to “put my past to rest.” Kerry Sautner has spent her first year as CEO of Eastern State Penitentiary interrogating how the museum can shed a harmful past and, instead, “take a place of trauma and do healing work with it,” much like what Owens describes. Codifying workforce development for formerly incarcerated people is one way she hopes ESP can eventually “walk the walk.”

Like Eastern State Penitentiary, there are many institutions that are confronting their history and seeking to respond responsibly, like the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) in Raleigh. Sitting on the land of a demolished youth detention center, NCMA has preserved the detention’s smokehouse as a tangible reminder of its history. “We’re trying to talk more about the prison industrial complex and how our history intersects with that,” says the museum’s assistant curator of contemporary art, Maya Brooks, who is intent on acquiring more thematically aligned work, like that of native Sherill Roland, to inspire engagement.

Some of these institutions, however, have experienced controversy when interrogating their own history. Formerly a two-room county jailhouse, the Davenport Jail in Northern California now sits under the purview of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art. In 2022, the museum collaborated on an exhibition with the public scholarship initiative Visualizing Abolition and Writing on the Wall, a traveling project by Baz Dreisinger and Hank Willis Thomas that features essays, poems, and other notes by people who have experienced incarceration globally. Before the exhibit, Robb Woulfe, the museum’s executive director, shares that “a number of narratives around [the jail] were inaccurate.” Locals had previously positioned it as “a Disney version of a roadside jail where a couple of ne'er do wells drank too much,” i.e. an Andy Griffith esque jail unlike other violent carceral facilities. But the research behind this partnership found that Davenport Jail had what Dreisinger describes as “an evil carceral history,” including the containment of many Chinese migrant laborers. Revealing the true history behind the space upset locals, even resulting in defaced signage.

With discomfort also came supporters who would sit on the floors of the old cells, reading narratives by incarcerated people collected by Dreisinger during her years teaching inside prisons. “It opened our eyes to how we can use these historic spaces,” Woulfe says while reflecting on both the indoor exhibit and Flowers for Incarcerated Mothers, a garden project led by jackie sumell that simultaneously sat outside of the jail-meets-museum.

The Writing on the Wall

By bringing in people with lived experience as central narrators, collaborators, and leaders, these institutions have an opportunity to repair centuries of harm created within these spaces. At Bybee Lakes Hope Center in Portland, Oregon, this type of restoration looks like transforming the previously abandoned Wapato Correctional Facility into a campus servicing people who have experienced homelessness. The 17-acre property is home to a half-acre garden, an orchard, art studios, and a full daycare center. Built as a transitional dormitory for $58 million, the building sat unused for 18 years.

In 2018, philanthropist Jordan Schnitzer purchased the facility hoping to revamp the site by partnering with a nonprofit to help solve Portland’s homelessness crisis. “I worked with 18 nonprofits, and for whatever reason, the county had a negative attitude of repurposing this and said it couldn't be done,” Schnitzer shares. So, when Schnitzer met Evans, a leader who lived on the streets for over two decades, a beautiful partnership was born. Now covered in trauma-informed colors—brighter pigments that Evans says “have a softer feel”—and storefront windows to let lots of light in, Bybee Lakes touts 318 beds for people seeking services.

![“So many people talking about [homelessness] have masters and PhDs in gerontology or other degrees—but they weren't people on the street,” says Jordan Schnitzer of the value in having leadership and staff that intimately understand what participants are going through. 75% of employees who work directly with participants at Bybee Lakes Hope Center have lived experience.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/QYv.JyHYjVJ1US73WVRc.A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTgwNQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/architectural_digest_422/5991b574244a2a03a9d8872a129c8db5)

Yellow Minimalist Reminder Facebook Post - 8

Efforts to create second lives for carceral facilities must prioritize acknowledging their history and the stories of those they confined (and, in some cases, are still confining, since many jails or prisons are shut down only to crop up in another form nearby). There’s a placard in Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, the latest site by the Equal Justice Initiative, that reads, “The tiny fingerprints of enslaved children who turned bricks as they dried can be seen today on the bricks of historic Charleston buildings.” On a Monday evening in April, I was reminded of this tangible echo of enslavement while speaking with Mowatt, the aforementioned filmmaker who served time at Lorton before part of the building was turned into apartments. “You can still see scratches on the floors from people sharpening their knives,” he pointed out. Perhaps preserving these traces is one step in breaking this country’s relationship to erasure.

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest