An impossible dream? The trouble with utopian dramas

When the UK entered its first lockdown in March, there was a lot of talk about using this enforced pause as a chance to reassess and maybe even remake the world. As the months took their toll, that energy waned. But with a vaccine rollout and a man for whom empathy is not an alien concept about to take up residence in the White House, it does not seem unreasonable to start imagining a better tomorrow.

In literature there have been many attempts to create utopias, other lands more golden than our own, untainted, Edenic, more equitable societies in which war and poverty are things of the past. From Thomas More’s 1516 book, which gave us the term, through the writings of William Morris and HG Wells, to the comic-book monarchies of Wakanda and Themyscria (respective homelands of Black Panther and Wonder Woman), to one of the most enduring utopian societies of them all – the Star Trek universe, people have used art to imagine better worlds.

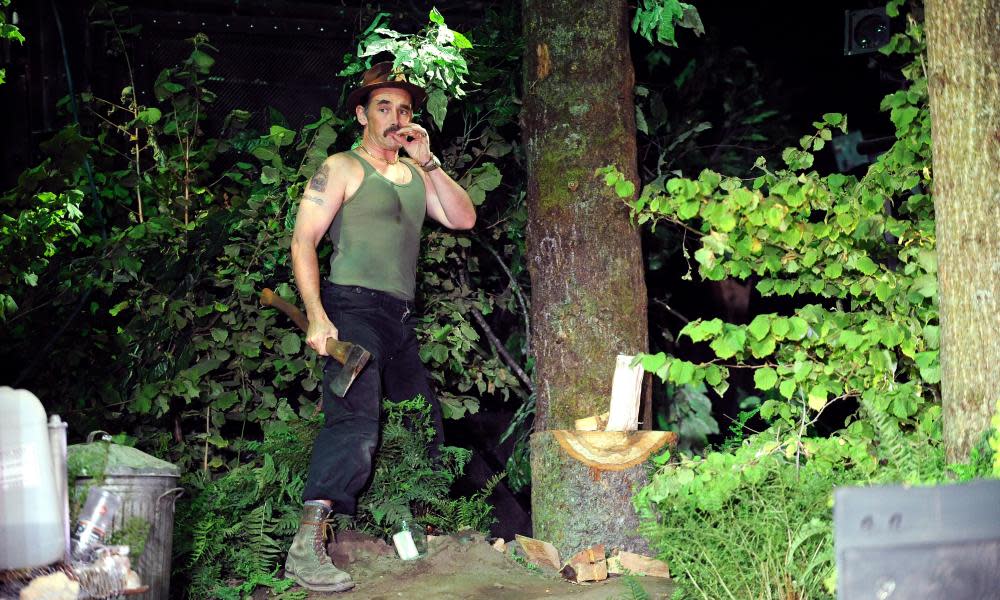

When trying to identify a play that exemplifies these ideas, it gets a little trickier. There are numerous dystopian plays: Caryl Churchill’s prescient Far Away, Dawn King’s Foxfinder, Jennifer Haley’s The Nether, Karel Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots, Alan Ayckbourn’s interminable The Divide, but it’s harder to name a truly utopian play. Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem could be read as utopian if viewed through the eyes of its protagonist, Rooster Byron. Ella Hickson’s The Writer explores the concept of feminist utopia, but as one of a series of narrative resets and rug-pulls. But the list is not a long one. Is there something that makes them particularly challenging to write?

To playwright Vinay Patel, whose television credits include Doctor Who, “actual utopias – as opposed to the places that just seem to be utopias – are, by themselves, inherently undramatic. But it’s the contrast they provide to dystopias or, indeed, our present day that make them compelling.”

For Anna Jordan, a Bruntwood prize-winner for her play Yen, and part of the writers’ room for Succession, “perfect societies are harder to imagine because we have access to social media and more information than anyone has had before. It makes it harder to believe that while there is so much difference in the world there could be such a thing as a perfect society.”

From More onwards, all utopias are essentially refractions of the world in which they were created. Utopian fiction necessarily reflects the preoccupations, struggles and divisions of the time and culture in which it is produced. The various Star Trek offshoots still bear the hallmarks of the explicitly post-conflict universe created by Gene Roddenberry in the 1960s.

Utopias demand contrast. “This other world has to exist in relation to a world that we currently inhabit,” says Joel Horwood, whose 2014 play This Changes Everything contains utopian elements. The play takes its title from the book by Naomi Klein and was written as part of Platform, an initiative from Tonic Theatre aimed at addressing gender imbalance and inequality in theatre by creating plays for large casts of women. It depicts a group of young women, disillusioned with the excesses of capitalism and society’s failure to act on the climate crisis, who form an isolated community of their own. As in Horwood’s play, many utopias are isolated from the wider world, pockets of perfection.

This Changes Everything was written in what was, says Horwood, “a much more positive time than now”. He was inspired to write it by thinking of the world in which young women were growing up and “how it was hostile and what active choices could they make to reduce that ubiquitous hostility”. Their decision, to leave the world and start over, contains a utopian impulse: “They make a choice to go somewhere and start afresh. There’s an active choice to make a new possible society.” But, despite their hopes, cracks have already appeared by the time newcomers show up. Ultimately, the play shows “how pervasive capitalist ideology is and how, whatever you try and do to keep it out, it can seep through”.

In much utopian writing, there’s an understanding that any ideal society would inevitably be complicated by the people living in it; that the boundary between utopia and dystopia is often porous and always intensely subjective: that one person’s idea of paradise is another’s idea of hell.

The word that crops up most often when discussing utopian fiction is conflict, or the lack of. Playwright Tim Foley, whose play about robot nuns, Electric Rosary, was due to be staged at Manchester’s Royal Exchange this summer, says “there is a generation of playwrights who have been drilled into believing that drama is conflict; that characters have hidden wants, unfulfilled needs. Is this compatible with a utopia? I don’t think so. If utopia is the destination, a play fetishises the nooks and crannies of the journey. We are conditioned to think that anything other than this is dull.

“We’re always waiting for things to turn nasty because those are the story shapes we’ve had drilled into us,” says Patel. “I find it hard to conceive of the destination as more beautiful or humane than the journey there. For me, utopia resides in interactions between people, acting with care and compassion, understanding and kindness. Behaviours create and sustain utopias, not grand designs.”

To Jordan, whose play about soldiers coming home from war, The Unreturning, was partly set in a dystopian future, says “utopia feels perfect and theatre stories to me feel inherently imperfect, messy, flawed”.

Might some theatrical forms be better suited to utopianism than others? Could the feelgood musical be considered utopian? The Canadian musical Come from Away, about a community rallying to help planeloads of stranded people in the aftermath of 9/11, certainly leans in that direction. It paints a picture of humanity at its best, with what conflict there is located in figuring out how best to help people. Could the same be said about the frothy, escapist musicals of the 1930s? Musicals, says Patel, “are often full of joy and characters that bend towards misunderstood rather than outright evil. Is Mamma Mia! a utopian play? I could believe it.”

It could be argued that there is something inherently utopian about theatre itself, about the act of coming together and thinking and hoping together. Performed at BAC in London before lockdown, When it Breaks it Burns, a piece of theatre made by a group of young Brazilian activists about their experiences of the São Paulo school occupation movement, is a perfect example of this. It felt utopian both in the way it was made – the young people owning their story and sharing it – and the way it showed its audience how to make change.

Horwood says he wrote his play, in part, “to try and generate a practical act of hope”. He wanted This Changes Everything to encourage discussion in rehearsal rooms about what the world could be. “It felt like the utopianism was in the process,” he says.

“Theatre is waking up to the realisation that there are many stories and voices that have been marginalised for years and that deserve to be heard,” says Jordan. With any utopian story the question has to be asked: whose vision are we witnessing? What system is it a product of? “Utopianism is as much about the way you tell a story as the story you tell.”