Jane Goodall Isn’t Letting Coronavirus Stop Her From ‘Doing What I Do’

If you were to write Dame Jane Goodall, the famed primatologist, and ask how to follow in her footsteps, she’d likely give you advice her mother gave her when she was young: “If you really want to do this, you're going to have to work really hard. Take advantage of every opportunity,’” she recalls. “If you don't give up, you'll probably find a way.”

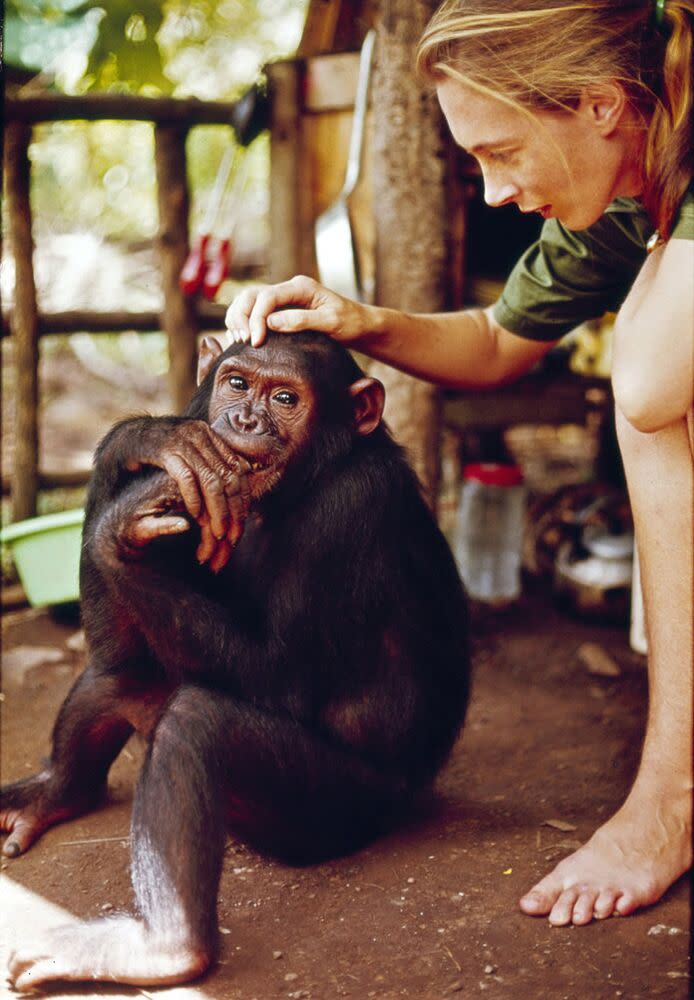

To say she found a way herself is an understatement: Goodall began her career in 1960 with a fateful trip to study chimpanzees in their natural habitat at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, where she slowly earned the trust of a pack of the primates she studied. As one of the first women to enter the field, she broke boundaries for women scientists and for the study of animals altogether; she was one of the first to realize chimps and other primates exhibit emotions and displays of affection much the same way humans do. It took a lot of work to make her breakthrough discoveries, however — and even more work to get to Africa at all.

When InStyle caught up with Goodall for our Badass Women series, she was at home in Bournemouth, England — “in the house I grew up in,” she adds — which is a rarity for her. “Since October ‘86 until the [coronavirus] shutdown, I’ve been 300 days a year around the world,” she explains. She returns to Bournemouth in between trips, and it’s there that she keeps the Dr. Doolittle books that she read when she was 8; it was those books and a second-hand copy of Tarzan of the Apes she found at age 10 that sparked her dream to work with animals.

But that dream didn’t have a blueprint: At the time, the field was comprised almost exclusively of men, and Goodall’s parents couldn’t afford to send her to college anyway. (In the early 1950s, fewer than 6% of American women completed at least four years of college, so she definitely wasn’t alone.) She took a secretarial course instead, which paid off in a matter of happenstance when the then-23-year-old met archeologist Louis Leakey in Kenya, after joining a friend on a trip to their farm: “Amazingly, that boring secretarial course…!” she said. “Two days before I met Louis, he'd lost his secretary. She suddenly quit, and there I was.”

It was a back door into a dream job, at a time when women were most frequently expected to be stay-at-home mothers. Not one to settle, Goodall used that secretary role as an opportunity to learn as much as she could, and Leakey eventually sent her to study the native chimpanzee population in Tanzania, even though there were virtually no women in the field of primatology. Undaunted, Goodall spent “three or four months” trying to earn the trust of a group of chimpanzees who kept running away from her. “It was really depressing,” she says. But when one chimp Goodall had named David Greybeard finally chose to stay when she approached him, she also earned the trust of the rest of the pack.

That trust allowed her to debunk previously held beliefs about the mammals. Her discoveries, she recalled, “opened the door so students today can study animal personalities, emotions, and especially intelligence.” She did her part to ensure that young people could learn as much as she did about chimps, as well as advocate for their environment, by founding Roots & Shoots in 1991; the organization, she says, “is about young people getting together, discussing problems. It began with 12 high school students in Tanzania and it's now in 65 countries.”

The organization’s work couldn’t have come at a better time, either: Most people had just begun understanding the catastrophic effects of climate change on the environment, and how deforestation and animal testing were impacting the animals Goodall and others cared so much about. “I was traveling around the world, talking about how chimpanzees' numbers were decreasing, and the forests were being cut down and they were being used in medical research, treated really cruelly,” she says. “And I knew I had to try and do something. I didn't make a decision; the decision happened.”

RELATED: Panicked About the End of the World? You Might Have "Eco-Anxiety"

But while it was a fight she wouldn’t be able to take on alone, she was lucky in that she didn’t have to. “As I was traveling, I was meeting young people who seemed to have lost hope” about the advancing state of the climate crisis, she says. “And I thought, yes, we have compromised your future, we've been stealing your future. But it's not too late for you to do something.”

And young people, some emboldened by Goodall's living legacy, have done more than show up: Activists like Greta Thunberg, Xiye Bastida, and Jamie Margolin, have used the collective power of their organizations to hold lawmakers accountable and advocate for change that benefits everyone. They’re adapting to social distancing in the era of COVID-19, too, by staging digital strikes and organizing on Zoom and other platforms.

RELATED: Greta's Not the Only One — 7 Other Young Climate Activists to Know By Name

While the efforts to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus have put a hold on the now-86-year-old Goodall’s travel, she’s not letting such restrictions slow down her work, either. “I'm working from home and doing my best to carry on doing what I do,” she says. “I do feel I'm on a mission, [and that] I'm in this world with this purpose.”