How This Landscape Design Studio Uses Drones and Tech to Create Green Spaces

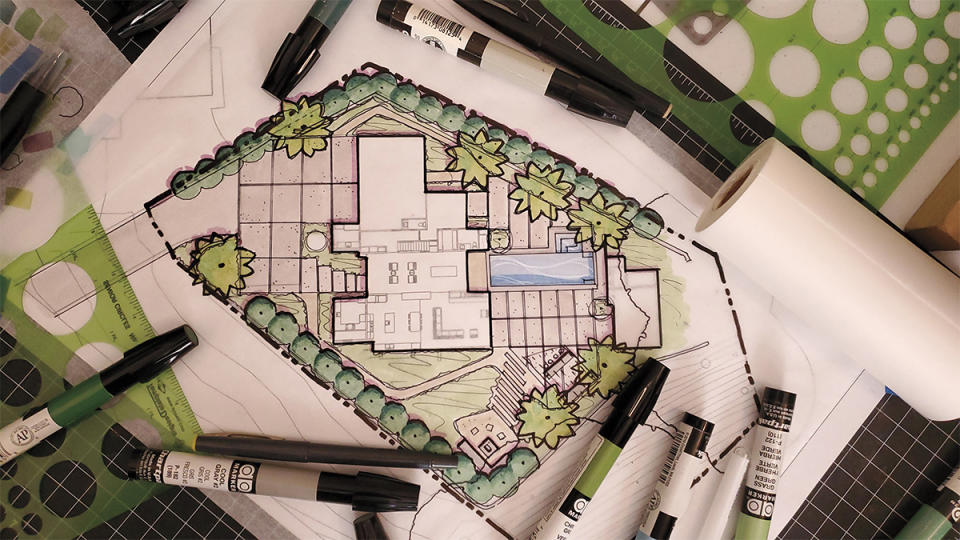

At the start of a recent backyard overhaul for a family of five in Montecito, landscape designers Eric Arneson and Nahal Sohbati watched a small gray drone make its ascent into the blue sky. They then guided the machine around the property, using it to take photos and video of the one-acre lot, collecting data that would help them design the project’s many features: a new pool, a natural play area, stone retaining walls, and native plantings. To fill out the infrastructure already in place, Arneson and Sohbati planned to utilize palms of varying heights and colors along with indigenous species such as Catalina currant, hummingbird sage, and California coffeeberry.

It was a complex job that required the help of contractors, fabricators, and plant suppliers; having a drone-generated 3-D representation of the terrain optimized everyone’s tasks. “It’s a digital twin of the site that we keep in our computers,” Sohbati explains. “And it helps collaborators to communicate better.”

More from Robb Report

How an N.Y.C. Native Created a Resort-Like Retreat in New Jersey

Agnes Studio Talks Latin American Design With Art Historian Ana Elena Mallet

A Classic Basketball Shooting Game Just Got a Luxe Makeover for Your Home

This kind of thinking, including the eagerness to experiment with new technologies, is what first drew Arneson and Sohbati together. The two met at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, connecting on a personal and an intellectual level over a passion for landscape architecture and a shared vision of the future of the industry. In 2018, shortly after graduation, they married, moved to Santa Barbara, and founded Topophyla, a landscape-design studio focused on process innovation and sustainability. “We wanted to experience this field in our own way,” says Tehran-born Sohbati, who studied interior design in Dubai before moving to the West Coast, “and experiment with new technologies and new materials.”

The general perception of work relating to gardens and yards skews quaint. A vision of shovels, rakes, and lots of pruning squares with the romantic view of toiling with one’s hands. But like many industries, landscape design is evolving, and Topophyla is carrying a torch into the future.

Arneson and Sohbati had foreseen the potential of drone imagery while working with the technology at the Academy of Art. They homed in on the tool as soon as they launched their studio, using sophisticated machines to create 3-D renderings of the landscapes they were designing. These renditions look similar to images found on Google Earth but appear in higher definition and come packed with ultra-specific data such as the height of existing trees, the various slopes of a field, or the ratio of vegetation to built-up areas—all information that can help the team formulate the least disruptive plan for excavation and planting. After a project’s completion, drone surveys can assist with evaluation and maintenance, creating a way for Topophyla to check, from a holistic vantage point, that its designs are flourishing, plus providing an invaluable resource when it comes to updating or expanding a project.

“It’s a fantastic tool for a landscape architect to understand land from a new perspective, as opposed to just satellite images or maps,” says Arneson, a native Californian with a background in fine art and botany. “We use it for every project.”

As a technology-focused studio, Topophyla is naturally inclined to play around with A.I., and the firm is gaining recognition for it. In 2022, Sohbati and Arneson were tapped by Open A.I. to test the beta version of DALL-E, which generates photorealistic imagery based on descriptive text prompts, and provide feedback to make it more useful to landscape designers. “Right now it’s a creative toddler,” Arneson says. “It thinks of things an adult wouldn’t think about, like creating a slide going through a tree in a playground. As far as being practical, it’s just not there yet—but it will be.”

The knowledge that A.I. will inevitably permeate landscape design is both exciting and unsettling to the couple. Arneson and Sohbati are acutely aware of potential downsides, including a shrunken job market and the risk of unscrupulous professionals creating fake portfolios with images that look just like the real thing. As for the upsides, it could be a time-saving tool that generates multiple ideas quickly while also taking care of routine tasks such as code enforcement.

Yet, as much as Topophyla’s founders embrace new technologies, their true passion is more elemental: creating green spaces that are both authentic and sustainable. To them, sourcing locally is just as important in the world of landscaping as it is in the world of food; their garden designs are brimming with indigenous Californian plants and, if possible, specimens native to a site’s immediate surroundings. Some favorites are California lilacs and pipevines, coyote bushes, sage, and seaside daisies—all of which, not insignificantly, cater to endangered types of butterflies, bees, and other insects. The firm looks to replace traditional lawns with low-maintenance and environmentally friendly fescue grasses, which require less water and less mowing.

“The more people are exposed to the beauty of native plants and the intricate interconnectedness of birds, pollinators, and other life cycles, the more they will realize the aesthetic and ecological value they’re missing out on,” says Sohbati, adding that she considers conventional flat lawns to be devoid of character.

Arneson also views such hyperlocal sourcing on an ethical level, framing the use of native plants as a form of patriotism. “It’s celebrating what’s here,” he says. “Traditional landscaping is a vestigial remnant from Europe and doesn’t apply to most of America. It’s time for things to change.”

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.