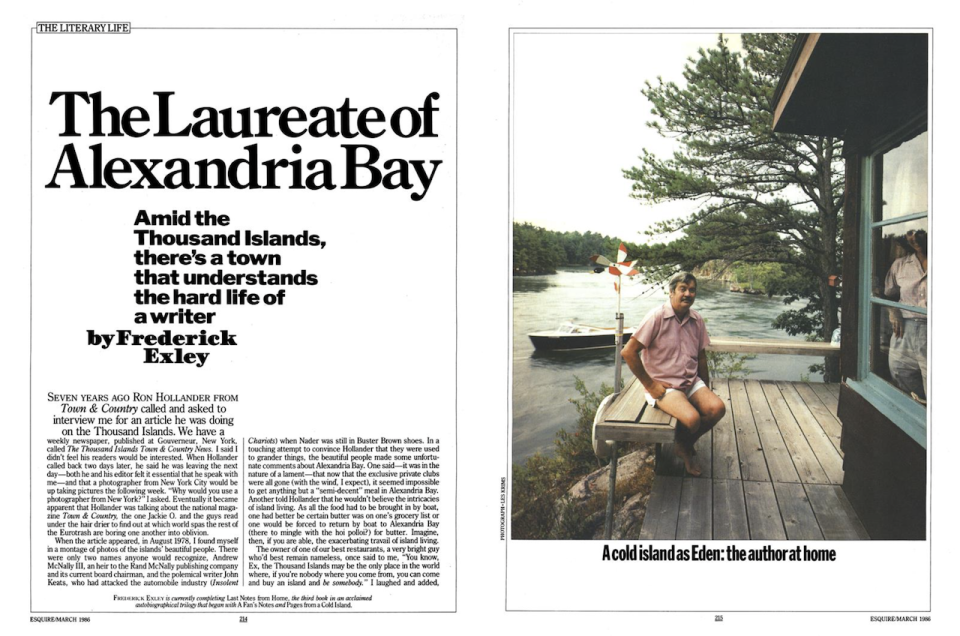

The Laureate of Alexandria Bay

This article originally appeared in the March 1986, issue of Esquire. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

Seven years ago Ron Hollander from Town & Country called and asked to interview me for an article he was doing on the Thousand Islands. We have a weekly newspaper, published at Gouverneur, New York, called The Thousand Islands Town & Country News. I said I didn’t feel his readers would be interested. When Hollander called back two days later, he said he was leaving the next day—both he and his editor felt it essential that he speak with me—and that a photographer from New York City would be up taking pictures the following week. “Why would you use a photographer from New York?” I asked. Eventually it became apparent that Hollander was talking about the national magazine Town & Country, the one Jackie O. and the guys read under the hair drier to find out at which world spas the rest of the Eurotrash are boring one another into oblivion.

When the article appeared, in August 1978, I found myself in a montage of photos of the islands’ beautiful people. There were only two names anyone would recognize, Andrew McNally III, an heir to the Rand McNally publishing company and its current board chairman, and the polemical writer John Keats, who had attacked the automobile industry (Insolent Chariots) when Nader was still in Buster Brown shoes. In a touching attempt to convince Hollander that they were used to grander things, the beautiful people made some unfortunate comments about Alexandria Bay. One said—it was in the nature of a lament—that now that the exclusive private clubs were all gone (with the wind, I expect), it seemed impossible to get anything but a “semi-decent” meal in Alexandria Bay. Another told Hollander that he wouldn’t believe the intricacies of island living. As all the food had to be brought in by boat, one had better be certain butter was on one’s grocery list or one would be forced to return by boat to Alexandria Bay (there to mingle with the hoi polloi?) for butter. Imagine, then, if you are able, the exacerbating travail of island living.

The owner of one of our best restaurants, a very bright guy who’d best remain nameless, once said to me, “You know, Ex, the Thousand Islands may be the only place in the world where, if you’re nobody where you come from, you can come and buy an island and be somebody.” I laughed and added, “Yeah, and I bet when that Datsun dealer in Harrisburg is having his Friday afternoon cocktail with the guys and says, ‘Well, I got to get goin’ to my island up at Alexandria Bay,’ those guys are thinking, ‘Don’t let the door hit you in the ass on the way out, ’ or, ‘T.T.M.F.,’” a local farewell I’ll leave to the reader to fathom. So much for the regal-necked delusions of our island people.

The Big Guys were on our islands once, make no mistake about that. In 1872 George M. Pullman, who had revolutionized the train-car industry with his sleepers and dining cars, invited President Ulysses S. Grant and his military aide, General Phillip A. Sheridan (Phillip H. was the Civil War Union general), to his Alexandria Bay island for five days of fishing. Grant knew the area well. While a young lieutenant he had been stationed for four years at Madison Barracks, forty miles west of here, at Sackets Harbor on Lake Ontario, the site of a famous naval battle during the War of 1812.

In a photo taken in front of Pullman’s Camp Charming, Grant is sitting with General Sheridan on an Indian blanket on the grass beneath shade trees. Grant is fifty, ruggedly handsome; his close-cropped hair and beard are vigorous and without gray; he is big-shouldered, barrel-chested, ham-handed, and heavy-legged, an imposing figure. For all that, there is a kind of Lincolnesque sadness and pensiveness about him, as though seven years after the Civil War he still hasn’t put aside the traumatic horror of it. He appears both more thoughtful and more intelligent than a man who finished in the bottom half of his class at West Point should appear.

Ordered to rest by his physicians, President Chester A. Arthur came a decade later, in 1882, checked into the Bay’s Crossmon House, hired a guide, fished for ten days, and had his shore dinners of freshly caught northern pike and bass. Although the press corps that followed these Presidents was nothing like the one that follows a President today, still the media were here, word of our lush green islands went out, and things would never be the same for either the Iroquois or the locals.

The railroad, coal, tobacco, and Wall Street millionaires came and, from our native oak, sandstone, limestone, and granite, built their mansions. The luxury hotels expanded, and the tourists followed to relax, fish, and ride the tour boats. All this culminated, then started to decline, with the arrival, in 1893, of George C. Boldt, still the biggest enigma that ever graced our islands. Boldt was either a Teutonic wacko or a genius, or both, a combination that has never proved incompatible.

Born in 1851 on the island of Rugen, in the Baltic Sea off Prussia, Boldt at thirteen emigrated to America and began his American experience as an omnibus (busboy) and kitchen helper. By the time he was forty-two, when he first came to Alexandria Bay, he was the manager of the Waldorf (he would later lease the hotel from the Astors) and the owner of Philadelphia’s Bellevue-Stratford. He would eventually earn as much as $500,000 a year from the Waldorf.

Boldt had become known as the world’s greatest innkeeper and the Prince of Bonifaces, and his genius lay in public relations (he was among the first to introduce room service, freshly cut flowers in every room, and so forth) and personnel selection. The first man he hired for the Waldorf, for example, was the maître d’ at Delmonico’s, Oscar Tschirky, who later became the legendary Oscar of the Waldorf. It was while cruising on the St. Lawrence as Boldt’s guest that Tschirky created Thousand Island dressing, which Boldt promptly introduced at his two hotels.

Detecting that Hart Island, an average swim from the town docks, was somewhat heart-shaped, Boldt bought it from the estate of Congressman E. Kirke Hart, renamed it Heart Island, and remodeled Hart’s place into a granite and wooden “cottage” that would make anything in today’s Beverly Hills appear a piece of trifling and contemptible tomfoolery. Unsatisfied, Boldt then razed that structure and began what for him, and for us, proved a nightmare. With granite from his own quarry on Oak Island, ten miles downriver, he built a six-story castle in which he envisioned 127 rooms, forty bedrooms, thirty full-size bathrooms, a basement swimming pool, a library finished in Flemish oak, fireplaces of Venetian marble, ad infinitum, a building that still stands and has to be seen to be believed.

One can best gauge the grandeur or Teutonic ostentation of Boldt’s vision by describing his houseboat, La Duchesse, one of thirty-one vessels he kept in his boathouse on Wellesley Island (named for Sir Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo). A building big enough to house a regimental combat team, the boathouse has slips 128 feet long.

La Duchesse is 106 feet long, has a beam that measures twenty-six feet, a net tonnage of 243, a 4.3-foot displacement, and an all-steel hull (it was originally all pine); its two stories contain ten bedrooms, five bathrooms, two open fireplaces, a dining room, and a salon. The houseboat is owned by Andrew McNally III; it serves as his summer residence and can be seen any summer day moored in McNally’s slip at Island Royal on Wellesley Island.

When Boldt’s wife, Louise, died at age forty-five in 1904, Boldt sent a telegram from the Waldorf directing 150 artisans to lay down their tools. Although he would continue to return to the islands, Boldt is said to have never again set foot on Heart Island; he allowed his dream to fall into ruin, its interior marble walls given over to poets of graffiti.

On the other hand, one of the local guys, my buddy Mike Bresnahan Sr., owns what in my opinion is the loveliest island on the river. Unlike our summer people, who name their islands things like Fairyland, Mike, whose island is number ninety-two among the islands, calls his Number Ninety-two. Fairyland indeed!

On the island of Lanai, Hawaii, where I often spend a few months with a guy I went to kindergarten with in Watertown, I’ve had my host’s angler chums from Honolulu rolling around his kitchen floor in laughter, choking out, “But that can’t be true, that can’t be true.” All I am telling them, strictly deadpan but with a storyteller’s natural elaborations and denouements, are tales of the Bay’s lawlessness, our utter disdain for seeking legal remedies, and how you learn—or had better learn—early on to mind your p’s and q’s or find your house leveled by fire. Should you drift to the outermost limits of a’s and z’s, you might find your house leveled with you in it.

In 1972 I came back to the river to live for the first time since entering college in 1948. As soon as it was established that I was Earl Exley’s son (because he was one of the few guys who could handle it, my dad had always refereed the annual bloodbath called the Bay-Clayton football game) and that my great-grandfather, John Champ from Wantage, England, had been the grounds keeper at the Hotel Frontenac on Round Island, his wife Fanny (née Maguire from Blarney, County Cork) a cook and a domestic there, everyone became as cozy with me as if I’d never been gone.

Unfortunately, a guy who’d done one too many tours in Nam came home and, without inquiring who I was but learning only that I was a writer, which to the Green Beret mentality is equatable with being a pederast, made his way down the barroom one night and tapped me on the shoulder. When I turned, he planted one full on, tongue and all. A fight ensued; I was beaten up. Later I was surprised that whenever I ran into this vet he kept his distance and was polite to the point of deference.

Two years later I learned what had happened. A friend of mine, a very, very bad dude to have against you, sought out the vet in a local bar. Explaining to him that he, the vet, had twenty years on me, that I hadn’t worked with my hands since I’d done construction work preparing for high school football, the bad dude told him he was a coward. The veteran was then strangled until the blood drained from his face; he nearly passed out and was thrown out onto the street with the admonition that if he ever put his hands on me again he’d be dead. Who needs cops?

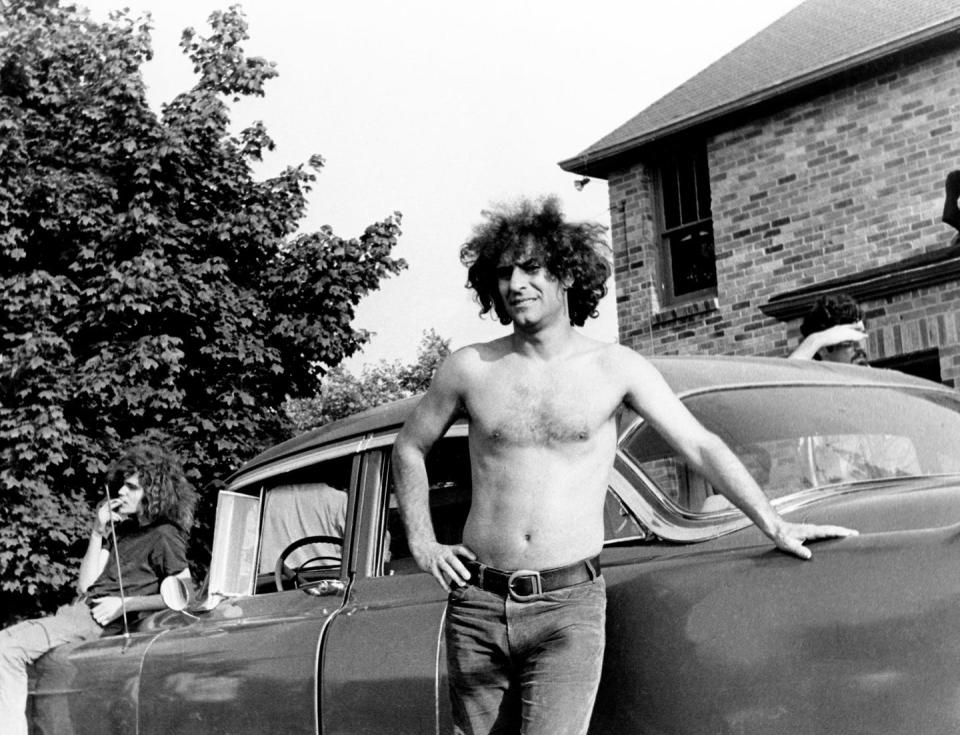

Activist Abbie Hoffman, fleeing a dope indictment, was able, with only a nose job and the aka Barry Freed, to “disappear” into our midst for four years before he chose, on the occasion of the publication of his book Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture, to surrender to the authorities. Because whispers of his true identity were circulating, Abbie surrendered himself at exactly the right time. Had he come here and stuck to tending his vegetable garden behind Johanna Lawrenson’s summer home on Wellesley Island, he could have stayed forever without any local giving a damn.

But agitation is Abbie’s life elixir; he arrived and in 1978 organized a group called Save the River, which was concerned, and rightfully so, that winter navigation—with its icebreakers—through the St. Lawrence River’s narrow channels past our islands might well destroy what the Indians of the Iroquois nation had aptly proclaimed Manatoana, “the Garden of the Great Spirit.” Although I find Abbie to be very bright, very funny, charming, a great cook into the bargain, and do in fact consider him a friend, he has so many blind spots, which may after all be the secret of effective activism, as to be damn near clownish.

For example, Abbie was constantly baiting the man I consider the most powerful in the county. I tried to explain to him that this gentleman had a summer home on one of our islands, that the man’s wife was a staunch conservationist, that the man was certainly aware of the millions in revenue these islands brought into the county, and that if there were any chance of winter navigation of the Seaway’s wrecking the islands and their surrounding fishing grounds (considered among the best northern pike, bass, muskellunge, and bullhead waters in the world), then the man would decide winter navigation wasn’t for us.

When I suggested to Abbie that he call the man, ask for twenty minutes of his time, put on a necktie, and go into Watertown and state his case, Abbie laughed in my face. That would have been too simple. Abbie and his followers had turned Save the River into a growth industry. They had their little gallon jars, in which one could deposit one’s bar change, all over the Bay; they had their fundraising lawn buffets and dinner dances, their boring lectures. To me, they were just a bunch of sillies whistling into elephant behinds. Two years ago Abbie left to take up yet another cause, in New York City, and one day in June his picture made the front pages of both the Post and the Daily News, Abbie’s thing.

After Christianity was introduced to the Iroquois, there sprang from that noble, imaginative Indian nation my favorite of the many island legends. When God summoned Eden to heaven and the garden was in its ascension, borne up by a group of white-robed angels, a thousand flowers fell from its abundance, settled on the narrow channel of the St. Lawrence between the U. S. and Canada, and became our islands.

If Alexandria Bay and the islands could not be Eden for most people, they have in many ways proved to be so for me. You, as is the case with most of our summer people, could not make it through one of our eternal winters and would sit in the Dock Side in a state of benumbed queasiness as guys argued about the best way to cook “rat.” They would be talking about muskrat, or musquash. Although a member of the rodent family, the rat is a vegetarian, a grass feeder; and parboiled for a short time, then simmered slowly in oil and fresh garlic, it has a less gamy taste than lamb.

The bullhead is of the catfish family, but were you to compare it with that dry, white-fleshed, tasteless creature they are now “farming” down south for supermarket and restaurant consumption, you would get laughed from the room. Most locals here would eat spring bullhead above any other fish, then northern pike, then smallmouth bass. Although many members of the Bass Anglers Sportsman’s Society consider the islands the best grounds in the world, in their tournaments here they are after weight, and they end with an allowed daily culled catch of five largemouth bass. Unless you insisted on keeping your bass, our guides would return a largemouth to the river.

In my youth I hunted and fished. I no longer do either, which is not to say that when Jimmy Duclon, whose father and grandfather guided on this river before him (as will his son Danny after him), prepares his annual February game feed of rat appetizer, fish chowder, venison stew or venison steak, and tossed salad with—what else?—Thousand Island dressing, I’m not first in line, clanging my knife and fork like a stir-crazy inmate in those “big house” movies of the Thirties. In summer I spend a lot of time on the river, but I never go with a skipper whose habits I don’t know. And because I can’t afford a boat and hence have to wait until someone is returning to the Bay, I never, never go to a social function on an island.

Five or six times a year I call Uncle Sam Boat Tours and, when Captain Chuck Scott is going out, stroll the three minutes to the public docks, go up on the upper exposed deck, and take the two-and-a-half-hour trip. There was a time when I plugged my ears with cotton so I didn’t have to listen to the spiel about the lovely island and summer residence to our left being owned by the socially prominent attorney John Dinglenuts of Dingleberry, Virginia, a clown we locals knew to be prominent only in the way breaking wind can lend prominence in a crowded chapel. Recently, however, I find I can tune out both the announcer and the “cottages” and view the islands as the Iroquois saw them.

In season I am in bed at 7:00 P. M., sleep until midnight, when the bars start closing and the noise begins to cease, then go to my studio-office above the Dock Side, watch the late movie on Ottawa 6—tonight it was Astaire and Cyd Charisse (what guy who grew up on Cyd can ever forget her?)—and read and work until eight, when I tee off at the municipal course (my best score? Thirty-eight for nine holes, 83 for eighteen). On Labor Day, when I resume a normal schedule, guys ask if I’ve been away for the summer and I tell them yeah. My entire social life here is circumscribed within the length of a football field, with the Ship Restaurant on the east, the Dock Side at midfield, and Cavallario’s Steak House off in the western end zone.

When the late George “Bud the Bear” Hebert, by consensus one of the nicest men who ever came through this village, as well as one of the biggest characters, was alive, I used to go to his Edgewood, one of the best resort complexes up here. The Bear used to tell me that as long as I took care of my tips I could charge whatever I wanted.

When I’d go to pay, however, there was never any bill, and one day his bookkeeper, Betty Blount, now, alas, also dead—too young, too young—told me that whenever a dinner or bar check of mine came across the Bear’s desk, he’d growl and say, “Exley ain’t got any money,” tear the check up, and throw it in the wastebasket—this, mind you, after insisting that I charge whatever I wanted and constantly reminding me that if I needed anything I shouldn’t hesitate to ask. In embarrassment, I of course had to stop going there.

Concetta (née Sparacino), my high school classmate, and Frank Cavallario own the Steak House (always jammed in season); Vince and Frank Rose, the Ship (also jammed); and Mike Bresnahan Jr., with whose father I played high school football, the Dock Side and also the busy sidewalk café, Admirals’ Inn, which I can see from my studio window. None has ever presented me with a bill. When recently, for example, I had a slight windfall and went to settle with them, their attitude seemed to be, “I don’t give a damn, Ex, gimme what you can.” It was as though as a writer I were a special person, and not special in the way James Joyce’s genius was special but as though I were not quite right or stable and ought in fact to be in training for the Special Olympics.

More than anything, of course, they (my paranoia wonders if “they” conspire) were telling me that I had no excuse whatever for not finishing the final volume of the trilogy I’d started twenty years before, that they were providing me with a Yaddo not of box lunches but, were I so inclined, which I’m not, of top-shelf Scotch and prime ribs of beef. The thing is, however and after all, there is simply no book I can give them that can in any way compensate for their faith that I’d complete what I’d started out to do. It is as though—oh, crippling, abominable thought!— they are saying, “You have made us a promise, tacit though it is, Ex, and we expect you to keep it.”

You Might Also Like