‘Lost in this Evil’: The police code of silence claims a cop on the Bayou

Corrections & clarifications: An earlier version of this story misstated the rank of a former New Orleans Police Department member who is now on death row. He was a police officer.

On the afternoon of May 2, 2013, Baton Rouge police kicked in the door of 6349 Flag Street, a faded blue shotgun house set atop cinder blocks and surrounded by a chain-link fence and scorched grass. The neighborhood, an unincorporated sliver east of Airline Highway, is almost entirely Black. One in three live below the poverty line. There are a couple of churches, a dollar store and a high school spread among the low-flung homes.

Fifteen narcotics detectives and patrol officers — foot soldiers in America’s Sisyphean war on drugs — were looking for a local man who, one informant had assured them, was trafficking crack cocaine and armed with an assault rifle.

Police in SWAT gear stormed the house. Neighbors gathered along the fence, blocked by a phalanx of cops. They heard a commotion from inside, then muffled screams, then nothing.

Less than 15 minutes after police went inside, paramedics came out with a 32-year-old Black man on a stretcher and loaded him into an ambulance. The man’s mother looked on from behind the fence, shocked and confused, pacing back and forth as she begged for one of the officers to explain what had just happened. She received no answers.

Around 2 a.m., a local television station reported a statement from the Baton Rouge Police Department: A man “was in distress” after swallowing drugs when detectives arrived to execute the search warrant and he had died. “No foul play is suspected,” the sheriff’s office said.

Police did not announce what their raid had yielded from the house that day: one marijuana blunt, two cell phones, $231 in cash and “one small suspected crack cocaine rock.” The critical facts about what happened in those 15 minutes were held close by police and would go unexplained for years.

The narcotics officers who had answers knew better than to speak about them publicly. But in private conversations at police headquarters, in jokes among those who were in the house, that day had a name:

The Flag Street Massacre.

Help USA TODAY investigate law enforcement’s code of silence

USA TODAY is documenting how law enforcement agencies around the country threaten and retaliate against internal whistleblowers who expose misconduct by their fellow officers. If you have a story about that or know someone who does, we want to hear from you.

The weeping prophet from Baton Rouge

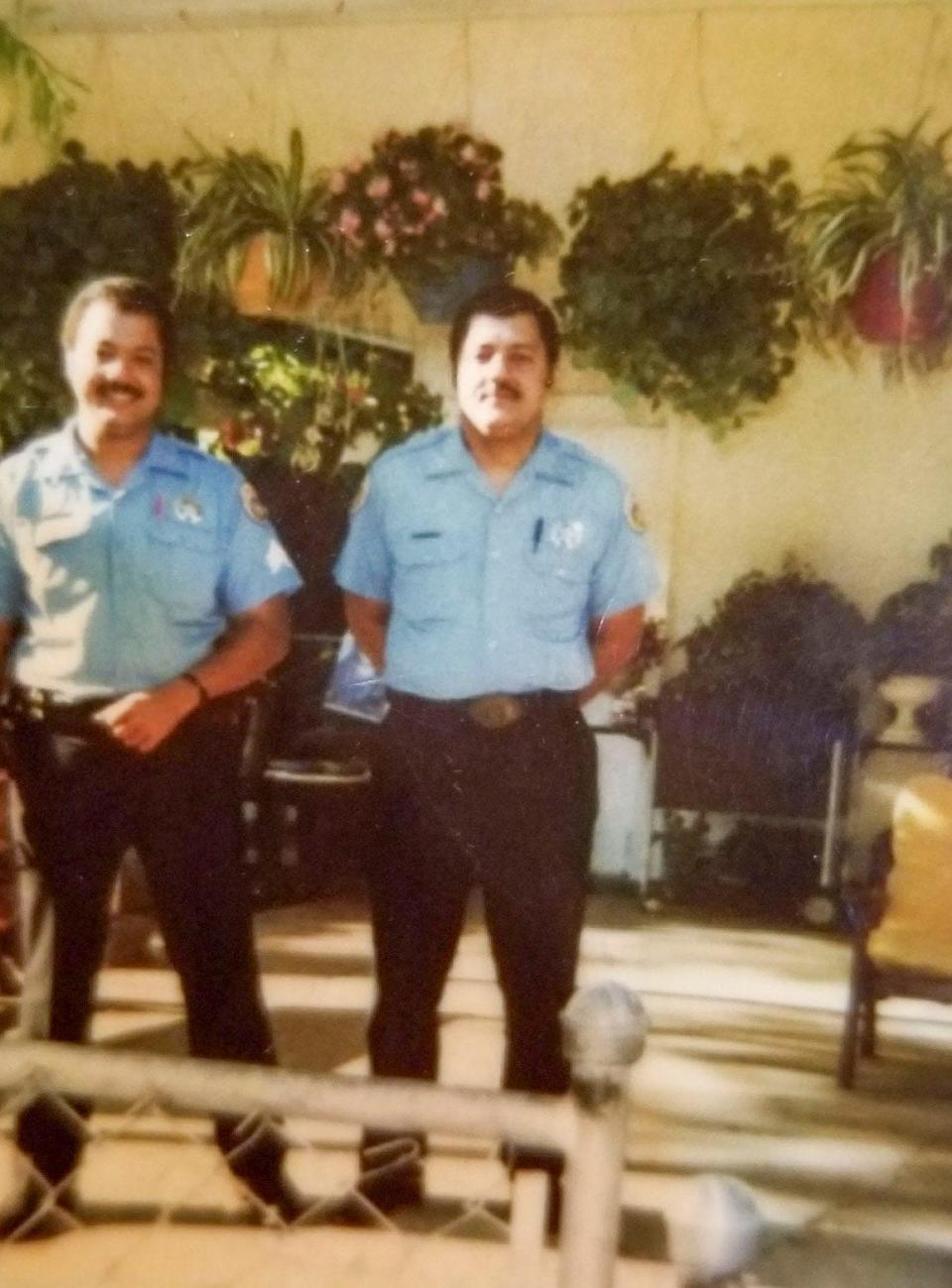

Jeremiah Ardoin is the son of a sheriff’s deputy and an oilman. His mother Annette wore the badge and his father Horace was a technician inside one of the refineries that rise above Louisiana’s bayou with bellowing smokestacks and lights like skyscrapers.

They named Jeremiah after the Old Testament “weeping prophet,” who warned that Jerusalem faced destruction because of the sins of Israel’s high priests and kings. The prophet is known for having the courage to deliver unwelcome news even though he was reluctant to do so.

Jeremiah grew up in 1980s Baton Rouge, the Deep South capital of Louisiana, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. The city is steeped in segregation and tension among the mostly Black population and mostly white police force.

In the decade before he was born, civil rights demonstrations at Southern University in Baton Rouge turned deadly when police killed two unarmed Black students. Afterwards, in 1980, a federal civil rights investigation found the Baton Rouge police department was discriminating against Black people looking to become cops. The U.S. Department of Justice issued a consent decree to force the department to diversify.

After Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, out-of-state troopers who came to help with recovery efforts quickly left the state after witnessing rampant racism and misconduct in Baton Rouge law enforcement. They said officers there harassed Black citizens who had fled from New Orleans, wantonly sprayed mace into crowds, went into homes without warrants, and in one case offered to let a visiting trooper beat an inmate as a thank-you gift.

More recently, in 2016, Baton Rouge police shot and killed Alton Sterling, a Black man selling CDs. Protests enveloped the city. Less than two weeks later, a gunman ambushed and killed three officers, wounding another three.

The fraught relationship between the people and those who police them is as much part of Louisiana’s DNA as the oppressive humidity.

In such an environment, Jeremiah’s parents raised their three children to be self-sufficient. Horace taught them how to hunt. Annette taught them to cook. They steered their kids clear of the street by sending them to private elementary and middle schools.

In high school, Jeremiah told his mom he wanted to follow in her footsteps and enlist to be a police officer. “I’ve wanted this all my life,” he said. Annette quit smoking the day he graduated from the academy in 2008, a bargain she made with God to keep her boy safe on the job.

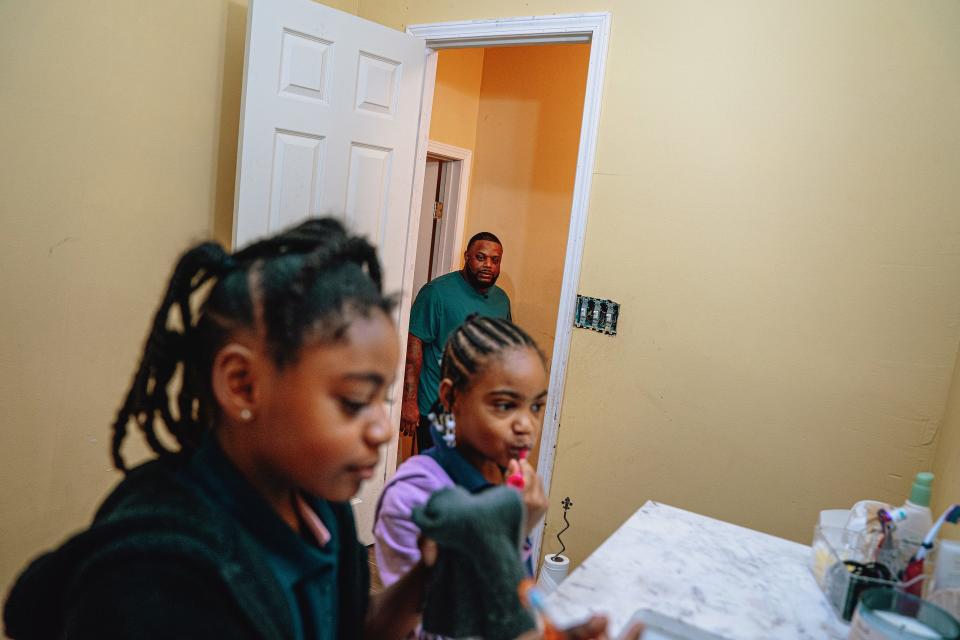

Jeremiah went to work for the Baton Rouge Police Department. The uniform was a tight fit around his barrel chest. His arms are roped with tattoos showing the Freemasons symbols and his four children, including a baby girl who died hours after she was born.

By 2013, he was five years into the job with a house in Baker, a small suburb that borders the northern edge of Baton Rouge. He was making $80,000 a year and started investing in livestock that he butchered and sold to neighbors. Goats, chickens, pigs and turkeys plod through mud in his backyard, vying over patches of shade to keep cool.

On May 2, 2013, the day his colleagues kicked in the door on Flag Street, Jeremiah was working a detail at Baton Rouge General Medical Center. At 5:21, paramedics rushed the 32-year-old Black man they’d pulled from the blue house through the emergency room doors, flanked by multiple narcotics officers. The man on the gurney was Dontrunner Robinson.

Jeremiah looked down at Robinson and saw a mash of blood and swollen flesh, with an open gash the size of an apple slice above his left eye. His upper body was mottled with bruises. Too many to count.

Police told doctors that the bedroom door had hit Robinson’s face when they kicked it in.

In the moment, Jeremiah did what’s expected of police in situations like this: nothing.

State secrets

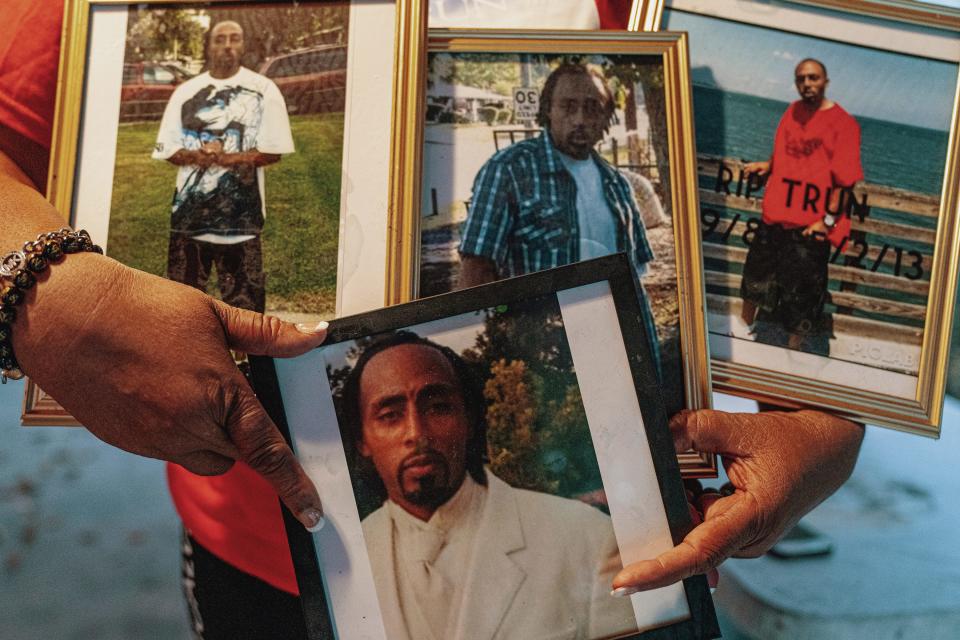

After the paramedics took her son from Flag Street to the hospital, Casa Robinson Bean left the chain link fence and drove off to pick up Robinson’s 2-year-old — her grandson — from daycare. Casa, a God-fearing woman who calls everyone “baby” and swallows up near-strangers in hugs goodbye, didn’t want the boy to be with anyone else.

On the way back from the daycare, a family friend called from the hospital: Dontrunner’s dead. Casa pulled over and wept until she was out of breath. She climbed into the backseat with her grandson.

“I just held him for a minute,” she recalled.

Casa found a frenzy of neighbors, kin and family friends waiting for her at the hospital. The officers there would not let Casa see her son’s body before they sent him to the coroner. It’s evidence, they told her.

Casa sent her brother-in-law, Lester Ricard, a pastor, to the funeral home to identify the body. If the swelling hadn’t gone down by the time he arrived, Ricard said, he may well have not recognized his nephew. He spoke with the mortician, who explained how much work it would take to prepare Robinson’s face and head for an open casket funeral.

“The family already went through enough,” Ricard replied. The funeral was a closed casket.

Casa had only clues about what happened inside the house on Flag Street. Robinson’s widow Alaysha had been in the bedroom. There, Alaysha said, four officers barged in and pounced on her husband before repeatedly punching him in the face and chest. Where is it? they barked. One officer struck Robinson with the butt of his rifle and dragged him off to the living room, according to Alaysha. They turned over furniture, cushions and drawers throughout the house.

Photographs the family took of the scene afterwards show blood smeared on the walls and door jambs, and pooled on the tile.

Casa and Alaysha filed a wrongful death lawsuit in 2014 against the city of Baton Rouge and the officers who raided the house on Flag Street. But the case languished. Their attorney didn’t file motions to move the case forward for more than three years.

In court, Baton Rouge attorneys denied that the officers on the raid did anything wrong. “At no time was Dontrunner [Robinson] beaten, kicked, or abused,” they said in one filing. “No deadly force was ever utilized." After three years, a judge agreed to dismiss the suit after the city argued the family’s attorney had abandoned it. (It is still officially pending.)

Casa and Alaysha learned virtually nothing about Robinson’s death. They said the East Baton Rouge Sheriff's Office — which conducted an investigation of the incident — and Baton Rouge police did not release any records to the family or the public. Casa and Alaysha hoped to hear from the state attorney general or maybe even the FBI to tell them they were looking into possible civil rights violations. But the calls never came.

Eight years later, Casa struggles to understand how other cases of police brutality and in-custody deaths garnered nationwide protests and reform efforts while she couldn’t get basic information about what happened to Robinson. George Floyd was painted on city streets and Tweeted by professional athletes. But nobody outside her family and the neighborhood east of Airline Highway seemed to know her son’s name.

***

Across Louisiana, mothers and other loved ones seeking answers have been on the wrong side of police secrecy for years. When I visited last summer, word spread through an unofficial network of grieving families and local activists that a reporter was looking into some cases. They hoped an outsider might be able to shake loose new evidence.

Tara Snearl said she can’t find anyone at the Port Allen police department willing to discuss her son’s cold case homicide or the bungled investigation that followed in 2017. “They won’t even tell me who the lead detective is,” Snearl said.

The department refused to release investigative files. A Port Allen police official emailed that the chief “is declining all interviews” concerning the case.

Breka Peoples, a local activist in Shreveport, said the police department is covering up multiple in-custody deaths and at least one rape in the back of a patrol car. Families are left with little recourse. “They don’t have anywhere to turn,” Peoples said. “And no one is held accountable.”

Earlier this year, the Associated Press published videos showing Louisiana State Police troopers beating, stunning and dragging Ronald Greene, an unarmed Black man, after a car chase in 2019 outside Monroe. “I’m sorry,” he pleaded, blood splashed on his skin and clothes. “I beat the ever-living f--- out of him,” one officer said in an audio recording. Greene stopped breathing soon after.

For almost two years, troopers lied to Greene’s mother, Mona, by saying her son had died in a car crash. They had refused to release the videos revealing the truth.

“We’re lost in this evil,” she told me recently.

The episode and the coverup that followed were particularly alarming considering the agency’s role. When there’s an in-custody death or deadly shooting, local Louisiana police departments often rely on the State Police to find out what happened and determine whether officers were at fault. Since the Greene scandal broke, critics have argued the agency is not equipped to hold itself accountable, let alone others.

Carl Cavalier was one of a cohort of troopers inside the State Police who worked to leak information about Greene’s killing. He collected emails and other documents showing the department brass blocked internal investigators when they wanted to arrest one of the troopers responsible.

Cavalier went public this summer and sat down for local TV interviews, in a suit and bowtie, to explain the documents. He has since filed a lawsuit against the department, alleging discrimination and retaliation.

Federal prosecutors are now probing whether State Police leaders obstructed justice to protect the troopers, as well as the abrupt disbanding of an internal panel that was supposed to be investigating other incidents of excessive force against Black motorists.

In the meantime, State Police commanders suspended Cavalier and sent him a letter saying they intend to fire him for disloyalty to the department and for making unauthorized public statements, among other infractions.

I met Cavalier for lunch in New Orleans in June. He had been using a pseudonym over the phone, Elijah Steele, the name he used during undercover operations, because he was wary of outsiders connecting his name with the department’s leaks. He showed up to the restaurant two hours early to make sure nobody was watching or listening.

Cavalier told me he leaked information about the Greene case because the oath he took when he became a police officer requires him to help a mother in distress like Mona.

“I didn’t seek this trouble out,” Cavalier said. “I deserve to keep my job.”

Lamar Davis, who was appointed State Police superintendent in October 2020, said the Greene scandal prompted a raft of reforms, including bystander intervention training and quarterly reviews of bodycam footage. “I’m not one that believes in covering up and that blue wall of silence,” he said.

Davis would not discuss Cavalier’s situation specifically. But he said he values transparency and that officers would be within their rights to report misconduct to the FBI or attorney general if they felt the internal grievance procedure had fallen short.

Most department leaders who agreed to interviews for this story said something similar: the code of silence may be a problem in law enforcement, but not in their own agencies. Yet rank-and-file cops and other officials around the state were often terrified to talk openly about police misconduct for fear of retaliation from peers and supervisors. One source insisted on meeting at midnight in an abandoned warehouse. Another left records stashed in a graveyard and on top of car tires. A private detective was sure we were being watched at a coffee shop.

Another former officer said he was so scared after reporting misconduct in 2018 that he sent his wife and children away to live with his in-laws. He installed a motion-sensored camera on his porch and slept on the couch with a rifle across his chest.

“When you come forward with this stuff and you see nothing’s happening, you start getting scared,” said Allen Ordeneaux, a former police officer in Amite. “Because this stuff is fixing to blow up in our face.”

Fire in the bones

By 2020, Jeremiah Ardoin was a veteran in the Baton Rouge Police Department and the only Black narcotics detective. As such, he spent much of his time undercover in plainclothes, a hat tucked low over his eyes with a bushy beard that covered much of the rest of his face.

Jeremiah witnessed and often participated in a years-old tactic within the narcotics division called “snapping.” In other cities, it’s known as stop-and-frisk. Detectives drove around Baton Rouge’s minority neighborhoods and accosted men on the sidewalk, without probable cause, and patted them down looking for drugs or weapons.

Donald Grim, a former Baton Rouge police narcotics detective who retired in 2013, estimated that thousands of people were arrested this way while he was in the department. They typically went out on Wednesday and Friday nights to shake down Black people standing on street corners or just walking, Grim explained. He complained to his commander about it over the years, Grim said, but he never considered breaking the chain of command and going to the chief. “They wanted everything hushed and quiet,” he said.

Murphy Paul became the Baton Rouge chief of police in late 2017, welcomed by the mayor as a progressive trying to bridge the gap between citizens and the 700 sworn officers in his department. A clean-cut and bespectacled New Orleans native who had previously spent 19 years with the state police, Paul accepted the job as Baton Rouge was reeling from the killing of Alton Sterling, the deadly ambush on officers, soaring homicides across the city and a devastating flood.

Paul fired the cop who had killed Sterling even after state and federal prosecutors declined to press criminal charges. The case had made national headlines and Paul was lauded for apologizing to Sterling’s family. In 2019, under Paul’s tenure, a federal judge lifted the consent decree imposed to fix the department’s discriminatory hiring.

On August 13, 2020, Jeremiah met with Paul and others on the command staff for a disciplinary hearing. Jeremiah had failed to file the correct paperwork after he broke a car window. Afterwards, Paul asked the detective to stick around and talk. What else, the chief asked, has been going on in the narcotics division? What can we do to improve?

Jeremiah took a beat to pick his words carefully. Cops who have chosen wrong in moments like this have come to regret it for the rest of their lives.

Without naming names or identifying specific incidents, Jeremiah mentioned the division's focus on numbers and arresting low-level drug users instead of drug traffickers.

The way Jeremiah tells it, he explicitly told the chief about the snap arrests. Paul disputes that Jeremiah ever mentioned anything outright illegal or unethical. Still, the chief was concerned about the division’s misplaced priorities on drug-possession cases. Immediately after the meeting, he told his deputy chief to fix it.

“I want our focus on violent crime,” Paul said. “I don't care about quantity. I care about quality.”

***

Within days, Jeremiah said, two close friends in the department told him that his conversation with the chief had made its way around the office. They warned Jeremiah to tread lightly after overhearing several detectives discussing his betrayal. They’re going to set you up, one friend told him.

On December 9, 2020, officers in the intelligence division executed a search warrant at Jeremiah’s home, going room to room looking for a television and door cameras, which, Jeremiah says, they had previously marked as stolen. When they found the electronics, the detectives issued Jeremiah a criminal summons, charging him with two misdemeanor counts of possession of stolen goods and criminal conspiracy.

Jeremiah says he bought the electronics as Christmas presents from a woman who was a friend of a friend. He now believes that she was a confidential informant of Jason Acree, a corporal in the narcotics division, and that Acree and others in the narcotics division set him up in retaliation for his disclosures to the chief.

John McLindon, Acree’s attorney, confirmed that Acree had told his supervisor that Jeremiah was purchasing stolen electronics on the street. McLindon said Acree was just doing his job and not looking to get back at his colleague.

Pending the criminal investigation, Paul put Jeremiah on administrative leave in December 2020. The police department has refused to release documents concerning the stolen electronics charges. The parish court has no record of the case either. All Jeremiah received was the one-page summons.

The criminal charges weighed on him. Jeremiah called Ron Haley, a young civil rights attorney with blue suits and a silver tongue, who told the detective to write up memos detailing the misconduct he’d witnessed during his tenure at the department. Haley planned to give the memos to the department, evidence of wrongdoing much larger than one officer.

Jeremiah sat down at the desk in his house and started typing. A ball python watched from a glass case above the computer. When Jeremiah the prophet spoke out about the sins of the other high priests in ancient Jerusalem — those words like “a fire shut up in my bones” — they conspired to kill him.

But at that moment, Jeremiah wasn’t thinking about biblical retribution. In fact, he thought few people would pay much attention to what he had to say.

‘Silence is complicity’

He wrote the title in all caps, “BRPD NARCOTICS CORRUPTION.” Underneath, Jeremiah spilled a litany of sins within the department, incriminating his colleagues.

Over two letters eight pages long, Jeremiah accused Acree of stealing drugs and money out of the evidence locker and from crime scenes. He explained the “snap arrest” program and the countless times he saw people stopped without probable cause. He said officers planted drugs on people. Jeremiah wrote that Sergeant Drew White liked homicides because it meant that he’d get more overtime money.

Jeremiah described the aftermath of his meeting with the chief months earlier: “I contacted BRPD Administration as a whistleblower where I was then immediately targeted by BRPD Narcotics.” The division’s leaders “attempted to crucify me,” he added.

Jeremiah explained why he decided to come forward in the first place: “Silence is complicity.”

“I got tired of hearing them wishing more black and brown people in the community would die so that they could fill their pockets,” he wrote. “Because I got tired of hearing them laughing and joking about how Drew White killed, Dontrunner Robinson, an unarmed black man, by beating him to death with his hands and pistol, which they called the ‘Flag St. massacre.’”

White and other officers were cleared of misconduct in the Flag Street case after a 2013 internal investigation. Jeremiah himself walked back the allegation in interviews with local reporters afterwards to say he just wanted to bring attention to how officers were joking about the case.

White did not respond to requests for comment. His lawyer, Kyle Kershaw, who also represents the police union, said Ardoin is no whistleblower.

“It is amazing,” he said, “that some would now consider him a bastion of veracity for attempting to tarnish the reputations of his former fellow officers and the Baton Rouge Police Department subsequent to his arrest.”

Still, Jeremiah’s memo mentioning Flag Street was the first time in almost eight years that any officer had spoken publicly about Robinson’s death. His disclosures sparked a local media firestorm. Paul suspended the narcotics unit’s operations and reassigned four supervisors to street patrol, including White. Internal affairs opened up investigations into the officers Jeremiah named in the letters. One resigned and another was fired, Paul said.

The department arrested Jason Acree in February 2021 on charges that he had stolen drugs from the evidence locker. He was arrested again after State Police troopers caught him drag racing on the interstate with painkillers and three guns in the car.

Prosecutors have charged Acree, who resigned from the department, with perjury, drug possession with intent to distribute and malfeasance in office. He’s pleaded not guilty.

Paul launched audits into the old cases of Acree, Jeremiah and several others in the narcotics department. Those audits are still ongoing. Paul said the department uncovered two dozen cases in which Jeremiah documented seized drugs that are now unaccounted for. Jeremiah has not been charged for any of those cases.

Paul said he also contacted the FBI and the district attorney’s office about the allegations in Jeremiah’s letters. Following pressure from lawmakers and the Baton Rouge chapter of the NAACP, the district attorney, Hilar Moore III, has purged more than 600 criminal charges that the narcotics unit had brought against civilians dating back years. It’s one of the largest shakeups in the history of the Baton Rouge Police Department, one that could impact prosecutions, appeals and criminal investigations for years.

A group of defense attorneys recently found thousands of other potential charges in which a disgraced Baton Rouge narcotics officer was involved. They are now trying to spring 75 of those defendants from prison. “This is a mess like none that I’ve seen,” said David Utter, one of the lawyers leading the effort, known as the Fair Fight Initiative.

As far as Jeremiah knows, Moore has not dropped the stolen electronics case against him, even though Acree initiated the investigation.

Paul maintains that his administration acted appropriately when Jeremiah disclosed misconduct and said he appreciated the detective speaking out. “We would not have known what we know had he not come forward,” Paul said in a recent interview. “When we don't speak up it hurts us as a profession.”

But, he added, Jeremiah’s plight is not a case of coordinated retaliation against a whistleblower. “I can tell you this,” he said, “we investigated his complaints just like we investigated the complaints against him.”

***

While Acree was under investigation for the allegations in Jeremiah’s memos, he told internal affairs investigators that he found heroin in Jeremiah’s patrol car. Two other officers told investigators they found marijuana in the car, as well.

Jeremiah was stunned. “They planted drugs on me,” he said.

The Advocate later reported that a separate internal investigation found no evidence of drugs being planted on Jeremiah. Acree was arrested for stealing drugs days after he said he found drugs in Jeremiah’s car.

Jeremiah was on administrative leave — suspended pending the outcome of the stolen electronics charges — at the time he was told about the new administrative investigation into him over the drug allegations. Jeremiah has not been charged criminally for it.

Jeremiah feared for his family’s safety. He installed cameras in his car and his fiancee’s. He started driving around Baton Rouge instead of through it. He got a guard dog for the driveway.

On April 27, he resigned from the department.

“I cannot continue to successfully serve the community of Baton Rouge,” Jeremiah wrote in his resignation letter, “while in a work environment where I must constantly watch my back in fear of retaliation.”

‘It’s even worse today than it was back then’

Mary Howell works out of a purple and white Victorian house in mid-city New Orleans with flowers painted on a sign out front that reads “Law Office.”

For more than 40 years, she’s represented victims in some of the most infamous brutality and corruption cases in the history of Louisiana law enforcement, many of which police leaders tried to cover up. “A blue curtain exists … to a greater extent in New Orleans than in most cities,” a federal appeals judge said during one of Howell’s cases in 1980.

Howell, one of the country’s most accomplished civil rights attorneys, is an expert on the code of silence in Louisiana, arguably one of the worst states in the country to be a police whistleblower. She’s amassed banker boxes full of court files and news clippings from virtually every instance of police wrongdoing in the state going back decades. She once sat on a panel at a law enforcement conference called "How to blow the whistle and live to tell about it.”

This is a literal concern of hers based on experience.

On the far wall inside Howell’s office is a portrait of Kim Groves, a citizen who filed a brutality complaint against a New Orleans police officer in 1994 after she saw him beat a teenager with his baton. The officer hired a hitman to execute her. Howell represented the Groves family in a lawsuit that lasted almost 23 years before settling in 2018 for $1.5 million. The officer was convicted in 1996 and is now on death row.

After Hurricane Katrina made landfall in 2005, police officers opened fire on unarmed Black civilians wading through the water looking for shelter by the Danziger Bridge. They killed two and wounded four others. One of those killed was Ronald Madison, a mentally disabled 40-year-old man, shot seven times total — five in the back. Howell represented his family in a lawsuit against the department.

Danziger Bridge became one of the most notorious incidents in New Orleans’ history and a symbol of how many police officers turned on Black citizens when they were most desperate for help. Some in the department tried to conceal what had happened by claiming that the shooting was justified because the officers were under fire. We don't want this to look like a massacre, one supervisor said during a meeting afterward.

U.S. District Judge Sarah Vance, who presided over the criminal trial of five officers involved, said: "I don't think you can listen to that account without being sickened by the raw brutality of the shooting and the craven lawlessness of the cover-up." All five officers were sentenced to prison.

In December 2016, the city settled the Danziger Bridge lawsuits, along with two other cases, for a total of $13.3 million. The mayor at the time issued a rare apology. “There are some individuals,” he said, “who do the wrong thing for the wrong reason and make it worse by either denying it or covering it up.”

***

On a damp Saturday afternoon last July, I sat with Howell on her patio to talk about the culture entrenched in law enforcement that inhibits so many police officers from speaking out against fellow officers. In her lap was a stack of homework assignments — studies, news articles, court transcripts and one book. She often punctuated a thought by passing me reading material.

The common thread in many of the cases we discussed was an officer or two who thought they were doing the right thing but then found themselves up against departments who turned against them. "The power of these voices is as strong as the urge to silence them," Howell said.

Many of those who sought outside help found none. It’s not uncommon for state and federal officials in Louisiana to ignore whistleblowers altogether or start and then abandon investigations only after people expose themselves.

I told Howell about Jeremiah Ardoin in Baton Rouge and the fallout he faced after coming forward about misconduct in the narcotics division. She said it’s a common playbook. "To ask people to step out is to ask them to commit career suicide,” she said.

There are cautionary tales all over the state.

In Orleans Parish, a jailer secretly photographed the bloody jail cell after a 2012 stabbing, which the sheriff’s office had misrepresented as "superficial cuts.” The jailer gave the pictures to civil rights lawyers and local news reporters, which helped lead to a federal consent decree after a judge determined the prison conditions were unconstitutional. The sheriff launched a criminal investigation into the jailer because he broke policy by using a cell phone to take the photographs.

In Amite, the police chief discovered two of his officers cooperating in an FBI probe — “covert FBI collusion,” the city attorney later called it — into the department’s brass, including the chief. He fired one for not informing him about the investigation and the other for accidentally mislabeling two evidence bags in an unrelated case. The city told state unemployment officials that the officers didn’t deserve benefits. “You are doing what's right,” one of the former Amite officers, now an electrician, said. “But yet you're being persecuted as if you did the wrong thing.”

In Eunice, a police lieutenant filed a retaliation lawsuit against the department this past June, claiming the chief opened a “bogus criminal investigation” into him after he reported fellow officers who had punched, choked and dragged handcuffed suspects during multiple incidents. The lieutenant said the district attorney required the chief’s permission to investigate anyone in the department and informed the chief that the lieutenant had reported misconduct to prosecutors. Afterwards, his fellow officers instructed an inmate to falsely accuse the lieutenant of soliciting bribes, “so they can get rid of his ass,” according to the inmate's testimony.

In Jennings, an internal affairs investigator wanted to pursue criminal charges against an officer's “unprovoked and unjustified” shooting of a dog, an incident that was caught on a bodycam video. But the mayor said no. The investigator filed a complaint with the State Attorney General’s office and called three times to follow up. She said nobody returned her calls. The investigator ultimately quit and left the state. (In a statement, city officials said the officer who shot the dog was fired and the district attorney found “no criminal action on the part of the Jennings Police Department.”)

In Iberia Parish, jail deputies pleaded guilty in 2016 to pummeling Black inmates in the prison chapel, where there was no camera. On at least one occasion, an officer made an inmate simulate fellatio on a baton after beating him. The deputies coordinated to lie about it later. “You don't rat out your fellow officers,” one testified during the sheriff’s criminal trial. “You turn the other way, and you just mind your own business.” The sheriff, who denied knowing about the abuses, was acquitted. Afterwards, he said the deputies who testified against him had "betrayed my trust.”

In Harahan, at least three officers in recent years were fired after they reported botched drug investigations, a gun missing from the evidence locker and that an officer falsified charges against a Black resident. In response to those disclosures, the officers have argued, Chief Tim Walker fired them.

“You named people you believe are in on the cover up," Walker wrote in one termination letter, “even possibly ME."

Whistleblowers like these are rare, Howell explained, because most officers are passive in the face of misconduct. Bystander intervention training, like the EPIC program she helped implement in New Orleans in 2014, redefines loyalty to mean that officers who don’t stop or report misconduct are doing a disservice to their fellow officers. These programs, which are gaining popularity in other cities, are designed to prevent incidents from happening in the first place so there wouldn’t be a need for a whistleblower later.

But as it is now, police departments often make an example of whistleblowers to warn others about meeting a similar fate. “Instead of changing a corrupt culture,” Howell wrote in an email recently, “they are often victims of it.”

***

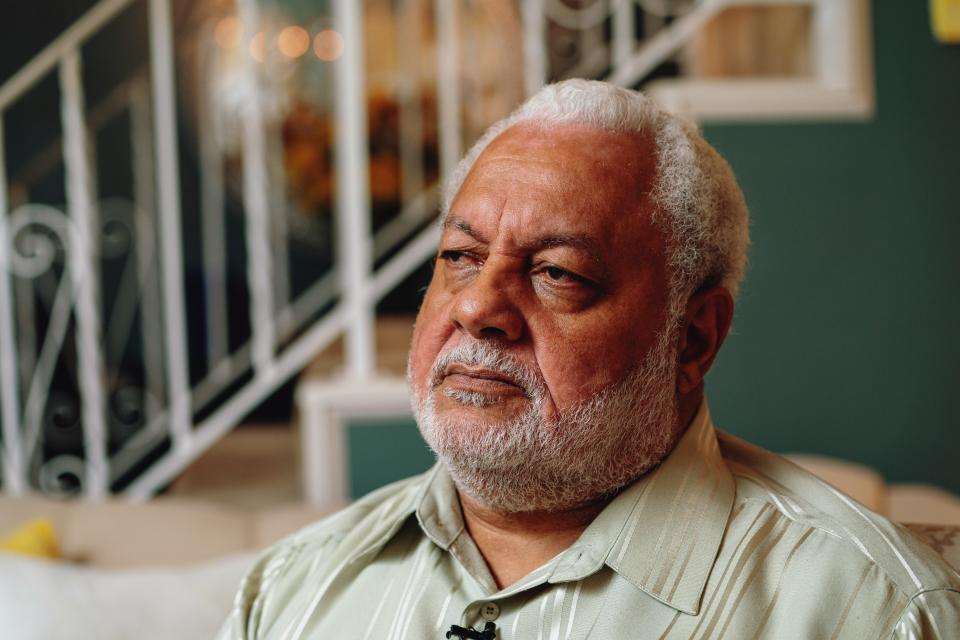

Two such people she often mentions are Randolph Thomas and Oris Buckner — perhaps Louisiana’s oldest living police whistleblowers.

In 1979, Thomas, then a New Orleans police officer, refused to sign arrest warrants after he saw his partner crack a suspect’s skull with a baton and then lie about it in the report. Thomas was investigated for refusing to obey orders, suspended and then fired.

Thomas sued for wrongful discharge and won. The jury found there was a conspiracy to shun Thomas and push him out of the department. The court ordered the department to reinstate him.

Thomas, now 66 and living in Houston, where he works as a security guard at the airport, keeps his frustration and ire close to the surface. He gets exasperated talking about what happened to him in New Orleans and how it’s echoed through generations of law enforcement. “By staying quiet you are condoning what happened,” Thomas said.

He mentioned how three other Minneapolis police officers stood by while Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd and then gave statements afterwards justifying Chauvin’s actions. That, to Thomas, was unconscionable. “I believe it's even worse today than it was back then,” he said of the culture of silence in police departments.

Buckner now lives down the street from Thomas in Houston. The two are close friends.

Buckner cooperated with federal prosecutors, in exchange for immunity, during the infamous New Orleans “Algiers Seven” investigations. In 1980, after an officer was shot dead, a group of city homicide detectives looking for suspects reportedly shot and killed four Black residents. Others said police beat them with phone books, put plastic bags over their heads and performed mock executions during interrogations.

Federal prosecutors indicted seven officers and three were ultimately convicted of civil rights violations. Prosecutors said that without the testimony of Buckner — a Black detective who admitted to participating in one of the beatings — everybody would have gotten away with it. Nobody was ever charged for the four deaths.

Though the Algiers Seven case is part of the city’s dark lore, the fallout for Buckner went largely unreported. He said his family received threatening phone calls. They were followed by unmarked police cars. He said he was passed over for promotions he was qualified for.

A friend and fellow officer told Buckner something he still carries with him: Buck, I see what you’re going through. I’ll never open my mouth.

The Flag Street Massacre

Casa Robinson Bean had given up hope that she would learn what happened to her son inside the house on Flag Street. But this past April, Eugene Collins, the ubiquitous local NAACP chapter president, told her a narcotics detective named Jeremiah Ardoin had divulged new information about the case and other misconduct at the Baton Rouge Police Department.

Casa’s head spun with the idea she might finally get some answers. But the Baton Rouge Police Department refused to release any records from its 2013 internal investigation into the raid because that inquiry “resulted in an exonerated finding for each officer involved.”

But other records shed some light, for the first time, on how a major drug raid produced little more than a dead man and a lot of unanswered questions: a second investigation into the case conducted by the East Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Office, which was the outside agency charged with investigating Robinson’s death; Baton Rouge police incident reports detailing officers’ accounts of the raid; records from the hospital and paramedics noting Robinson’s injuries; and an autopsy report from the coroner’s office with the pathologist’s determination of Robinson’s cause of death.

Taken together, the documents reveal significant discrepancies in the official narrative Baton Rouge officers gave to explain Robinson’s blunt force trauma.

Officers claimed that paramedics couldn’t resuscitate Robinson because a bag of drugs blocked his airway. But in their own report, paramedics explained they were “unable to intubate due to trauma and blood in [his] airway.” Their only mention of the drugs was that the police told them Robinson had swallowed a bag of drugs.

Meanwhile, sheriff’s investigators relied largely on a police witness who was not part of the team that initially raided the house. The officers they interviewed who were in the house claimed they were looking elsewhere during the encounter or noticed Robinson struggling with Detective Drew White after they breached the bedroom. None described a bloody encounter between multiple officers in SWAT gear and Robinson, who was about 6 feet and 175 pounds.

White wrote in his own report that he threw an elbow to Robinson’s face as he tried to rush past the officers, knocking him backwards into the bedroom, where he flailed violently and resisted White’s attempts to handcuff him.

White, who was carrying an assault rifle during the raid, told the sheriff’s investigators a different version of that story: He said Robinson made an "aggressive move” after they breached the bedroom, so he struck him in the shoulder with the butt of his rifle.

“After Dontrunner and Alaysha were detained Dontrunner began to complain that he could not breathe,” wrote Alaina Mancuso, the lead Baton Rouge narcotics detective on the case, noting that they tried to intubate him but could not because his airways were blocked. Mancuso said Alaysha told her that Robinson had swallowed drugs when he saw the police coming.

Paramedics arrived at 4:52 and found Robinson lying on the living room floor with “copious amounts of blood” in his airway. He went into cardiac arrest during the ambulance ride to the hospital.

The emergency room noted major blunt force trauma. The Baton Rouge police officers gave doctors a third explanation for his injuries: the bedroom door had hit him in the head. The hospital report also did not mention a bag of drugs outside of what the officers told them.

Robinson was declared dead at 5:32 pm.

The 36-page sheriff’s investigation issued no findings or conclusions and leaves much unanswered. It does not address the conflicting accounts that Baton Rouge officers gave doctors, deputies and their own lead detective about Robinson’s injuries. It does not question the information that led narcotics detectives to send a SWAT team into Robinson’s house on a no-knock warrant. They did not interview the other witnesses who were standing along the fence. It does not find fault or exonerate the Baton Rouge Police Department for Robinson’s death.

Sheriff’s detectives relied largely on the testimony of Mancuso, who was not inside the house during the initial raid and seemed to relay what White and others told her. Mancuso wrote in her own report that Robinson had “encountered medical problems while detectives were on scene.” She concluded that Robinson “died as a result of his medical difficulties.”

The sheriff seized a video surveillance system from Robinson’s house. As recently as August, the department claimed there were no videos stored on the hard drive. But Robinson’s family and the NAACP recently gave the hard drive to a computer programmer, who just this week recovered video files that could reveal additional new evidence.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Chief Paul said the police officers’ bill of rights prevent him from re-investigating a case that internal affairs already closed. He declined to talk more about Flag Street because of the pending litigation.

The chief pathologist in the coroner’s office ruled Robinson’s official cause of death was asphyxiation. Robinson had choked on a bag of drugs, according to the pathologist, which he had apparently tried to conceal in his mouth or swallow when police arrived. The pathologist’s report details each blunt force contusion and laceration to Robinson’s body: injuries to the head, neck, shoulders, chest, left arm and left leg. Thirty-two in total.

The pathologist did not note whether Robinson’s injuries contributed to his death.

Casa and Alaysha asked for the autopsy photos but said the coroner’s office told them the pictures were sent to the sheriff’s department. Because they never saw his body, they didn’t know the extent of his injuries.

Officials released them to Alaysha only after I emailed the coroner’s office. Once they were made public in June, the pictures — which show Robinson’s mangled face, his bloody mouth open and slack, the apple slice gouge above his left eye — stirred another round of local press coverage and outrage toward the Baton Rouge Police Department.

“I didn’t know my son was beat that bad,” Casa said.

She became fixated on the pictures, which, to her, confirmed she’d been lied to about how her son died. She locked herself in a room for an entire day, sobbing as she typed messages on her phone. “You don’t know the heartache they have caused me,” she texted. “I will not give up.”

Two mothers come to D.C., leave with potato chips

Since resigning from the Baton Rouge Police Department, Jeremiah has struggled to find full-time work. Collins found him a temporary gig in a vaccine education program, and he worked part time on hurricane relief efforts. Landscaping has been some of his most steady income. His mother pays him $40 to cut the grass even though she could just do it herself.

In July, the heat index was well above 100 almost every day with punishing humidity. Jeremiah would sweat through his shirt within minutes outside on a landscaping job. He was driving home one weekend in his truck when his legs started to cramp and seize. Then his arms went numb. He couldn’t grip the wheel or move most of his body. He managed to pull over to the highway shoulder, where he slumped in the seat and vomited onto the asphalt.

Heat stroke and extreme dehydration, the paramedics told him. You need to go to the hospital.

Jeremiah refused. He told them he doesn’t have health insurance anymore and the ambulance ride alone could bankrupt him.

Jeremiah and his fiancée can’t afford to repair their home, which has no floors and sparse furniture since a flood brought 10 feet of river water inside in 2016. They don’t have an oven, just a hot plate. Over the summer, the utility company shut off the water because they fell behind on the bills. They received a foreclosure notice in the mail. Jeremiah had to borrow money from family and friends.

”I’m about to lose every f---ing thing,” he said.

Jeremiah has considered filing a whistleblower lawsuit against the Baton Rouge Police Department. The system is set up to make it tough for him to succeed. Louisiana law puts the onus on whistleblowers to prove the misconduct they reported qualifies as a violation of state law — “not just a good faith belief that a law was broken,” as one appeals judge put it in a recent case. They must try reporting it internally. Finally, whistleblowers need to prove they lost their job or faced repercussions because they blew the whistle.

“Louisiana has taken a restrictive view of what a whistleblower has to do in order to qualify for protection,” said Andrew Burnside, an attorney who represents employers in Louisiana against whistleblower claims.

Or, as Gerald Melancon, a former officer in Amite who lost his own lawsuit in 2018, put it: “The bottom line is if you can't protect your officers when they blow the whistle, then what good is a whistleblower law.”

***

Casa and Mona Hardin — the five-foot-nothing mother of Ronald Greene, who died in Louisiana State Police custody — have become close friends. They lean on one another to help make sense of their new grim celebrity as Louisiana moms whose sons died in police custody. They frequently talk on the phone with Jeremiah to trade advice on how to navigate what they hear from lawyers, activists, reporters and politicians.

“Everyone gets a piece of you,” Mona says.

In early November, the two moms traveled to Washington, D.C. on their own dime to meet with U.S. Reps. Troy Carter, La., Al Green, Tex. and Sheila Jackson Lee, Tex., all Democrats in the Congressional Black Caucus. Casa had a locket with Robinson’s picture around her neck. Mona wore a leather jacket and a green shirt to commemorate what her son Ronald wore the night he died.

It was Casa’s first time in Washington. On her way downtown, she looked out the window trying to identify monuments and buildings. She clutched in her hand a laminated piece of paper with the talking points she had prepared with the help of Collins at the NAACP. She also brought with her photos from the autopsy she wanted to show the politicians.

She locked elbows with Mona while they walked the marble halls of the U.S. Capitol Building. As three young staffers brought us up the elevator to Carter’s office, Casa breathed heavily and looked at her feet. Mona, who was stoic, rubbed her friend’s shoulder.

They asked me to join them to help document what happened in the meeting. But just outside Carter’s office, his chief of staff, James Bernhard, put his hand on my chest and said journalists were not allowed inside because that would be against the closed-door policy for meetings like this.

They were in the room for about an hour. Afterwards, Mona, Casa and Collins, who was in attendance as well, said the politicians spoke at length about how important and brave the two moms were. They discussed national legislation, including the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which had been hailed as landmark legislation. The bill passed the House and then foundered in the Senate. It now goes largely unmentioned by lawmakers in public.

Mona and Casa said they introduced themselves but did not have time to read from their prepared statements or show pictures. Carter closed the conversation by recommending other politicians the women should talk to, including state lawmakers and the Republicans who they blamed for killing the George Floyd reforms.

On their way out of the meeting, Mona and Casa were given little bottles of water and a bag of chips.

Carter's spokesperson told me the families had as much time as they wanted to speak. Carter, who had previously called for a federal investigation into the Louisiana State Police, said in a statement that the meeting was just a starting point. “Meeting with and listening to these family members was powerful, humbling, and sobering all at the same time,” he said.

As they walked out of the Capitol Building, Mona asked Casa, who looked shaken, if she was doing alright. “Just getting myself together,” she replied. Casa’s attitude about how the day went oscillated between gratitude — “We did what we came here to do” — and frustration — “They shorted me.”

That night, over dinner and margaritas uptown, Casa and Mona discussed their roles in the theater of Washington politics. Casa slipped into fits of tears. “I paid to come up here for you to tell me to go talk to Joe Blow?” she asked rhetorically.

Mona tried to maintain her composure. She has learned to steel herself in public, in part because of a pending lawsuit against the State Police and because she’s become savvy in ways that she wishes weren’t necessary.

“I have to think of my son like a statistic so I can talk to Congress,” Mona said. She knows that any new federal law won’t change the fact that their sons are dead but reckons it might give those deaths some meaning and help their grandchildren one day.

“Why,” Mona asked before the night ended, “do we have to do a song and dance to keep our children from getting killed?”

The march goes on

It’s been one year since Jeremiah’s colleagues came to his house looking for stolen electronics. The criminal charges are still hanging over his head and he’s received no clarity about where the case stands.

Jeremiah said the unresolved charges are a convenient way to discredit him indefinitely, even though the misconduct he exposed has led to hundreds of expunged criminal charges, changes in policy and arrests within the department.

Jeremiah’s worried about explaining his whole story — why he turned on his colleagues, aired his bosses’ secrets and ended up in the news — to prospective employers. Would they understand?

“I did what I did because it was the right thing to do,” he said.

Once a reluctant whistleblower, Jeremiah is now immersed in the broad effort to hold the Baton Rouge Police Department accountable. He spends much of his time on the phone with lawyers — not to discuss his own case, but to help review old files on behalf of clients arrested by the now-disgraced narcotics division. He has been a guest speaker in college lectures about civil rights and police reform in the South.

This summer, he marched alongside Casa’s family in downtown Baton Rouge.

Jazz music played for a wedding reception while the sun set over the Mississippi River levee. Sharply dressed couples looked up from their cocktails and dinners to see about 100 people marching down the streets, chanting Justice for Dontrunner. Some of the onlookers asked one another if they knew who that was.

Casa led the crowd, followed closely by Robinson’s brothers and local NAACP officials who had helped organize the event. Their group stopped in several intersections, blocking traffic for about 10 minutes while they held hands in prayer.

Baton Rouge police squad cars parked along the protest route, lights flashing. One officer grinned as he appeared to be filming the marchers shouting the name of the officer accused of beating Robinson in the moments before his death: Lock up Drew White!

Jeremiah kept mostly to himself, walking on the edge of the group. Casa said that if it weren’t for him, she never would have known what happened to her son. “It would all still be the same,” she said. “He’s one of the family.”

Jeremiah recognized the police officers in uniform parked at the cross streets and they likely recognized him. But neither acknowledged the other as Jeremiah marched past.

He’s now taking calls from men like Brett Percle.

In June 2014, about a year after the Flag Street raid, Acree and others in the narcotics division raided a house on the Louisiana State University campus looking for marijuana. Percle, a student visiting his friend who lived in the house, later filed a lawsuit alleging that one officer stomped on his head and kicked out his front teeth. Acree strip searched him.

A jury in a civil trial ruled in 2016 against both officers. Two other cops on the raid — including at least one who was also inside the house on Flag Street — had testified that they didn’t see any excessive force.

Percle suspects one of the officers on the LSU raid stole hundreds in cash from the house and some of the marijuana. After he saw Jeremiah speaking publicly about misconduct in the department earlier this year, he texted him about the case to see what else he knew.

“I will call you shortly,” Jeremiah texted back. “We can talk."

USA TODAY reporters Daphne Duret and Gina Barton contributed to this story.

Contact Brett at brett.murphy@usatoday.com, @brettMmurphy, by Signal at 508-523-5195. Contact Gina at gbarton@gannett.com, @writerbarton. Daphne Duret is a 2021-22 Knight-Wallace Reporting Fellow at the University of Michigan. Contact Daphne at dduret@gannett.com, @dd_writes, by signal at 772-486-5562.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: The price cops pay for exposing misconduct in Louisiana