In Athens With Michael Shannon, the Night He (Sort of) Reunited R.E.M.

Michael Houtz / Getty Images

This story was featured in The Must Read, a newsletter in which our editors recommend one can’t-miss GQ story every weekday. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Radio Free Europe

Every R.E.M. fan has a version of this story. Mine is set in Riga, Latvia, in early 1991. I am 14. There are barricades in the city center: A few weeks earlier, Moscow tried to bring my newly independent country to heel by force. There is also, not unrelatedly, CNN International on TV. Bobbi Batista breathlessly reports on events unfolding blocks away, making me feel slightly famous by proximity. At night, the same channel for some reason rebroadcasts MTV’s Top Ten.

You guessed it. “Losing My Religion.” The song floored me so hard I still remember the ones abutting it (Mariah Carey and Rod Stewart). Top ten hits were not supposed to sound like this: a five-minute mandolin epic with no real chorus, delivered in an urgent baritone by a singer who moved like he was being attacked by a flock of invisible crows. It also didn’t hurt that Michael Stipe was the most beautiful man in the world, and Mike Mills looked like a nerd I could be friends with. Whichever way my sexuality would eventually tilt, I was set for life.

But life, as the song goes, is bigger. Fandom is supposed to fade with age, but it was the band that faded instead. In 2011, R.E.M. performed what a friend of mine refers to as “the hardest quit in the history of rock”: an amicable, no-drama dissolution that’s led to precisely zero solo records over the twelve and a half years that followed. (Yes, Stipe keeps threatening us with a good time, but his focus these days is clearly on the visual arts and being a hypebeast.) Let lesser men cling to the money and the fame. The boys from Athens, Georgia, went out the way they came up—with utter dignity.

One side effect of this move, however, has been a kind of planned obsolescence: all corner, no spotlight. What, exactly, is R.E.M.’s legacy? For a band that more or less invented the ethics of indie rock, fronted by a queer icon, where is their influence? Where are the new fans? (The band members’ excitement about being featured on The Bear last year felt more befitting a local outfit getting its first break.) How has their once-towering stature diminished to the point that Ariana Grande can call her cosmetics brand “R.E.M. Beauty” and no one bats a well-moisturized eyelash? And where does this leave the aging but still ardent original fan base—which is a convoluted way of saying “me”?

Pretty quiet, for one thing. What’s there to talk about, when the band themselves admit to having said everything there was to say? None of us, or them, is deluded enough to claim that R.E.M. quit at the peak of their songwriting powers. But also, let’s be honest: It leaves us feeling a little abandoned.

Look: Everyone knows why the Beatles are not playing Wembley this year. The answers are Mark Chapman and lung cancer. Likewise, everyone knows why the Smiths won’t reunite, because Morrissey. But Michael, Peter, Mike, and Bill are still with us, still friendly with each other, and not even that old. (Stipe, for instance, is younger than Nick Cave, Madonna, and Robert Smith.) Would it really kill them to—No. Bad fan. Don’t.

Left in this limbo, we can only talk amongst ourselves, which is surprisingly hard, because we’re a low-profile bunch. Being an R.E.M. fan was never an identity. You wouldn’t recognize one on the street. You only find this out as trivia: Adam Scott is one! So is Stephen Colbert! There’s an R.E.M.–themed bar in rural Belgium (I am not making this up)!

This partly explains why, upon reading that the actor Michael Shannon was performing Murmur—the band’s iconic 1983 debut—in Athens, I bought the ticket before even processing the MadLibs nature of what I had just read. If nothing else, I’d get to be in a room full of fellow fans. Which, I strongly suspected, was Shannon’s motivation as well.

Pilgrimage

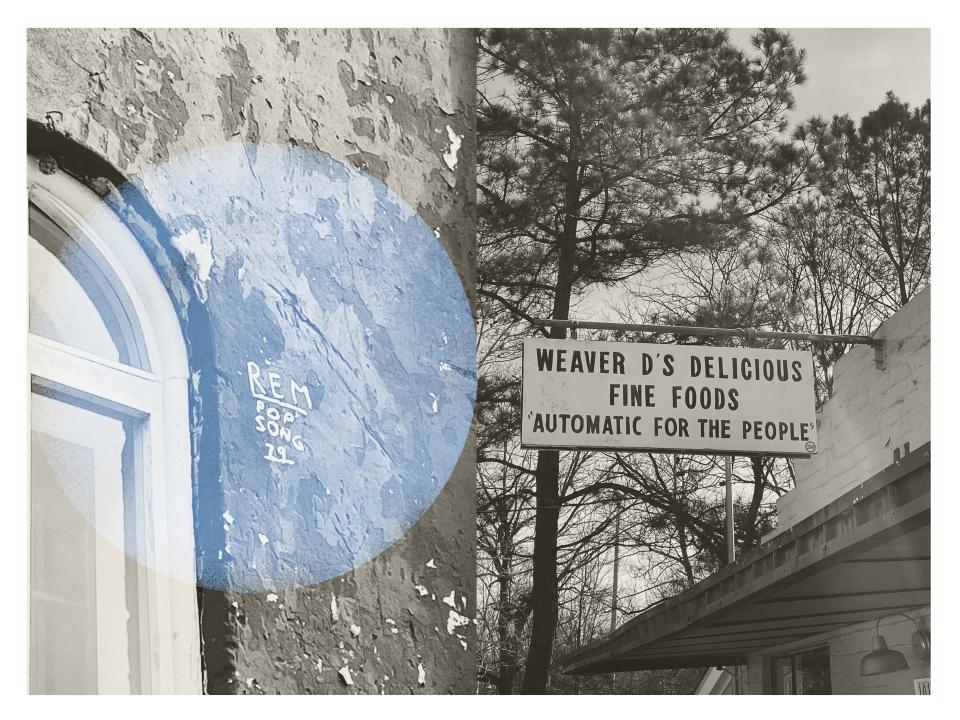

Shannon and I meet at Weaver D’s Delicious Fine Foods, the soul-food shack that used to be a regular haunt for the band. The diner’s sign, stenciled on a piece of board in an instantly recognizable font, reads Automatic For the People. In 1992, the year my family moved to the U.S., the R.E.M. album that borrowed this motto sold 18 million copies. As I am taking a photo of it, I see Shannon taking the exact same picture from the other side.

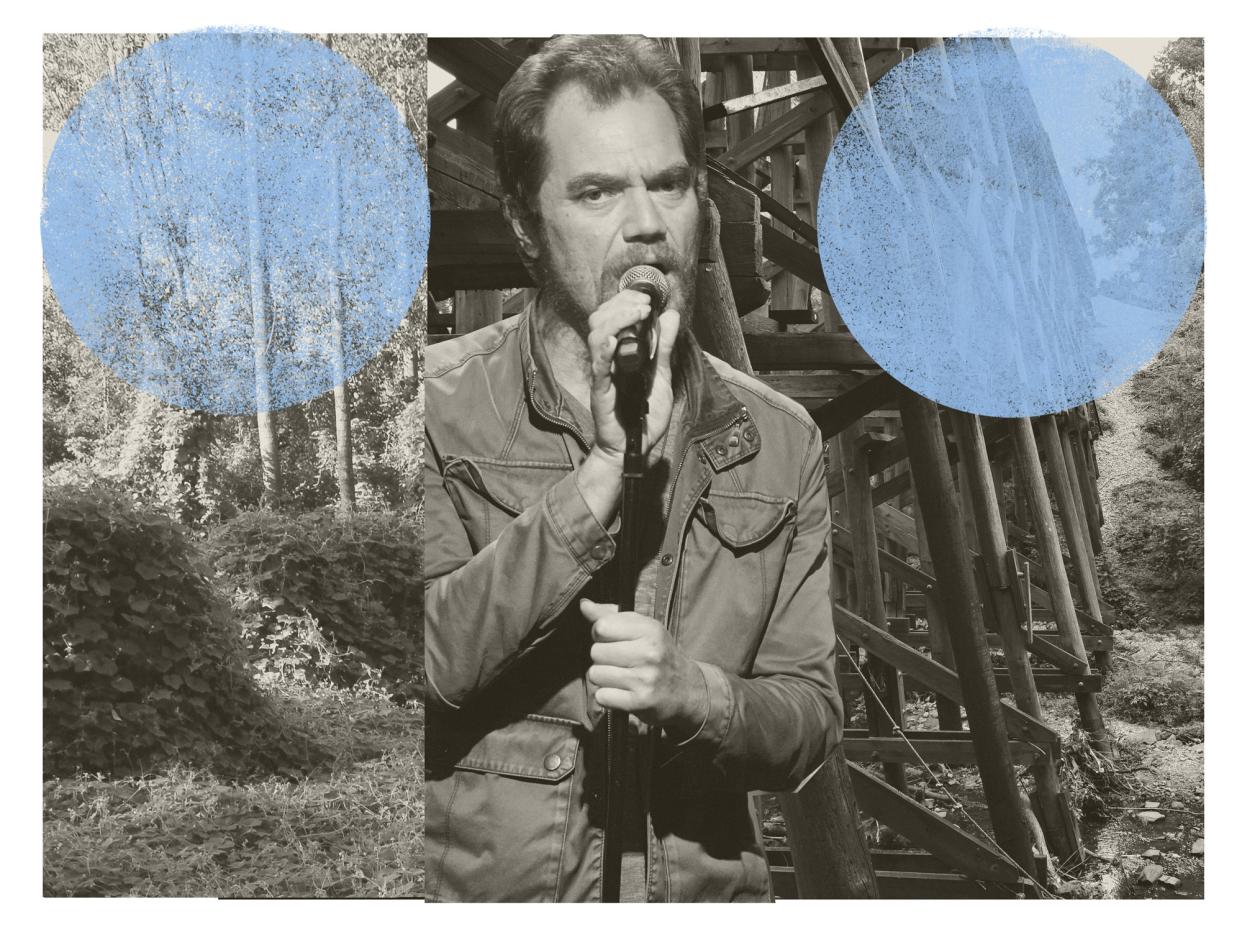

One of our finest actors, Shannon is an intensely introspective cat with a craggy, sculptural face. His specialty, in a filmography that reaches back farther than you think (he was in Groundhog Day), is ferocious men embodied ferociously. In 2023, he and guitarist Jason Narducy, a Midwestern alterna-rock legend, ran through Murmur in Chicago’s Metro to mark both the album and the venue turning forty. A frustrated former songwriter like, uh, some of us, Shannon does this kind of thing from time to time, always as a one-off; he’s done the Smiths’ The Queen Is Dead, Bowie’s Scary Monsters, and Lou Reed’s The Blue Mask. The Metro gig, however, was such a success he and Narducy hazarded an actual tour, Shannon’s first ever.

Not unlike Stipe in his current visual-artist era, Shannon is more than aware of the pitfalls of doing one thing while being famous for another. “I can’t think of a single actor who’s made a record and I’ve been like ‘Oh boy, I can’t wait to get that actor’s record, I bet it’s amazing,’” he tells me. “I don’t want to listen to actors make music! But yeah, it’s frustrating. Because I do like music. And I frankly am more passionate about music than I am about movies.”

There are still six dates left on the tour’s calendar, but there’s no question that this is the big one. This is Shannon’s first time in Athens, and he, too, seems cowed by the gravity of the situation. “I’m a nervous wreck all day. I can’t think about it. Tonight is too much to wrap my head around,” he says. “It’s one thing to go to San Francisco or Minneapolis or whatever, but to actually be here…” Singing Murmur on R.E.M.’s home turf, at the legendary 40 Watt Club, is an ultimate test for any fan. (Flying in from LA to hear what is essentially a cover band is, I submit, a close second.) Shannon is also battling a cold, and has a green scarf wrapped around his neck at all times, afraid his voice could go at any minute.

We order our food—a pork plate for him, fried chicken for me, a side of collard greens for both. The suave, bearded owner-operator, Dexter Weaver, is still there, working the register. It’s weird to meet the man whose name I somehow knew as a teen living thousands of miles away; I am admittedly more star-struck by him than by Shannon. A James Beard award certificate (2007, America’s Classics category) leans casually against the wall. A plea for $50,000 to “save this historic landmark” hangs opposite. We donate. “Where do you come from?” asks Weaver without recognizing Shannon. “New York? Been there once.” In 1994, when they were nominated for Automatic for the People, the band flew him to the Grammys.

Our next destination is marked on Google Maps as the R.E.M. First Show Church. All four band members used to bunk together in a deconsecrated Episcopal church; it’s also where, as a still-nameless band, they played their first set on April 5, 1980. (Yes, I am typing this from memory, glad you asked.) The city demolished the 1869 building itself, but a local suicide-prevention nonprofit, Nuci’s, kept and reconstructed the steeple.

We make our little pilgrimage, take our photos. It’s hard to place my exact feelings. Once more, it strikes me how we—all of us fans, not just Shannon and me—act as if we’re dealing with ancient history, as opposed to four guys who just don’t feel like recording new stuff. “It’s weird how available they are,” Shannon notes. “I mean, we thought when we announced this tour, they’d put out a cease-and-desist order. Instead, they embraced it.” In Chicago, Mike Mills, who knows Narducy, popped up to sing backup; who knows what will happen tonight. I try not to ask any questions so as not to jinx it. “I kinda met all four of them at this point,” Shannon continues, “and they’re all just sweet people.”

I am ready to let Shannon save his voice and energy for the show, but he seems happy to be distracted. The back cover of Murmur famously features a dilapidated train trestle, which, together with the kudzu patch on the front, rooted the record in a specifically Southern aesthetic; it is another ten-minute walk away, so we go to gawk at it next.

The city, recognizing it had a tourist attraction on its hands, has made the trestle a part of the Firefly Trail, a High Line–style urbanist flourish that runs through the local park. Unlike in the Murmur era, you can now walk atop it without risking death. “Is this it? Are we on it?” asks Shannon once we have climbed the stairs onto the trail. Yeah, we’re on it. What’s left of it. The original structure was demolished in 2021; the current one is a reproduction sandwiched between two steel arches. What’s better, oblivion or mummification?

I ask Shannon if, being an actor, he’s ever tempted to channel Stipe’s onstage manner. He rightfully bristles at the idea of impersonation, but the real-versus-replica talk leads us to the time he played Elvis Presley, in the oddball 2016 comedy Elvis & Nixon, despite looking nothing like the King. (“The casting feels so incongruous that it’s distracting—until, that is, you realize that Mr. Shannon is the only one that you’re paying attention to,” wrote The New York Times.)

“Initially, I thought it was a silly idea,” says Shannon. “I met with Jerry Schilling, who was one of Elvis’s best friends, and said, Jerry, I don’t look like Elvis or sound like Elvis, this is really strange. And Jerry said, ‘A lot of people in the world want to look and sound like my friend, but very few try to imagine what it was like to be my friend.’ And it gave me permission to do it. So I come at [Murmur] from that standpoint. What it must have been like. ’Cause these songs, they’re like a script. I’m doing this because I admire the music. I study the music as much as I can. I listen to that record every day, you know? I watch their old shows. There’s elements of trying to capture what Michael did. But no one will ever mistake me for him,” he says, with a tinge of sadness.

Our final station of the cross is a more upbeat affair: Wuxtry Records, the shop where Peter met Michael, is still itself and still going strong. We both get Mitski on vinyl for our respective teen daughters, and Shannon buys a Linqua Franqa T-shirt to wear at the show. I don’t say this to Shannon, but the choice to shout out the nonbinary Atlanta rapper and labor organizer seems like an extremely Stipean thing to do.

Shaking Through

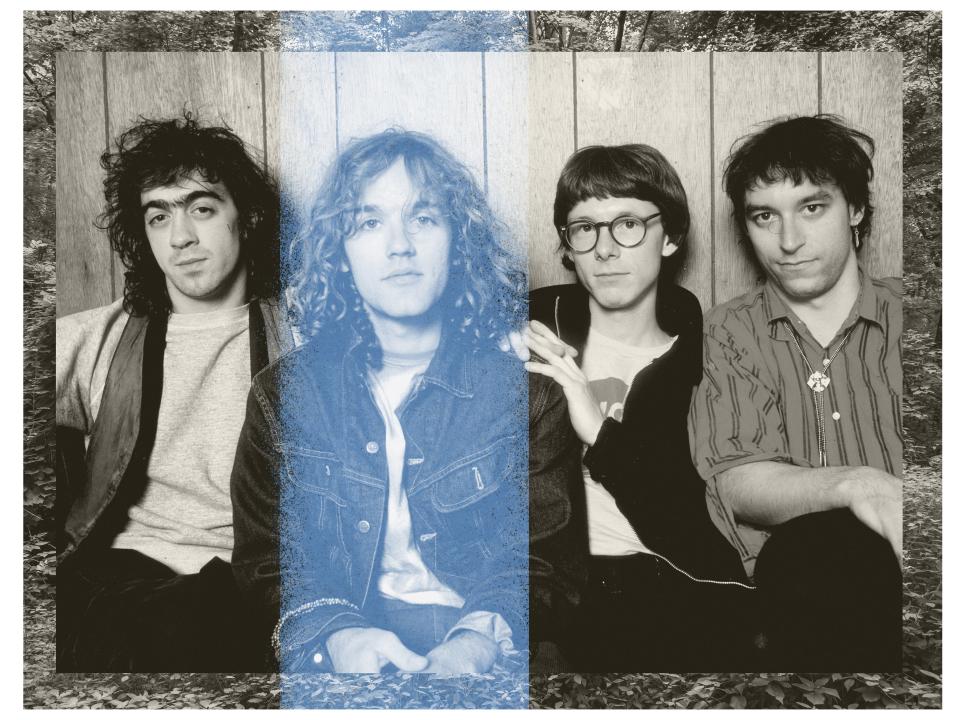

By 8 pm, the 40 Watt Club has filled up to capacity. About half of the crowd looks like a multiplied version of myself. The other half is older. I catch a glimpse of the guest list and nearly faint (Peter Buck+1, Bill Berry+1, Mike Mills+1, Michael Stipe+1). Also, for whatever reason, Ansel Elgort. Before the opener goes on, I run out to a nearby taco place, drink some tequila to calm my nerves, and, as I will find out later, lose a credit card. I get back inside less than a minute before Shannon bounds onto the stage in a black beanie and launches into “Radio Free Europe.”

The band behind him is a five-piece, a “fantasy league” (in Shannon’s definition) of Midwestern rockers put together by Narducy that includes drummer Jon Wurster from Superchunk. Unlike R.E.M.’s own early performances as a quartet, this setup allows the sound of the album to be recreated in a nearly ridiculous fidelity: the ambient intros, the slowed-down sound of crashing pool balls in the background of “We Walk,” the random snippet of what sounds like an unrelated studio jam at the end of “Shaking Through” are all preserved like holy artifacts.

The first moment of transcendence arrives with “Perfect Circle,” an abstract yet heartbreaking piano ballad that closes out Murmur’s side one. R.E.M. shared all songwriting credits equally but it is a known fact among the faithful that the main author of “Perfect Circle” is drummer Bill Berry, who left the band in 1997 after suffering a double aneurysm on the road. He’s been farming hay ever since, or whatever “farming hay” is a euphemism for, joining the band onstage only once, at their Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2007. “We have visitors,” Shannon deadpans as Berry and Peter Buck stroll onto the stage and casually begin to play live together for the first time in 17 years. The crowd goes as wild as this crowd can, then hushes up to listen. I film the first twenty seconds or so, then get angry at myself for putting a camera between my eyes and what they’re seeing, shove the phone into a pocket and spend the rest of the song blinking back tears.

With Murmur over and the night just beginning, the band plays all of Chronic Town, the quartet’s first EP, then another dozen early titles. Mills pops up on several tracks; so does Buck. Stipe, in a neon green hat, peeks out from the little pen left of the stage that functions as 40 Watt’s VIP area, clearly visible to the hometown crowd.

Cashing in on my privilege as Shannon’s guest, I transfer myself to the same pen and find a spot on an old couch. My memory of the next hour is instantly hazy, a swirl of bliss and the blues with the faintest shade of largely self-directed cringe. I don’t try to chat with any of the four. I just sit and watch them mingle contentedly with their friends and families, as a facsimile of their own youth beams at them from the stage.

The people who truly love R.E.M. know that they were the best band in the world but tend to have trouble articulating why. It wasn’t what they did but how they did it: Mills’s melodic bass, Berry’s near-monastic restraint behind the drum kit, Buck’s way with the arpeggio, Stipe’s oblique lyrics, the way all these choices meshed into one. This makes their songs hell to cover, especially, one must say, for cis men. One extra drop of testosterone and they become frat rock. (A good test case: Hootie and the freaking Blowfish, whose “Losing My Religion” is perfectly faithful yet somehow unlistenable.) Shannon’s voice is gruffer and less versatile than Stipe’s but never cheesier; it works, especially on country-tinged tracks like “(Don’t Go Back to) Rockville” and “Country Feedback” or raucous yellfests like “Just a Touch.” The latter is an especially clever choice: It is about an Elvis impersonator, which works on at least two levels here. Its lyrics, unusually direct by Stipean standards, were inspired by seeing the poster for the act—“Is It the King… Or Just a Touch?”—on the night of Presley’s death.

At times, I steal sidelong glances at Stipe to check his reaction to the just-a-touch version of R.E.M. onstage. It appears to be pleased but muted—until Shannon & co. play “Swan Swan H,” a delightfully goofy sea shanty off Lifes Rich Pageant. He begins to rock back and forth, then mouth the words; his hands fly up in the famous, apparently involuntary voguing motion I had spent my teens miming into the mirror. This creates an unexpected conundrum: If I am watching Michael Stipe lip-sync to a cover to an R.E.M. song, am I—in the same ship-of-Theseus way the trestle in the park isn’t, but still is, the original Murmur trestle—watching him sing R.E.M.?

The show ends with a rousing “These Days,” one of the band’s hardest, fastest, and most optimistic numbers. “Okay, we’re doing it,” yells Peter Buck, gesturing to the other three and giving everyone else in the pen a little heart attack. The “it” in question turns out to be going on stage together to thank Shannon and the audience. It’s as close to a reunion as the fans will get. It’s fine. Dayenu. For me, the glimpsed “Swan Swan H” moment would have to suffice.

The next morning, I check out of my hotel, stealing a magnetic key card designed to look like Stipe’s UGA student ID, and drive to Atlanta to catch my plane. I am strangely elated. Last night felt like a permission to move on, or not to. It is okay to get older, okay to stay a fan, okay to fall out of love and refuse to stoke the fire artificially. R.E.M.’s slow dissipation into the ether is just their authenticity in its final form; it should be ours, too. I see a massive growth of kudzu blanketing a roadside field, and stop the car to stare at it for a while. The weed doesn’t need a preservation committee or a fundraising campaign or our attention in order to thrive. It just grows over everything, choking out all other life. But there’s a grace in its inevitability, too.

Michael Idov is a screenwriter and novelist living in Los Angeles.

Originally Appeared on GQ