Ibis Colindres Was Told She'd See Her Son Again in 3 Days. It's Been 36.

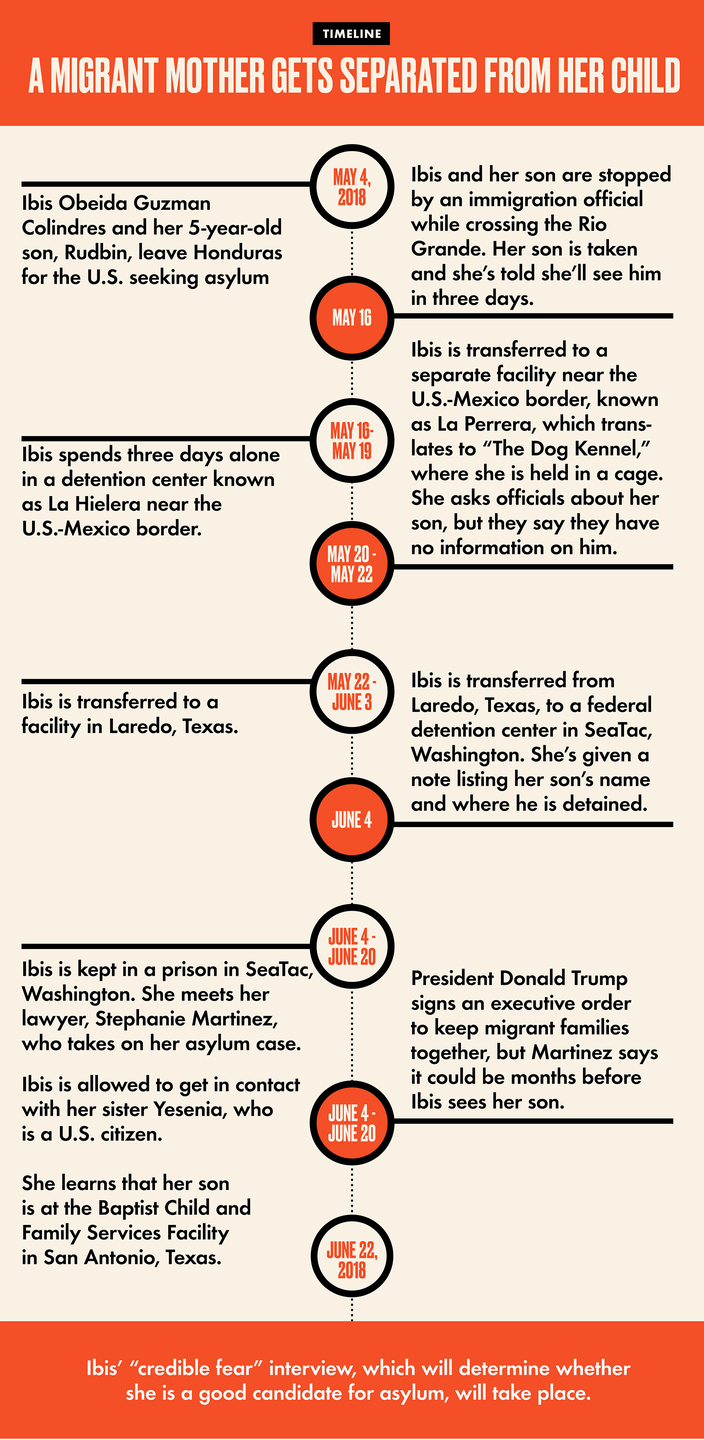

On May 4, Ibis Obeida Guzman Colindres left her home and her job as a daycare worker in Honduras with her 5-year-old son. Her homeland, which suffers rampant crime over political tensions, had become too dangerous, and a new life with her mother and half-sister in California seemed like the only way out. So, they started the long, perilous journey to seek asylum in the United States.

For 12 long days, the 25-year-old single mom and her son journeyed by foot through the murky waters of the Rio Grande. Days passed without them seeing another person. But on May 16, they finally crossed paths with someone: a U.S. border patrol agent.

The agent took them to a detention facility on the Texas side of the U.S.-Mexico border that immigrants have nicknamed La Hielera, which translates to The Ice Box, because of its freezing temperatures for those coming in from the desert.

After agents questioned Ibis for a few hours, Rubdin was taken from her. As he tried to hold on to her and screamed “No, Mami, no!” tears streamed down Ibis’ face as she desperately pleaded with the agents. She asked where they were taking him and when they’d bring him back.

She was told: “You’ll see him in three days.” Ibis has not seen or spoken to Rudbin since.

It’s been 36 days.

Rubdin is one of at least 2,000 children separated from their parents at the U.S. border between April 19 and May 31 as a result of President Donald Trump’s administration’s “zero tolerance” policy which charged migrants-including asylum seekers like Ibis-with a federal misdemeanor.

Though Trump signed an executive order this week ending the policy, Ibis’s lawyer, Stephanie Martinez of The Northwest Immigrant Rights Project (NWIRP), says it could still be months before Ibis and her son are reunited.

“NWIRP does not view the executive order issued yesterday as a positive development because it swaps one form of trauma-family separation-for another-indefinite family detention,” says Martinez, who has requested ICE release Ibis on parole so she can be with her son.

“ICE has not provided any information on how they intend to reunify families that have already been separated, and we will reject any reunification that would mean that parents and children will continue to be detained."

Martinez visited Ibis earlier this week in a detention facility in SeaTac, Washington. Martinez passed along my questions to Ibis and relayed her quotes.

On May 16, after being separated from her son, Ibis spent three days in La Hielera. It was the first night she’d ever spent apart from her son. Because she worked at a daycare back home, the two were never apart.

She says she was fed very little and slept with 20 other people on the floor. And she relived the horror of her son being taken from her over and over as she watched each new parent arrive. Worst of all, she had no idea where her son was. She asked officials if her son had been taken to stay with her sister, a U.S. citizen, and her mother, a lawful permanent resident, but no one would answer.

On May 20, Ibis was transferred to La Perrera, another facility near the border. This one earned its nickname, which translates to The Dog Kennel, because of the cages in which inmates are kept. While there, she pleaded again with officials to give her information about her son.

“When I would ask about Rudbin, they would say, ‘We don’t have any information to give you,’” Ibis says. “I was horrified.”

Two days later, Ibis was taken to a third facility in Laredo, Texas. She thought constantly about her son-even if he was safe in a shelter, she was worried he was refusing the meals.

“I was terrified,” Ibis says. “I was afraid that he wasn’t eating without me there. He’s only 5. I also feared that he was scared of being alone.”

On June 4, Ibis was transferred across the country to the SeaTac Federal Detention Center in Washington State. She didn’t know if Rubdin was still in Texas or if he’d been taken to a different state, too.

Upon arriving, an immigration official approached Ibis and silently handed her a piece of paper. It had her son’s full name and the words “The Baptist Child and Family Services Facility in San Antonio, Texas.” BCFS describes itself online as a “global network of non-profits.” (When I called to confirm they’re taking in children separated from their parents, administrative assistants said over the phone they had no information. Emails weren’t returned by time of publication.)

Finally, Ibis knew where her son was-and he was more than 2,000 miles away.

At SeaTac, Ibis was also able to contact her half-sister Yesenia Castillo-Colindres, who lives in Victorville, California. Yesenia, 22, was born in California, after her and Ibis’ mother, Maria Castillo, illegally crossed the border in the 1990s.

Yesenia and her family didn’t know Ibis intended to leave Honduras, following in her mother’s footsteps, until Ibis and Rudbin were already on their way.

“Ibis called us from a cell phone [while crossing the border],” Yesenia says in a phone interview. At this point, it had been just days since Trump’s zero-tolerance policy had been enforced. Yesenia and her family say they did not yet know the consequences Ibis could face once she reached the border, and so they were more concerned with what Ibis and her son could come across on their journey alone through Mexico.

When Yesenia found out her sister and nephew were on their way, she began preparing a spare room in her home for their arrival. But on May 16, Ibis called to say she’d been detained. Ibis’ mother, who had taken a similar risk when she crossed the border more than 20 years ago, immediately took the phone to talk to her daughter. She tried to calm Ibis down as Ibis screamed over the phone in Spanish, “They’re taking my son!”

Before hanging up the phone, Yesnia heard Ibis give officials her home address in California. Soon after, Yesenia received a package in the mail that allowed her to apply for Rudbin’s sponsorship. She submitted the paperwork and was told it could take up to 10 days, but she has not yet been approved. “They keep pushing it back, and back, and then months become years,” Yesenia tells me, becoming emotional over the phone.

In the meantime, Ibis has been told she can speak to her son, but Yesenia says Ibis’ calls never go through.

"It's very difficult to coordinate between facilities,” Martinez explains. “Because the policy is new, these places that house immigrants don’t have procedures in place. Normally it’s not such a necessary thing to have routine phone calls between two detention facilities."

While Ibis is shuffled from one detention center to another, Rudbin and his case worker have been in contact with Yesenia, who says she was first able to speak to her nephew on May 18. Yesenia gives her sister updates on Rudbin every time they speak, which is a few times a week.

According to Yesenia, the case worker told her the 5-year-old was having a hard time eating without his mother for the first few days, and has also been accused of “acting out” in his physical education class. Yesenia says, “When they were running, he would just be sitting down.”

Yesenia says the case worker promised check-in calls from Rubdin every two weeks, but they haven’t been consistent. She'd call herself, but she doesn't have the number. Whenever the shelter calls to let her speak to Rubdin, the call comes in as an “unknown” number on her Caller ID.

When Yesnia and Rubdin do speak, the phone calls are highly monitored. Yesenia says she can always hear an adult whispering in the background of the calls.

“I just know when he talks on the phone there is someone telling him how to answer the questions,” she says. “There’s always someone there, so I guess even if he wanted to say something else he couldn’t.”

When Rudbin asks for his mom, Yesenia says, “We let him know, ‘Your mom says she loves you.’ I guess he just assumes that she’s here. We just say, ‘No, she’s still not here.’”

Ibis’s lawyer Martinez says it’ll be months before she’ll see her son. And it could be even longer until they find out whether they can start their new life together in the U.S.

The asylum process can take from four to six months. Ibis’ first hearing has not yet been scheduled. On Thursday, Ibis was moved yet again to the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, and Martinez has not been given an explanation for the move. Ibis' first interview, to determine whether she had “credible fear” to leave Honduras, is scheduled to take place this Friday.

When Ibis is asked what she’ll say when she finally sees her son, she started crying and said, “That I love him.”

('You Might Also Like',)