A moment that changed me: my dad helped me with everything – then suddenly he was gone

On a cloudy Monday morning in March 2003, my father came into my room to check on me. I felt him pull the blankets up around my neck – something he used to do when I was a child. He lingered for a moment, then quietly left the room. That was the last glimpse I ever had of him.

On that day he took his own life. He had been suffering from sinus cancer for the last four months. A marble-sized tumour was found wedged inside his nasal passage after he began having unexplained nosebleeds in late 2002. He had surgery to remove the tumour and even though it was a success, I could see the huge physical, mental and emotional toll treatment was taking on him.

His death was a huge shock. We desperately searched for answers. The only explanation the doctors could give us was that my dad’s frontal lobe was significantly damaged from the radiation treatment he was receiving, which could have led to changes in his personality and behaviour.

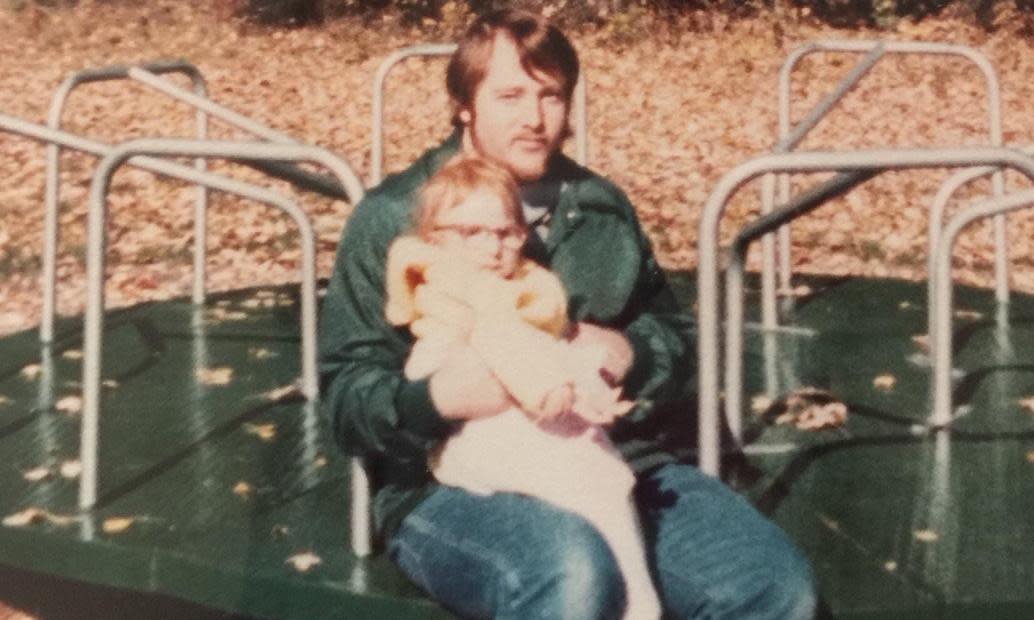

I was devastated. For more than two decades, my father had sat by my bedside through every single one of my hospital stays. I was born with Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, a rare genetic bone and muscular disorder. I had my first surgery, to turn my legs and feet around, when I was just ten weeks old, and had various procedures throughout the years.

My disability shaped my childhood, but my father’s suicide and its aftermath is what has informed so much of my identity as an adult. I was 21 when he died, that in-between age where you’re too old to be a kid, but too young to feel like an adult. In my grief, I found myself straddling the line the same way I did during my days in hospital as a kid. While in the hospital, I had these very adult, sometimes life-or-death experiences, yet I wasn’t an adult. I was a child. Only, I didn’t feel like a carefree kid, either. Child or adult, I didn’t feel as if I fit in either category.

When my father died, I walked that same tightrope. This time, I may have been an adult but I felt like a little girl. A little girl who had just lost her father and felt confused and scared.

I’m forever trying to find the right words to accurately describe what it feels like to lose a parent when you’re disabled. It’s a unique kind of grief because the relationship between a parent and their disabled child is a special one – during childhood, of course, but well into adulthood too, which is something that non-disabled people might not fully understand.

I relied on my dad in ways that my non-disabled peers didn’t on theirs. He helped me with everything, from showering and getting dressed in the morning, to cooking dinner in the evening. I’ve often said that he was “my legs”, and he helped me experience the world around me when it often felt inaccessible. When he died, this only added a more complicated piece to my grief puzzle. I wondered how I would ever do life without him.

I knew deep down that this went well beyond literal, tangible assistance such as food prep; to be disabled means to feel a certain level of vulnerability because so much is out of your control. I have felt vulnerable for most of my life and my father was the one who always made me feel safe and protected.

His suicide ripped away my sense of safety and replaced it with a fear of abandonment that I’d never experienced before. Will I lose everyone I love? Will everyone leave me? Will I end up alone? These were the sorts of questions that circled around in my head.

My fear of losing those I love plagued me and I became hypervigilant about my mum and sister, worrying about them constantly.

More than two decades after my dad’s death, I started seeing an amazing therapist. I initially went to talk through my grief, but opening up about losing him led to me opening up about my disability, too. I began processing what it meant to be disabled: how it had affected my life, how I never really felt like other people my age. And I gave voice to my worries about navigating life as a disabled adult – a fear I had been wrestling with since the day my dad died.

When you are disabled the bond you have with your parents can be heightened, but thankfully, as I’ve learned, that bond can also never be broken. Because even in death, my dad continues to shape my life and push me onward. I know that whatever happens he’ll always be with me.

• Beautiful People: My Thirteen Truths About Disability by Melissa Blake is published by Hachette Go (£25). To support the Guardian and the Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Blake can be found on Instagram at @melissablake81

• In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org