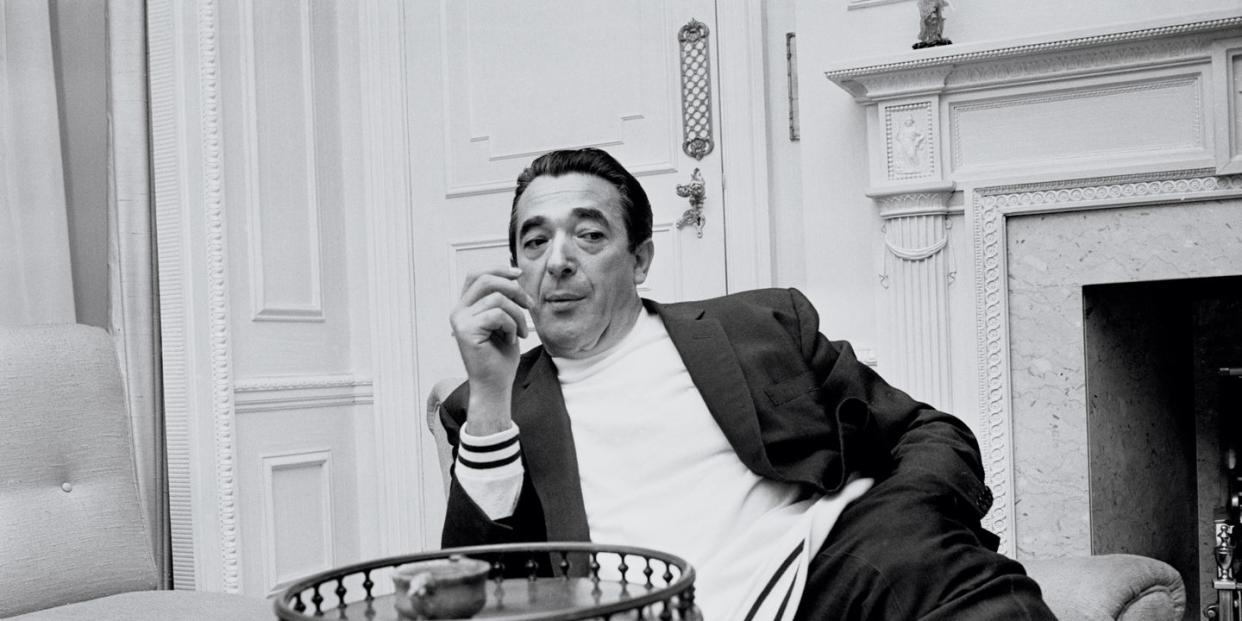

The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell

Can scandal be hereditary? Ghislaine Maxwell’s involvement with Jeffrey Epstein made her a household name, but her ongoing legal woes didn’t mark the first time her family had endured the glare of the spotlight.

When Ghislaine’s father Robert Maxwell died in 1991, the official cause of death was a heart attack—but not everyone was convinced. Rumors swirled that the larger-than-life newspaper baron, whose body had been found near the Canary Islands (he was presumed to have fallen off his yacht), had committed suicide in the face of financial ruin or been assassinated by some shadowy intelligence agency. And was it really any wonder?

Throughout his life, Maxwell worked tirelessly to obscure the truth about himself. He changed his name, denied his religion, and played shell games with vast fortunes, all in an effort to storm first the British aristocracy and later the international cabal of billionaires, businessmen, and power brokers. The plan worked. In his lifetime Maxwell became a global publishing tycoon—running such newspapers as London’s Daily Mirror and New York’s Daily News—a member of Parliament, and a bête noire for the likes of Rupert Murdoch and Margaret Thatcher. There were also rumors that he was a spy for Israel, or Britain, or both.

In the new biography Fall: The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell, Britain’s Most Notorious Media Baron, author John Preston follows the story of Maxwell’s life, from a destitute childhood in Czechoslovakia to the heights of fame and fortune. Preston deftly depicts how the trappings of money and power can be used to obscure a lifetime of secrets and lies. In this excerpt Maxwell’s uncanny ability to deflect attention with abundance is on full display—and serves as a chilling reminder that the apple never falls far from the tree.

The dinner dances hosted by Robert and Betty Maxwell at Headington Hill Hall were considered, even by hardened partygoers, to be in a class of their own. The house itself was an ideal venue for a party. It had been built in the early 19th century by a culture-loving family of brewers, the Morrells. They too had been keen party-givers. In 1878, Oscar Wilde was among the 300 guests at one of their fancy dress balls. For reasons that are not entirely clear, he chose to come dressed as Prince Rupert of the Rhine.

Ever since the Maxwells moved into Headington Hill Hall, they continued the tradition of throwing grand parties. But, as guests soon discovered, Maxwell had his own way of doing things. The writer and future Conservative MP Gyles Brandreth was a guest at one of their parties in the 1970s. At first nothing struck him as out of the ordinary. “It was only when I went up to Maxwell that I realized he had this apparatus on. There was an old-fashioned microphone attached to the lapel of his jacket with a windshield on it. And on his belt was this large box, the size of a hardback book with a dial in the middle. This was somehow connected to speakers in each of the rooms.”

Maxwell, Brandreth realized, was wearing his own personal PA system, enabling him to address people no matter how far away they were. “He’d turn the dial down when he was talking to you. Then, as soon as he saw someone he wanted to talk to on the other side of the room, he’d turn it up again, and this disembodied voice would come booming out of the speakers.”

For all the splendor of his parties, Maxwell himself remained an oddly elusive figure. “It was as if there was a kind of invisible moat around him,” Brandreth recalls. “He was definitely a presence, but whenever he came into a room, instead of the room being more crowded, it always seemed slightly emptier than before.”

As Maxwell’s fortune grew, the larger and grander the parties became. Cabinet ministers would rub shoulders with captains of industry, leading scientists with newspaper editors. But the joint party to celebrate Maxwell’s 65th birthday and the 40th anniversary of his company, Pergamon Press, in June 1988, was confidently predicted to outdo them all, in terms of both opulence and pomp.

No one, not even his many critics, could deny that Maxwell was on a roll: From Oxford to Osaka, his empire was booming. As he had boasted just a few weeks earlier, “The banks owe us money, we have so much on deposit.” At the same time, academic institutions were queueing up to bestow honors upon him; Maxwell had just been given a doctorate of law by Aberdeen University, as well as an honorary life membership in the University of London’s Institute of Philosophy.

So many guests had been invited—around 3,000—that it had been decided to hold the party over three consecutive nights. Friday night would be white tie and “decorations,” and Saturday night black tie, while the Sunday night party would be a more informal affair for members of staff. In between there was a lunch party on Saturday.

In the days leading up to the first party, vast marquees were erected around the house. Two floor-to-ceiling windows were removed to improve access to the main marquee. Legions of florists came down from London to create elaborate displays in the house, the marquees, and even the swimming pool—this involved them transporting the flowers out to the middle of the pool in little dinghies.

A stage had been built at one end of the main marquee and a dance floor laid so that guests could dance to the sound of the Joe Loss Orchestra; later on it would be a disco. At the end of the meal, the cast of the West End musical Me and My Girl would perform highlights from the show. To ensure that everyone enjoyed unimpeded views of the entertainment, the dining area had been constructed on two levels. A mobile darkroom had also been set up on the grounds. Guests who had their pictures taken during the evening by a team of six photographers would be able to collect them as they left.

To mark the 40th anniversary of Pergamon, a special book of tributes had been compiled. Pergamon had grown into the world’s largest scientific publisher, and the editors of Maxwell’s scientific journals—more than 300 in all—along with various Nobel laureates extolled his virtues in extravagant terms.

The editor of the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy noted, “Everything Bob Maxwell touches turns to gold,” while the director of one of his Japanese companies wrote, “Each time I have the pleasure of meeting him, I am reminded of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s words that a millionaire is no ordinary man.” Arthur Barrett, editor of Vacuum, recalled how his initial doubts about Maxwell had soon disappeared: “I have to confess that, quickly realizing his predatory and entrepreneurial ambitions, I none the less took a great liking to him.”

Among the congratulatory telegrams was one from the U.S. president, Ronald Reagan: “As the Happy Birthdays ring out, Nancy and I are delighted to join in the chorus of appreciation.” The prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, offered a somewhat solipsistic contribution of her own: “Robert Maxwell has never made any secret of the fact that officially he is politically opposed to me. But to tell the truth, I think he rather liked my approach to politics and Government—a sense of direction and decision. These are the very qualities that have taken him far.” As far as the Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, was concerned, “If Bob Maxwell didn’t exist, no one could invent him.’”

On the night of the first party, guests passed down a receiving line where they were greeted by Maxwell, Betty, and all seven of their children. Some of the guests arrived bearing birthday presents. The broadcaster David Frost turned up with a £500 bottle of wine. Unaware of how much it had cost, Maxwell’s chef later tipped it into a beef stew.

As guests sipped their drinks, the band of the Coldstream Guards marched back and forth across the lawn. Before dinner started, Robert and Betty made their formal entrance into the marquee to an announcement from the master of ceremonies—“Ladies and gentlemen, would you please welcome your host and hostess, Robert and Elisabeth Maxwell”—and a fanfare of herald trumpeters.

Everyone stood to applaud. Along with a row of medals pinned to his black tailcoat, Maxwell was wearing a large white enamel cross on a chain around his neck. This was the Order of the White Rose of Finland, a decoration normally given to foreign heads of state in recognition of “outstanding civilian or military conduct.” Betty Maxwell wore a dress made of gold-embroidered tulle over yellow taffeta silk.

At one of their earlier parties—in 1986—the speech had been given by a former prime minister, Harold Wilson. Suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer’s, Wilson had begun his speech brightly enough but then clearly forgot who he was supposed to be talking about. This time nothing had been left to chance. The main speech was given by Maxwell’s banker, Sir Michael Richardson, managing director of Rothschild’s bank and an economic adviser to Mrs. Thatcher.

“Betty and Bob, this must be the party of the decade,” Richardson declared to shouts of “Hear, hear!” and another round of applause. “All of us are delighted to be here, because we believe you have made a major contribution to all our lives.” But as she sat beaming away by Maxwell’s side, Betty found herself wondering if the party might not be too puffed up with self-importance, if something vital might not have been lost along the way. In particular, she had major doubts about the herald trumpeters. “I thought it was really over the top, but I managed to play my part… For all its success, for me, it had lost the intimate quality that our previous parties had had. It was just too vast.”

That evening the economist Peter Jay found himself sharing Betty Maxwell’s misgivings. “It was as if people came because they wanted to see Maxwell; it was a spectacle. And although they sucked up to him and enjoyed his hospitality, you could see them raising their eyebrows at the same time.”

After dinner was over and the cast of Me and My Girl had finished performing, guests were asked to go back outside. There they were treated to a fireworks display, the culmination of which was a huge flaming sign spelling out the words “Happy Birthday Bob!” across the Oxford skyline. But not all the guests stayed to watch. Some of them succumbed to curiosity and went snooping. Mike Molloy, by now the editor in chief of the Mirror, was particularly struck by the decor of Headington Hill Hall: “All the furniture looked as if it had been bought from the sale of a second-rate country house in the 1920s. And the paintings were absolutely terrible. I’ve never seen a worse collection.”

Having inspected the art, Molloy peered into Maxwell’s drawing room. “There were all these bookshelves with books on them. Except when I looked more closely, I saw that they weren’t real books: They were made out of cardboard. I couldn’t get over it. Here was this man who had made his fortune out of publishing, and yet there weren’t even real books on his shelves.” In fact, not all the books were false, only those concealing Maxwell’s stereo system.

While the dancing was going on, Maxwell asked another of the guests, Gerald Ronson, CEO of the property developers Heron International, if he would like to come into the house for a quiet drink. “He waved his fat finger at me and said, ‘Let’s go into the library, because I don’t want to talk to these people.’ ”

They were, Maxwell told him, “a bunch of arseholes” who would go anywhere if they were invited by someone important. It wasn’t just that, though: Maxwell had something he wanted to show him. “Bob said, ‘You always thought I was joking when I told you that I had won the Military Cross.’ He then opened a large photo album and proudly pointed to one of the photographs. Taken more than 40 years earlier, it showed Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery pinning the medal onto the uniform of a much younger, slimmer Maxwell.” Ronson laughed and held up his hands. “I said, ‘I take it all back, Bob. I’m sorry if I didn’t believe you, but you do tell so many stories…’ ”

From Fall: The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell, Britain’s Most Notorious Media Baron, by John Preston. © 2021 John Preston. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

You Might Also Like