How one Canadian YouTuber is shattering transgender misconceptions

As part of an ongoing series, Yahoo Canada is profiling personal experiences in open letters. This entry profiles Stef Sanjati a Canadian transgender video blogger known for her tutorials on makeup. Her YouTube channel has more than half a million subscribers, who are collectively known as the “Breadsquad.” Stef opens up to us about growing up with Waardenburg Syndrome, dealing with bullies and undergoing facial feminization surgery. For more from our open letter series, click here.

As told to Nisean Lorde.

I was diagnosed with Waardenburg Syndrome as a very young child. When I was born, I had a patch of white hair (which has since grown to cover almost a third of my head) that doctors were worried it was a tumour. My mother was never diagnosed, so they wouldn’t know to expect a child with symptoms related to the condition. They ran a lot of tests, worried that I may not make it, and after jumping between a few hospitals, doctors finally realized that the white patch was harmless. It was the result of a genetic condition called Waardenburg Syndrome, passed down from my mother. The doctors informed my family that I would also likely experience deafness in one or both ears, and that my blue eyes, facial structure, and any skin pigmentation differences were also a result of Waardenburg Syndrome.

My mother and I have nearly identical faces because of Waardenburg Syndrome, but so do many of my cousins. It is unmistakeable that we are related when we’re around each other — and when I look at old photographs, so many of my ancestors had my face, with their premature white hair. It has become a very large part of my identity, and now, after embracing it and loving it, I feel more connected to my family than ever before. I have cousins who are fully deaf, as well as relatives, like my mother, who have no hearing loss at all. I landed in the middle, with my left ear being deaf from birth.

ALSO SEE: Open letter: Olympian Dara Howell on why failure is OK

As a kid, I didn’t understand I was different physically until kids started to point it out. I remember a moment of realization — when I was eight or nine, an older kid in the schoolyard told me I looked like a fish. I recall honestly having no idea what he meant or how he could see that — and then I went home and looked in the mirror — and a several-year spiral of self-loathing, isolation, fear, and confusion began. I was picked on for my white hair, too, but I could brush that off fairly easily. Comments like “old person” weren’t that alienating or hard to digest as a kid, but “fish face,” “frog face,” “alien,” “Sid from Ice Age,” and quite literally “mutant freak” were a little bit more to handle. I was living a childhood from the X-Men without the benefit of powers to shut down the harassment. A few years later, when I was 10 or 11, I remember a kid picking on me for something else — my femininity.

As a trans person, I’ve always tried my best to be myself, even when I was a kid, and had no idea that trans people existed, let alone that I was trans. This kid was calling me gay as an insult, and normally I would just hang my head down and let people laugh. This time, I looked him in the eye and told him, “You know what? I know I’m not, and that’s all that matters. I don’t care what you think.” Word for word. I can’t believe little me had the strength or awareness to say that, but I did, and it was a turning point for my confidence.

I started to make new friends that weren’t as mean to me, and started accepting my features and understanding that they were beautiful, just different from all of the narrow, sharp, European features that surrounded me when I left home. My hope is that every kid that experiences this alienating, isolating bullying is able to stand up like that, and have the result I did: the bully shutting up, and their own spirits being lifted without any kind of retaliation.

ALSO SEE: Open Letter: ‘I survived breast cancer, now I’m helping other survivors feel beautiful again’

As a kid, I was always drawn to femininity. Not for any particular reason — nobody put a doll in my hands and said “you should play with this” — to the contrary, I remember my parents trying to give me more masculine toys like Hot Wheels or farm sets, but I would just take the animals and play and totally forget about the tractors. Eventually, they realized that Disney princess dolls were what made me happy and just let me be and let me play with what I wanted to.

It’s important that parents understand that forcing their child to be any certain way, or to like any certain thing is not only impossible, it’s incredibly harmful and inhumane. You are teaching your child that what they instinctively like is wrong, that they in turn are wrong and must fight their feelings and impulses. That is dangerous. That causes real problems.

Fortunately, my parents learned this very quickly. I remember my favourite was Esmerelda from the Hunchback of Notre Dame. I got her from a second hand store in my hometown — I also loved an Ariel mermaid doll I got from the mall a few towns over. I recall sitting in the food court with my mom and my brother, proudly displaying my new prize and eating my lunch, when a kid a few tables over started pointing and laughing. I didn’t understand. It never crossed my mind that he would laugh at something I loved so much, because who would? I thought maybe someone had dropped their food, and I kept on admiring my new doll. Eventually, as I got older, I started gaming more and playing with toys less. This came along with the social isolation of my femininity during puberty, as well as the alienation of having Waardenburg Syndrome and being told that made me a freak.

ALSO SEE: A rare birth defect brought these childhood sweethearts together

I retreated into my computer, following my brother’s footsteps into digital landscapes and fantasy worlds. Those worlds are home to me. I always say I grew up on the internet, not in my hometown, because I quite literally did. I learned how to interact with people by talking to a camera and to avatars online. I made friends there that cared about me more than my peers at school did as a young kid. It mattered. It saved me. I began experimenting with my gender as I got a little bit older — 12 or 13.

It was clear to me that I instinctively rejected male roles and traditionally male objects or clothing, but not out of any principle, just out of instinct. They didn’t feel right. I stopped participating in gym class in seventh grade because I was required to go into the boy’s changing room, and I instinctively felt wrong there. I knew I wasn’t supposed to be in there — like I was vulnerable and in dangerous territory. In high school, when people really started laying the harassment on thick with verbal slurs, vandalizing my property and my mother’s vehicle, chasing me in cars and stealing my things, I started to wear femininity like armour.

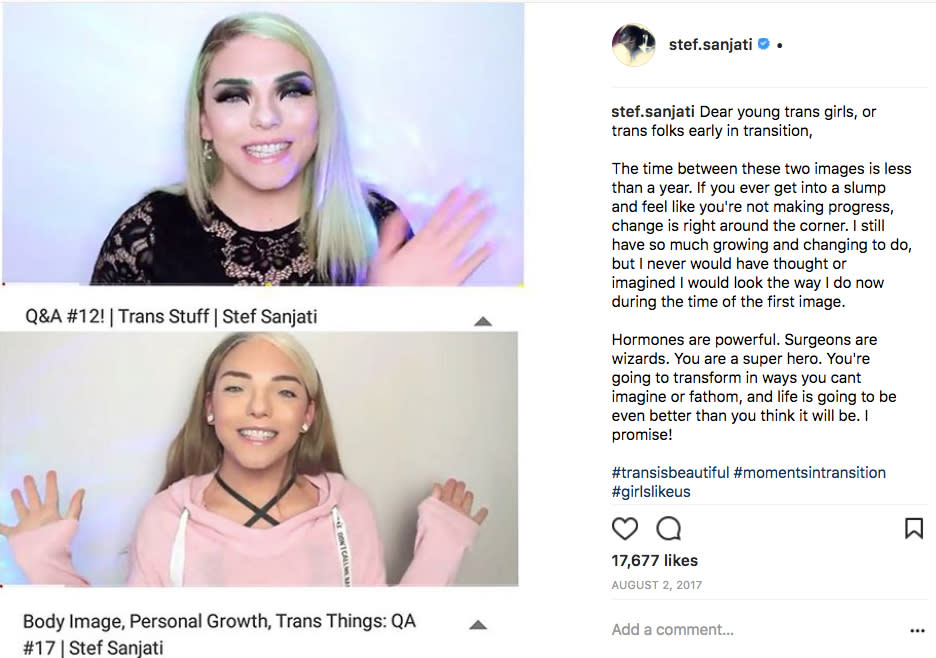

I painted my face in the most ridiculous ways, wore fashion that people from my home town would have never seen otherwise, and really made a point of saying “you said I didn’t belong? OK. I don’t. Here you go — this is what you told me.” They couldn’t sling something at me that I owned with my whole being. I continued with this pattern of fashion and expression to explore femininity until when I was 19 years old, well after college and living in Toronto, instead of my tiny hometown of Wallaceburg, when I realized I was transgender and began taking steps to medically transition in a way that would help me.

ALSO SEE: Selena Gomez claps back at bikini body shamers

When I was 13, I thought I was gay because I was attracted to men. Now I understand that’s not really what it was about — that I’m trans and attracted to people regardless of gender — but as someone young, trying to find an identity, and seeing what “GAY IDENTITY” was represented as, it caused a little problem called anorexia. I looked at my grand selection of role models and saw, 10 years ago, almost nobody. I fell into this trap of thinking I had to look like the gay teens that were popular online — skinny, tan, blonde. I tried my hardest to be that, and I suppose I succeeded, but at great cost. I was dangerously thin, on the brink of needing hospitalization. Everyone could see it but me, but my peers would still congratulate me.

It was addictive, the affirmation I would get from the same people that a year or two ago would call me “faggot” if I was within seven feet of them. It felt like a drug. That’s what I understand in hindsight, and what helped me recover when I was younger — that I was addicted to the attention and affirmation, not the look. I didn’t really even see myself or what I looked like. As an adult, I’ve had a lot of trouble with bulimia. There is a very specific look that a lot of trans women in LA go for — and while I was there for a business trip, I took some bad advice and got addicted to laxatives. I kept this up for half a year or more. I not only deprived my body of the nutrients it needed to function properly and the fuel my brain needed to give me happiness, but I also was flushing my body of my medications and threw my hormones way off balance, which resulted in more mental health issues.

It was a nightmare. I’ve been “sober,” (if you can call it that as it wasn’t a mind-altering substance) for about as long as I was in trouble for, and I can say that I feel so much better, but also look more like what I was striving for. It’s bizarre.

I don’t know what advice I could give to people struggling with eating disorders, because they’re all so different and everyone has different circumstances that land them in trouble, but I hope that anyone reading this can understand that these addictions never made me happy and never did what I wanted them to — they never made me look the way I was trying to look. Being sober now, and honestly not really striving to look any certain way, just keeping my hormones in check and treating myself with kindness — I now look the way I’ve wanted to look my entire life. I don’t know how to explain that, but it’s a feeling I hope everyone gets to encounter, especially if they’ve struggled with body image issues or an eating disorder.

ALSO SEE: Biracial twins, one black, one white, won’t let race define them

Online, I hear the same things I’ve heard my entire life in person. I read the same things today that I would hear on the schoolyard 15 years ago. Originally, I retreated to the internet because my physical circumstances were too stressful and hostile for me to grow and thrive in. I think there’s something about that digital barrier that allows both the hostile folks to feel free to harass and attack people, but also allows their victims to filter out the noise. I definitely, at this point, get a lot more positive engagement than negative, but it can still be hard to see through the attacks when they occur. When this happens, I remind myself that I’ve heard this all before, I’ve been there before and I’ve gotten through it. I’ve been fine. I’m going to be fine. That typically takes about five minutes of breathing and reminders, and then I’m back to remembering who I am.

Blocking features on social media are very helpful, as are blacklisting words that you don’t want to read. Most of the time, these comments don’t get to me, but I still try to curate my YouTube comments in a way that erases blatant hateful harassment, so that young kids trying to relate to someone, thinking they’re trans and wanting to immerse themselves in a community where they won’t feel alienated won’t have to read the same sh-t they hear in public day in and out. I want to give them some reprieve from that struggle.

When I was much younger, there were definitely times when I wished I didn’t have Waardenburg Syndrome. There was probably a solid year where I couldn’t look in the mirror without hyperventilating, because I hated what I saw so much. I think that had more to do with gender and puberty than Waardenburg Syndrome, but either way, as an adult now there is nothing that could ever be offered to me in the world, no amount of money or power that I would take in exchange for having my Waardenburg Syndrome features be erased. That wouldn’t be me.

I understand now that, quite frankly, I’m hot as f–k. I’ve had to deal with harassment, self-loathing, and bullsh-t for too long for me, now, to spend any time gratifying anyone who wants to tell me that my features make me ugly. I know I am desirable. I know I look good. I know I can be glamorous or soft or powerful with this face, and I love it. I love my face. I wouldn’t want a life without it.

ALSO SEE: 11-year-old gets cosmetic surgery after being bullied over her ears

When I underwent facial feminization surgery as a part of my transition, I specifically requested the surgeon not alter any Waardenburg specific features, like my eye shape or nose bridge or upper lip shape. This was a reconstructive surgery for me — to erase the damage done by testosterone during a puberty that sent my brain into shock for a good eight years. I was reversing that — not getting a new face. I chose my surgeon based on that principle, and landed on Dr. Spiegel in Boston, Massachusetts. I love the work he did. He altered everything so slightly, but all together, it made a huge difference and changed my life.

The way I see myself now is exactly as I want to — I wake up in the morning, look in the mirror, and think “gross, brush your teeth and brush your hair,” and not “I don’t want to live with this brow bone, I can’t go outside, I am worthless.” That alone — the first thing you say to yourself in the mirror every single day — that can change everything. I had five things done — a forehead reconstruction (mostly to reduce brow bone), a mandible (jaw and chin) contour, a trachea shave (Adam’s apple reduction), a lip lift and lip augmentation (raising the upper lip, creating a pout, filling the upper lip with the removed tissue).

Any one of these things alone would not have really changed the way I look, but with all five in unison, fully healed, it is exactly what I wanted and I wouldn’t change a thing about my results. I still look like me, just the me that I always knew I was, not the me that others perceived me as.

ALSO SEE: Mom’s heartwrenching photo shows the reality of post-baby life

I reveal almost everything about myself online. I think people want to learn, and people are curious, and of course there are trans folks who are looking for someone to relate to and someone to live their life and tell them it’s okay. I want to help all of those people.

I think, by being so open, by literally showing myself on the operating table mid-surgery or sharing my darkest moments, I can humanize an experience that is really normal, but is perceived as fringe or odd. I don’t recommend this life for everyone (concerning YouTube and vlogging with vulnerability, not concerning transitioning) — I have a lot of struggles because of this openness. I find it hard to trust, to make friends, to get outside because I work from home, to maintain balance in my life… the way I feel when I meet a viewer outweighs all of that, but it is still tricky. Be careful with what you share. Be yourself, be open, but protect yourself too.

For more, visit Stef on YouTube and Instagram.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA!

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram!