Open letter: 'There is NO such thing as anxiety or depression. Why? My father said so.'

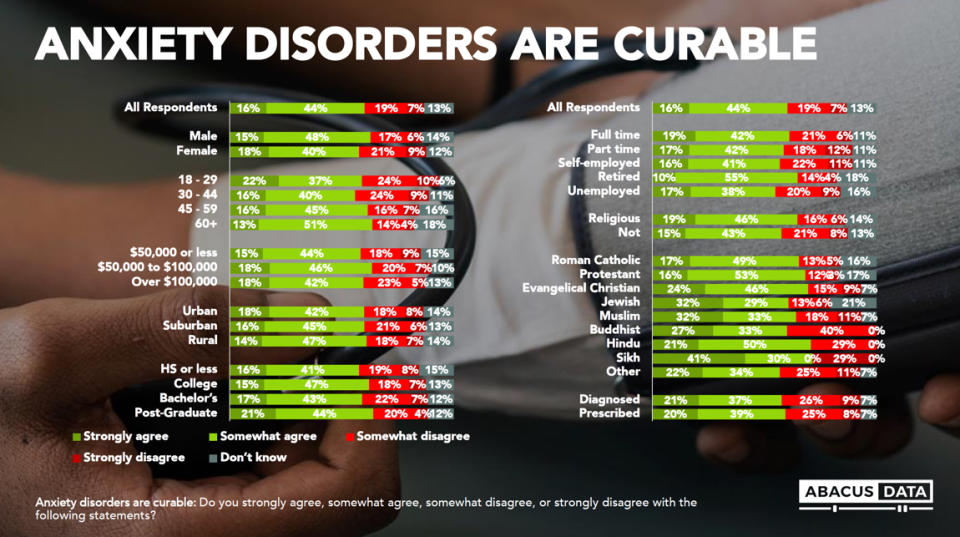

The struggle with anxiety has no name, age or race, but each of these factors plays a role in the way it is perceived in society. Abacus Canada conducted a study of 1,500 Canadians to weigh opinions on anxiety, and one of the standout findings revealed a pattern among those who practice particular religions. Individuals who identified as Muslim, Sikh, Jewish and Hindu faiths widely agreed – an average of 70 per cent of the time – that anxiety was curable. While the reasoning behind the beliefs remains relative, the following memories from Aisha Chughtai, a Muslim woman who has struggled with anxiety through the loss of her parents at a young age, may shed light on the stigma through the veil of culture and religion.

—————————————————————————————————————-

He sat across from me.

A vintage desk carved from wood separated Us from Him.

My father and mother sat on the chairs placed opposite of the man who sat behind the desk, while I stood beside them, holding onto my mothers’ hand.

He sat comfortably on his black office chair as he rested both his elbows on the arm rest, with his hands folded in his lap.

I remember feeling uneasy and unable to sit down, so I stood. I played with the tissue that I’d usually clench with my right hand while I focused on everything but the sound of their voices. I remember feeling the sinking of my stomach, as though I was on a never-ending bumpy rollercoaster ride – I’d been feeling that way for a while. Nothing Mom, Dad and I did had helped to ease this uncomfortable sensation. We tried everything from Gravol to Tums, traditional natural remedies passed onto my mother, but the sinking feeling in my belly, the chest pain and difficult breaths prevailed.

The man who sat behind the desk spoke to my father patiently with a slight Pakistani accent that made it difficult for me to understand what he was talking about. He smoothly transitioned from speaking some sentences in Urdu, to some in English, a common phenomenon adopted by many second-generation Canadians to provide us a cushion of vocabulary to substitute for the words in Urdu we aren’t exactly familiar with.

I stood beside my mother, my beautiful sick mother.

My beautiful mother who was often complimented for her youthful glow despite her age, sat beside my father, quietly. She had been looking gaunt lately. I could see the bright light from within her slowly fade into a very dim glow, only to be seen on the days she felt we, her children, needed to be comforted.

“I’m OK Aisha. I feel fine..don’t worry..I’ll be fine,” she would say convincingly.

I may have been young at the time, but It didn’t prevent me from noticing how much the ‘C’ word changed her. She once was a young woman who would sit on the chair in front of her dresser, indecisive about what colour to paint her lips. Now, she carefully selected a mask to cover up all the pain she felt inside. The pain that now framed her thin facial features, leaving her unrecognizable by others, but most importantly — herself.

I remember spending many nights in the emergency room with my siblings.

My father had nowhere to leave us, so along we went to every oncology appointment, every visit to the ER in the middle of the night and then – depending on if our hospital visit ended early or stretched into the morning – off to school we went the next day.

I would doze off discretely in class, trying to rest the palm of my hand on my temple while balancing my elbow on my desk. It carried the weight of my turmoil as I closed my eyes for just one minute. But, one minute would turn into a few, a few into a whole period, and soon enough, I would be awakened by the loud roar of the school bell.

ALSO SEE: “I don’t think people really realize what it’s like to live as an anxious person”

All the children around me would playfully run around the classroom, chattering amongst each other as they got ready for recess or lunch, but I would always find myself stuck to my chair, unable to move. I would sit and watch everyone around me, as I remained trapped inside of my head.

A hundred thoughts per minute raced through my head. I felt imprisoned by the constant worry that I would wake up one morning to a life completely changed, to a world short of one of the most important people in my life. My thoughts spun in circles as though I had my very own pet hamster living in my mind and he would not give his wheel a rest no matter how hard I tried to throw its rhythm off.

“Will Ummi be home when I get there?”

“I wonder if she is OK?”

“She never got out of bed this morning to send us off to school…what if something is wrong?”

“I didn’t ask how she was doing this morning?”

“Is she going to be OK?”

“What if I never see her again!”

“What’s going to happen to us?”

I was only 10.

I’d return from deep within myself, gasping for air as if I were drowning in this ocean of endless panic. I found myself wanting nothing more than to be physically as alone as I felt on the inside. I needed to be far away from the laughter of other children, far away from the reminder that deep down inside, I longed desperately to simply insert myself into their lives. Happier lives.

“They look happy! I want to be happy! Why can’t I feel happy?”

And as I could feel my anxiety level plunge , I’d finish catching the rest of my breaths alongside one of my teachers in a place I spent the majority of my school day: the guidance office.

In an effort to distract myself I’d dart my eyes around the office, but one day, I noticed a word stand out. There it was – “Allah” – in Arabic painted, framed beautifully and hung up on his wall. “God” I whispered to myself.

ALSO SEE: How does religion impact anxiety?

“I guess I could focus on that?” I thought to myself. It’s what my Muslim mother taught me to do when I was upset. She did it too.

As I finally returned from a very short but deep journey from within myself, I tuned into the conversation being had between my parents and the man that sat behind the desk.

My parents didn’t know what to do with me.

“She won’t sleep, doctor! She wakes up in the middle of the night several times!”

“How long has this been happening?” the doctor would say.

“I’m not sure.”

“What’s causing her to wake up in the middle of the night?” he asked still maintaining his patient demeanor.

“She complains of stomach aches every day. Sometimes she gets so sick she refuses to go to school. She will at time faint for no reason. I feel like maybe she isn’t eating enough?”

“Have you seen any other doctors?” he inquired.

“No” my father said, as he anxiously looked down at his hands as they rested on his knees.

I remember looking down at my mother who had remained still with her head down, tears now rolling down her cheeks. This tableau of my mother has forever been engraved into my memory.

She reached up for my hand and held it tight. I looked down at her and my heart broke at her expression; the conversation between my father and the doctor had made her even more upset.

“It’s all my fault!” I thought. “Why am I always causing them to worry?” the nagging voice in my head shouted as loud as it could. “It’s all MY fault! It’s all MY fault!! IT’S ALL YOUR FAULT!!”

“I’m a homeopathic doctor, Mr. Chughtai,” I heard him say as he broke the rumination of my thoughts.

“I can give your daughter a few pills, little round pills that she can put under her tongue to help, but in my opinion, I think your daughter is very sensitive. She is trying to make sense of her world, which at the moment seems to be filled with a lot of anxiety and turbulence given the state of your wife’s health. It may help to have her, as well as your other two daughters, speak to someone – a psychologist perhaps?” he suggested hesitantly.

“There’s nothing wrong with my daughter.” My father responded confidently. “She has nothing to be sad about. She just has difficulty sleeping and an upset stomach. I’m sure you have something that can help her?”

Within five minutes, my father, mother and I were thanking the doctor for his help as he walked us out of his office. My mother looked hopeless and my father seemed confused and frustrated.

“You’re probably right, Dad. I probably just don’t eat enough. I’ll start eating more and maybe try to get to bed at a reasonable time.” I blurted it out just to break the silence that plagued our once happy, versatile family. My father looked at me and smiled.

“Take the medicine…I have a feeling it will really help.” He had no doubt in his voice.

“OK…I will. I promise.”

Our journey soon came to an end as we pulled up onto our driveway. As I pulled the door of our Aerostar van open and attempted to step out, I found myself in a state of disappointment.

I knew deep down inside, that there would be no end to my racing heart, or my stomach aches. My sweaty palms, dizziness, body aches and difficult breaths, the panic and nightmares triumphed over any logic behind what I felt.

I carried my racing thoughts into the house as I turned to close the door behind me. As the door shut, I locked away any future mention of my emotional struggles by convincing myself that my parents knew best.

“There IS NO such thing as anxiety or depression and even if it were true, I would have NO reason to be depressed.”

Why?

Because my father said so.

——————————————————————————————————————

Aisha Chughtai is now 35-years-old and works as a child and youth care worker in Markham, Ontario. She lost her mother to cancer when she was 13, and just over a decade later, her father died as well. She is a strong believer that any challenge, no matter how difficult, can be overcome by taking life one breath at a time.

During the month of October, Yahoo Canada is delving into anxiety and why it’s so prevalent among Canadians. Read more content from our multi-part series here.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA andfollow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Abacus Data, a market research firm based in Ottawa, conducted a survey for Yahoo Canada to test public attitudes towards anxiety as a medical condition, including social stigmas and cultural impacts. The study was an online survey of 1,500 Canadians residents, age 18 and over, who responded between Aug. 21 to Sept. 2, 2019. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The data was weighted according to census data to ensure the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region.