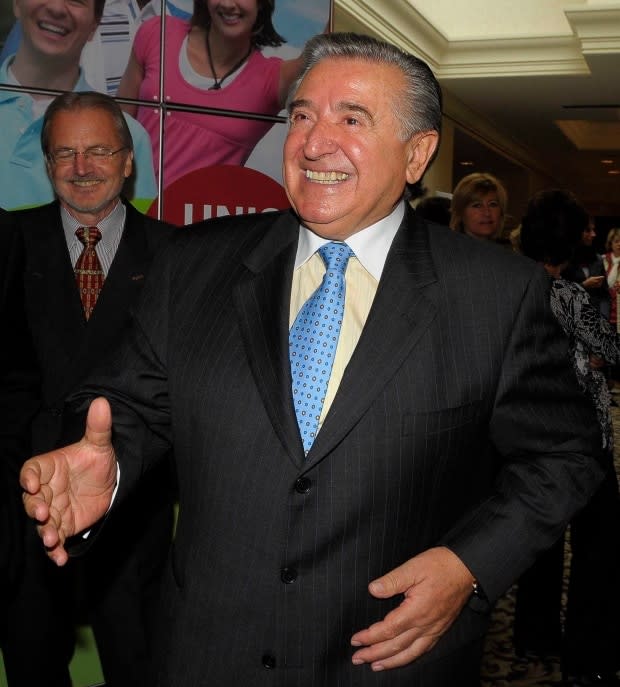

Quebec dairy mogul Lino Saputo had secret past dealings with U.S. mobster Joe Bonanno, then lied about it

Lino Saputo turned his family's humble cheesemaking business into a multibillion-dollar global dairy empire and became one of the 10 richest people in Canada in the process.

But while amassing his $6.5-billion fortune, Saputo has also been dogged by allegations of having ties to powerful Mafia figures in both Canada and the United States.

The 82-year-old businessman has repeatedly denied those allegations, most recently in a memoir published last year. He devotes an entire chapter to disputing the claims.

"We respected the law, kept our distance from criminal organizations, and avoided crossing the wrong people," Saputo writes in Entrepreneur: Living our dreams.

But between 1964 and 1979, Saputo maintained a clandestine relationship with one of the most powerful gangsters in the U.S., according to police evidence uncovered by Enquête, Radio-Canada's investigative program.

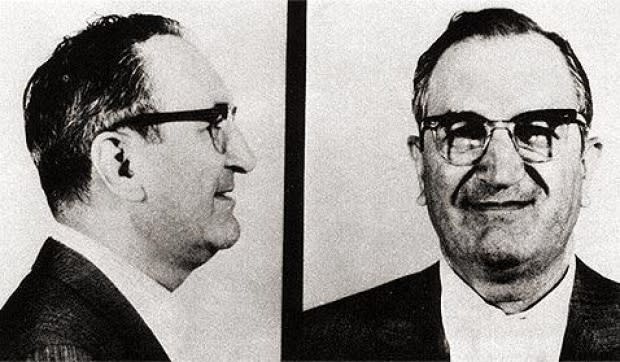

The evidence, gathered by federal and state law enforcement officials in the 1970s, details personal and financial dealings between Saputo and Joseph Bonanno, considered one of the founding members of the American Mafia.

In 1980, a retired New York judge reviewed the police evidence as part of an administrative hearing.

The former judge determined Saputo was so closely linked to Bonanno that allowing him to do business in New York was not in the public interest.

Lunch with New York godfather

Before Saputo Inc. became the dairy industry giant it is today, employing 17,000 people around the world, the family operated a cheesemaking business from a modest building in Montreal's Saint-Michel neighbourhood.

In the early 1960s, the building was also home to the Saputo family, including Lino, then in his mid-20s, and his father Giuseppe.

It was here, in May 1964, that the Saputos had lunch with Bonanno.

At the time, Bonanno was in charge of one of the so-called Five Families, the crime syndicates that composed the New York Mafia.

Bonanno says in his autobiography, A Man of Honor, that he only met with the Saputos at the insistence of a mutual friend.

However, in an immigration document that he filed during his stay in Montreal, Bonanno claimed to have known the Saputos since the early 1960s. He calls them his "friends."

The May 1964 meeting resulted in a business proposal. Giuseppe Saputo drew up a letter offering to sell Bonanno a 20 per cent stake in three companies then owned by his family, in exchange for $8,000 (around $66,000 when adjusted for inflation).

In his memoir, Lino Saputo says his family had no idea who Bonanno was when they agreed to the deal.

When Bonanno was later arrested by Montreal police for an immigration violation, Saputo saw him described as "the king of the Mafia" in a newspaper headline.

According to Saputo's account, his father "rushed" to cancel the deal.

"We thought that was the end of it, as the agreement was never finalized," Saputo wrote.

But suspicions that he had ties to the Mafia continued to follow Saputo throughout the 1970s. They were unfounded, he said, and hurt his business.

"I felt victimized and cut off from Quebec society by the false allegations based solely on our Italian origins," he wrote.

A trip to Tucson

In 1978, under the auspices of one of his companies, Lino Saputo applied for a licence to operate a cheese-manufacturing business in New York state.

State officials were reluctant to grant the application after they learned of the 1964 business deal between Saputo and Bonanno.

During the administrative hearings into his application, Saputo said under oath that the meeting in Montreal was the first and only time he had met Bonanno.

Saputo's memoir notes simply that the "judge eventually rejected our request," adding that a competitor and a Quebec agriculture official testified on his behalf.

The reason, though, was that the judge had concluded in 1980 that Saputo gave "false, misleading and deceitful statements" about his ties with Bonanno.

Radio-Canada accessed all of the evidence that U.S. law enforcement submitted to the administrative hearings into Saputo's application.

Along with testimony from U.S. law enforcement officials, the 1,500 pages of evidence detailed how Saputo disguised interactions and financial dealings with Bonanno between 1964 and 1979.

During the hearings, Saputo was asked if he had seen Bonanno after May 1964. "No, sir," Saputo replied.

He was then asked: "Were you in Tucson, Arizona, on February 1, 1970?"

Saputo answered: "Not that I remember, sir."

But FBI informants had spotted Saputo and his wife, Mirella, visiting Bonanno at his home in Tucson on that day.

An FBI agent also told the New York hearings the Saputos were checked in under the name "Saparo" at a Tucson Holiday Inn between Jan. 30 and Feb. 1, 1970.

Though Bonanno had by this time "retired" as head of the New York crime syndicate that bore his family name, authorities believed he was still active in criminal activity in Arizona and California.

Investigators in the U.S. presented no other evidence that Saputo and Bonanno had met in person after 1970.

They did, however, present evidence indicating the pair remained in contact, at least until the end of the 1970s.

Notes to 'Lino'

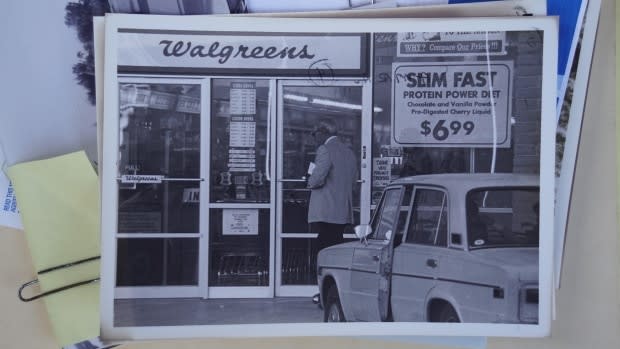

Beginning in the summer of 1975, the Arizona Drug Control District, a cross-agency task force, placed Bonanno's Tucson home under surveillance.

Twice a week, Bonanno (then in his 70s) would dutifully put his trash cans by the curb. An undercover police van would drive by the house discreetly soon after.

Officers inside the van took the contents from the bins and filled them again with fake garbage — all in less than 45 seconds. They even plied Bonanno's Doberman with meat to prevent the dog from barking.

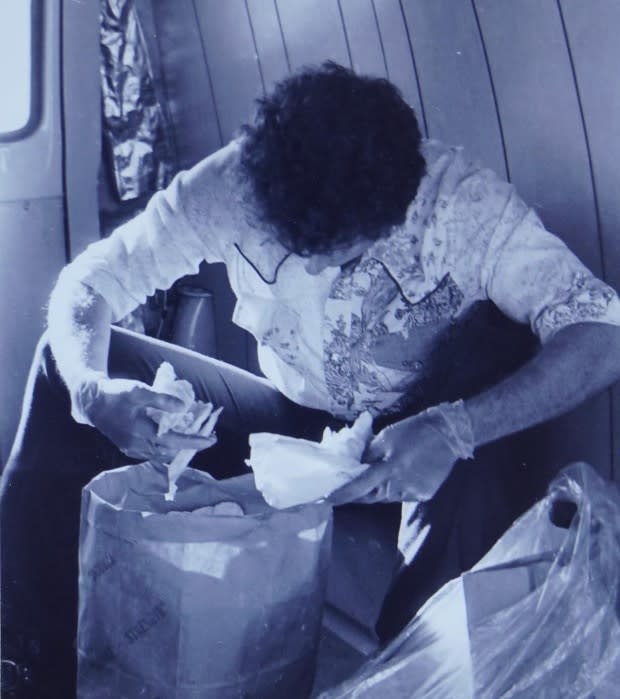

State and FBI investigators would then sift through Bonanno's garbage.

Bonanno was a diligent note-taker, tearing them up and throwing them out when he was done.

Between 1975 and 1979, police were able to piece back together around 6,000 notes and other documents from Bonanno's trash cans.

"We learned, by both studying him and watching him, that he was the most powerful Mafioso in the United States ... and had specific influence, we learned, in Canada and throughout Latin America," said Eugene Ehmann, a former investigator with the Arizona Drug Control District who played a leading role in the operation against Bonanno.

"Bonanno was still an actively known figure in New York ... He was the godfather, plain and simple."

Among the notes, investigators noticed references to "Lino." Several notes, for instance, seemed to suggest that Bonanno had helped organize a trip to California for him.

"Lino is a person of mine with no charge (1) at the hotel (2) no charge at the restaurant," reads the FBI translation of a note written in Italian.

In a recent interview with Radio-Canada, Ehmann (now retired) said that with help from the RCMP, his team determined "Lino" was Lino Saputo.

"They seemed to interact very smoothly with each other," Ehmann said of Saputo and Bonanno. "They just had a relationship, and it was a longtime one."

In 1979, authorities finally searched Bonanno's house itself. A few days later, the mobster dumped 1,200 notes in the trash, seemingly unaware he was still under surveillance.

This latest dump included newspaper articles from Quebec that discussed Bonanno and the Mafia.

Police also found lawyers' letters, financial statements and investment scenarios that linked Bonanno to Saputo and his businesses.

"[Bonanno] had obviously panicked and wanted to get rid of these documents which have — as we now have found — connected him more deeply in his relationships with Saputo Cheese," Ehmann said.

The liquido connection

The notes in Bonanno's garbage often referred to liquido, an Italian word for cash.

In several notes, Bonanno wrote that he needed to discuss liquido with someone called Peppe Freddo.

Bonanno received multiple calls from Peppe Freddo during the 1970s at telephone booths in a Tucson hospital, which were being monitored by law enforcement officials.

Ehmann said an FBI agent was occasionally lying on a stretcher nearby, trying to understand what was being discussed.

With the help of the RCMP, Ehmann said, agents in the U.S. concluded that Peppe Freddo was a code name for Giuseppe Borsellino.

Borsellino had been a business partner of Saputo's since the 1960s and was an early shareholder in his cheese businesses. He is also married to Saputo's sister, Elina.

Aside from their telephone conversations in the 1970s, Borsellino also corresponded with Bonanno. In one 1975 letter found by police, Borsellino apologizes profusely for failing to call at an agreed-upon time.

In another, Bonanno tells Borsellino: "I would like, if possible, to hear the voice of your brother-in-law and speak with him."

At the cheese-licensing hearings in New York, Ehmann and his colleagues presented evidence that Saputo colluded in funnelling $51,000 US to Bonanno (worth around $210,000 US today).

The money was withdrawn from an account belonging to a business owned by Borsellino's brother and was meant to pay an outstanding bill to one of Saputo's cheese companies.

But a disused money wrapper found in Bonanno's trash, along with several recovered notes, was evidence the cash wound up instead at Bonanno's home.

'False, misleading, and deceitful'

Law enforcement authorities presented their evidence about Saputo's ties to Bonanno over the course of a 10-day administrative hearing in 1980.

A retired appeals court judge, Charles D. Breitel, was appointed to preside over the hearing. He recommended the state refuse Saputo's application for a cheese-manufacturing licence.

In his recommendation, Breitel singled out the $51,000 in cash. He considered it a fact the money went to Bonanno "with the knowledge and collusion" of Saputo.

"Joseph Bonanno has had significant economic and transactional involvement over a substantial period of years with several Canadian cheese companies owned by the members of the Saputo family and by Lino Saputo in particular," Breitel wrote in his 1980 report.

The evidence, he said, pointed to a relationship that lasted between 1964 and 1979.

Breitel added: "Lino Saputo has attempted to conceal from the Department his and his companies' involvement with Bonanno, he has failed to furnish all the material information required by the Commissioner, and has made material statements that are false, misleading, and deceitful."

Breitel's determination was confirmed on appeal.

The investigation by U.S. law enforcement into Saputo's ties with Bonanno ended with the decision to withhold the cheesemaking licence.

Bonanno died in 2002 at the age of 97. His obituaries claimed he was the model for actor Marlon Brando's character in The Godfather.

Saputo Inc. went public in 1997. The company, which has operations in Australia, Argentina, the U.S. and the U.K., is worth an estimated $15 billion.

Saputo, a member of the Order of Canada, has never been charged with a criminal offence. He declined an interview request from Radio-Canada's investigative unit.

In a letter, Saputo's lawyer said his client has "never had ties to organized crime, be it in a direct or indirect manner."

Saputo's memoir refers to the "nightmare" of "false allegations" about being tied to the Mafia.

There is no mention in Saputo's book to Borsellino's links to Bonanno.

The one reference to Borsellino reads: "We also founded Petra, our real estate arm, now one of the largest private real estate companies in Québec, with over 8.3 million square feet of property in Montréal. My dear friend and brother-in-law Giuseppe Borsellino is president."

Borsellino has been in contact with other Mafia figures besides Bonanno.

In 1995, Borsellino and his wife, Elina Saputo, attended a wedding anniversary party for Nicolo Rizzuto and Libertina Manno.

They can be identified in a video of the event that was given to Radio-Canada by a confidential source.

Rizzuto's son, Vito, was also present. He was widely considered at the time to be the head of the Montreal Mafia.

Court documents have identified both Rizzutos as members of the Bonanno crime family.

A confidential police document obtained by Radio-Canada alleges Borsellino had contact with the Rizzutos at least until the mid-2000s.

Like Saputo, Borsellino has never been charged with a crime. He, too, declined to answer questions from Radio-Canada.

His lawyer said in a letter that Borsellino, who remains chair of Groupe Petra's board, had done "nothing wrong."

Radio-Canada asked Saputo to comment on his brother-in-law's contact with the Rizzutos. He did not respond.

Reporting by Gaétan Pouliot and Marie-Maude Denis. The English version of this story was written by Jonathan Montpetit.

If you have information you'd like to share with the Radio-Canada's Enquête team, you can reach Gaétan Pouliot at gaetan.pouliot@cbc.ca.