What It Really Takes to Be the Mayor of New York City

This article appears in the December 2020/January 2021 issue, which went to print before David Dinkins's death on November 23, 2020. The former mayor was 93 years old.

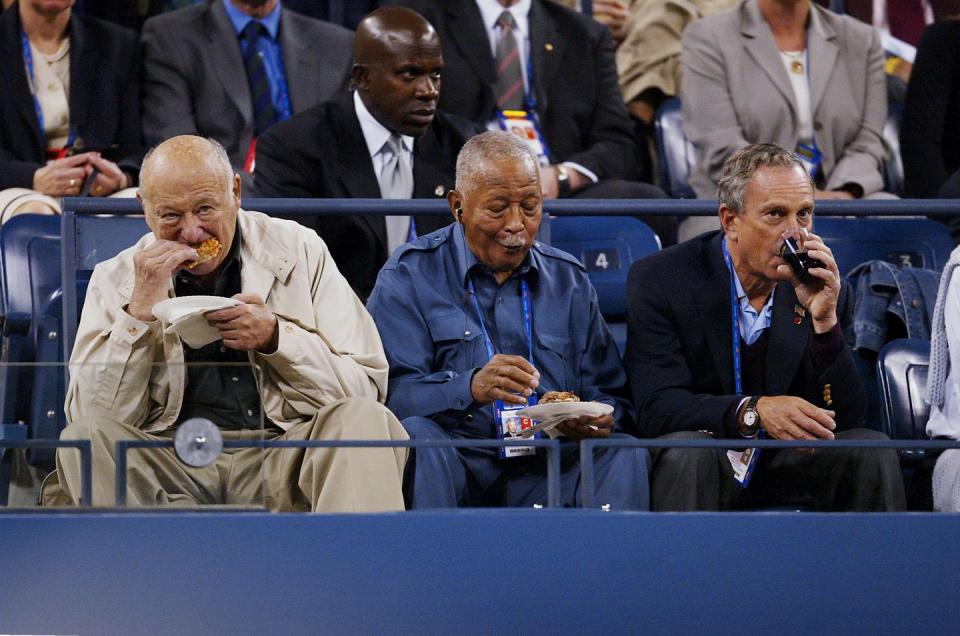

Michael Bloomberg was the current mayor. He was also one of the richest people on the planet, worth $12 billion. But it was Ed Koch who owned the room.

This was in 2008, and the occupants of City Hall, current and former, were sitting in the building’s ornate ceremonial office. Koch hadn’t been mayor since 1989. Didn’t matter. The force of his personality—by turns hammy, angry, playful, contentious—dominated the conversation. “The key was, get people to follow you,” Koch said, explaining how he had used showmanship strategically during one of the city’s darkest stretches. “I used to say—to crowds, because I went out in the streets a lot—‘If you follow me, I will lead you across the desert!’ That’s a nutty thing. But they followed me!”

Bloomberg smiled as if he were listening to an eccentric, beloved uncle. “People want a genuineness,” he said quietly. “I think it’s useful, also, to be a character. Ed was better at that than I am.”

No matter how much times have changed in New York, one thing has remained constant: The mayor is the star of our urban melodrama. We—and the rest of the country, for that matter—learned long ago to tune in and watch the show, for amusement but also because our local issues—and politicians—have a way of turning up on the national stage. The power and the enormous media platform that come with the job have long attracted egomaniacal contenders (Norman Mailer in 1969, Ronald Lauder in 1989, Jimmy “The Rent Is Too Damn High” McMillan in 2005 and two other times), plus ambitious politicians who see Gracie Mansion as a stepping-stone to the White House. The city’s current mayor, Bill de Blasio, is an excellent and painful example of that delusion: events, and New Yorkers, inevitably pull those mayors back down to earth.

Hizzoner commands a larger share of psychic space in New York than in any other major city. Partly that’s because of the extraordinary institutional resources that come with the job. Part of it is that the mayor is the only meaningful public official who is elected citywide—and in a city so big, so diverse, and so fractious, we obsess over the mayor because he unifies us, whether it’s in loving or hating him.

“People require tangible representation, but also emotional representation, the idea that the person in charge is looking out for them and what is important to them, in concept as well as in deed,” says Chris McNickle, author of To Be Mayor of New York. “You’ve got the single most important elected figure in the most important city, in the most important nation in the world. Also, New York remains the most diverse city in the United States, and probably the world. So you have a mayor who has to embody all of that—to become the human place where New York’s impossible diversity comes together in a single person.”

Bill Cunningham, who was a top city hall strategist for Bloomberg, puts it a little more colloquially: “Because the mayor represents the whole city, he becomes sort of Father Knickerbocker.” Unlike any other parental figure, however, New York’s mayor is on the receiving end of love and abuse from 8 million children. We expect him (and so far it has always been a him) to not simply manage the government but to function as the city’s id, expressing our rage or joy, and as the city’s tone-setter-in-chief, whipping us into line or rallying us, as necessary.

The first mayor to understand that his personality could be a key asset was Fiorello La Guardia, who was also the first to realize that the city’s press horde could be a helpful tool. At the time he was elected, in 1934, the unified, five-borough city was still a relatively new entity, and the biggest political problem La Guardia faced was that the corrupt bosses of Tammany Hall were still major players in city government. To wrest control, La Guardia staged pioneering photo ops—appearing at the scene of fires, smashing slot machines with a sledgehammer. He read the comics over the radio during a newspaper strike. La Guardia’s flair made him wildly popular with the public, and he converted that mass appeal into political capital.

New York’s mayors have been operating in the Little Flower’s shadow ever since. In 1966 John Lindsay—young, good-looking, patrician—leaned into the media’s Kennedy comparisons. When the city erupted in riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Lindsay walked the streets of Harlem, expressing his sympathy and calming tensions, trailed by cameras. A year later Lindsay felt the downside of the city’s close personal connection with its mayor: He was pilloried for responding too slowly to a freak blizzard.

Lindsay’s successor, Abe Beame, took a lower-key approach, with even worse results. The diminutive accountant, a product of Brooklyn’s political machine, appeared overwhelmed in the mid-’70s when the nation’s economy tanked and huge deficits brought the city to the edge of bankruptcy. The crisis, and the ugly 1977 mayoral race, produced a polar opposite successor to Beame, in style even more than in substance: Koch. “What’s funny is that before he became mayor, no one considered Koch charismatic,” says George Arzt, who was a city hall reporter before becoming a top aide to Koch, who died in 2013. “He was overweight and wore corduroy suits. Privately, Koch was a somewhat shy guy. But it was almost a dual personality: He would walk out the door and reflect the energy of the crowd. He needed that, and the city needed that at the time.”

Koch was operatic. With his refrain of “How’m I doin’?”; his hosting Saturday Night Live; his appearance one morning on the Brooklyn Bridge, yelling “Walk over the bridge! We’re not going to let these bastards bring us to our knees!” to workers heading into Manhattan during the 1980 subway strike, he raised spirits even as he cut budgets, a combination that eventually rescued the city from financial collapse. Koch’s effusive love of the job—how it seemed to be the only thing in his life—earned him affection for nearly a decade. “New Yorkers, we’re needy,” says Cynthia Greer, a political science professor at Fordham University. “We’re kind of used to being number one, and being told we’re number one. Lifelong New Yorkers have a perception that this is the only city in the world. So we want to see a mayor who is committed to the job, who isn’t looking for something else to do.”

Mayors had been central to the urban melodrama before Koch, of course. Yet his outsize presence recast the mayor as an embodiment of the city for the modern media age. After 12 years of Koch’s irascible ubiquity, though, the city wanted to lower the volume and the racial tensions, so it elected David Dinkins, a soft-spoken former city clerk and its first Black mayor. Dinkins talked of the city as “a gorgeous mosaic,” which was a hopeful image, and flattering to New York’s liberal self-image. Unfortunately, crime spiked, and Dinkins’s decency came across as passivity. Another pendulum swing. Enter Rudy Giuliani, hardass.

In driving down the murder rate, Giuliani reaped the benefits of the 6,000 new police officers Dinkins had begun to hire. But Giuliani also understood and exploited something more primal: the desire, especially among city elites, for an authority figure. Giuliani was ruthless about demonstrating that he was in command and deserved credit for every decision. When police commissioner Bill Bratton showed up on too many magazine covers, Giuliani canned him. His methods were effective but polarizing, and thousands of Black New Yorkers were hassled and arrested for little reason.

“I think the way he framed the city is the way a lot of Republicans frame governance,” Greer says. “It’s fear-based: We can only be a safe city if we lock up or get rid of people who don’t look like us.” By the end of his second term, Giuliani was deeply unpopular, until the days after 9/11, when he summoned grace at a moment it was desperately needed. “It was his finest hour,” McNickle says. “Before that episode, and to an extraordinary degree since, he has demonstrated a bizarre set of authoritarian tendencies. Many people ask, ‘What happened to Rudy Giuliani?’ Meaning he used to be normal. Actually, best I can tell, he was only normal during his first term as mayor.”

The voters hired Bloomberg next, in the hope that a wealthy businessman could revive the city’s economy, but his effect on New York’s mood and mindset ended up being just as far-reaching as that of his colorful predecessors. Bloomberg projected a dispassionate confidence, emphasizing data as the basis of his decisions. The reality of his 12 years as mayor was messier, with plenty of old-fashioned political horse trading. Yet the cooler tone he set pervaded city life, setting the stage for New York’s rebirth as—in Bloomberg the upscale marketer’s words—“a luxury product.”

What happens when the mayor turns out to be smaller than life? De Blasio could have been effective, and won over New Yorkers, without being a character. But he did need to at least appear to have his heart fully in the job. Late morning gym workouts and an absurd run for the presidency in 2020 instead made him a target of chattering-class derision; fumbling the operational response to the pandemic added a tragic overlay to his next to last year in office.

Whoever wins the mayor’s race in 2021 will face gargantuan budget holes and an ongoing public health emergency. History would seem to demand a cheerleader type, but at the moment the leading Democratic candidate in a growing field is Scott Stringer, who is running on competence, not eloquence. “Maybe no one will come along with a less technocratic, more inspiring message,” McNickle says. “But people desperately want a mayor with steel in the spine and the brainpower to respond to this crisis. The city craves leadership.” That’s not asking too much of one person, is it?

This story appears in the December 2020/January 2021 issue of Town & Country.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like