What is the 'most severe' mental illness? 52 per cent of Canadians feel like they don't know enough to say

There’s far more information out there than ever these days about health and wellness. People know that exercise helps lower the risk of heart disease, for instance, and that there are some symptoms that simply can’t be ignored, such as a new or oddly-shaped mole. And yet, generally speaking, we’re far more knowledgeable about physical well-being than mental health.

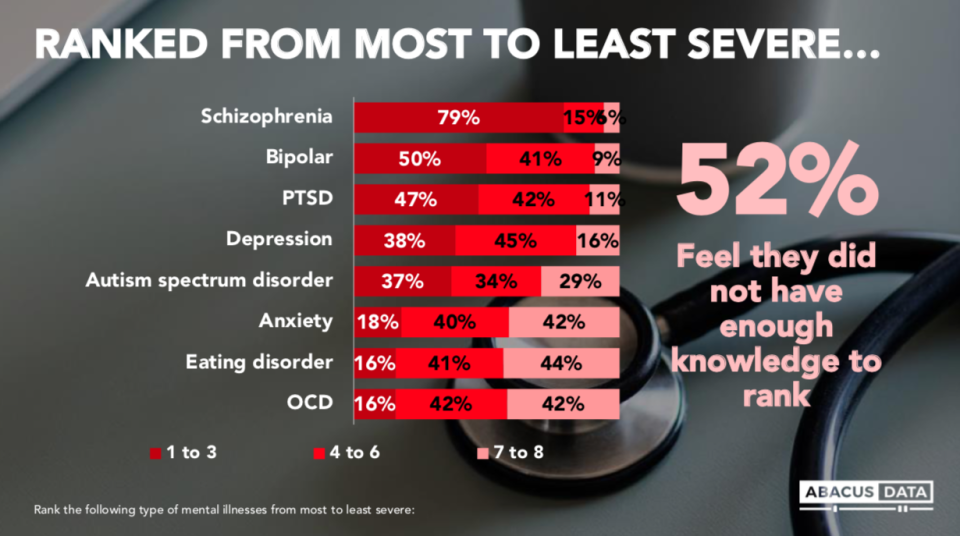

According to a new Yahoo Canada survey by Abacus Data, 52 per cent of Canadians said they did not have enough knowledge to rank mental illnesses from most to least severe.

Of those who did respond, 79 per cent ranked schizophrenia as the most serious mental illness, followed by bipolar disorder (50 per cent) and post-traumatic stress disorder (47 per cent).

At the other end of the spectrum, 16 per cent of respondents ranked obsessive-compulsive disorder and eating disorders as the most severe mental illnesses, with 18 per cent ranking anxiety as most severe.

Despite so few Canadians perceiving anxiety as a serious mental illness, the condition can seriously affect people’s daily life. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), anxiety disorders (which include subtypes, such as social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder) are the most common mental-health problem.

ALSO SEE: Nearly half of Canadians suffer from anxiety — and many believe there’s no cure

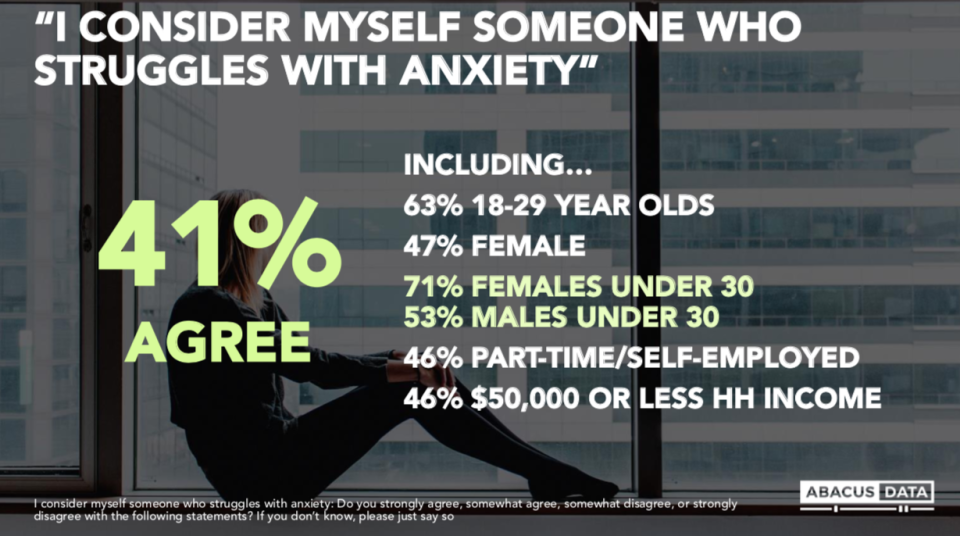

Forty-one percent of those surveyed said they consider themselves someone who struggles with anxiety, including 71 per cent of women under 30 and 53 percent of men the same age.

Symptoms of generalized anxiety include chronic, excessive and uncontrollable worry that occurs more days than not for at least six months, according to Anxiety Canada. Physical signs include muscle tension, sleep problems, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, sweating, and tightness in the chest, among many others. The feelings and symptoms can cause extreme distress and even affect a person’s ability to function effectively in day-to-day life.

“Anxiety can be very severe,” says Fardous Hosseiny, national director of research and public policy at the CMHA. “It’s alarming to us that people don’t see it as serious.”

“Anxiety responds really well to psychosocial and pharmacological and intervention; the disorders are really treatable,” Hosseiny says. “If people knew what the symptoms were, if they knew more about the mental illness and went and got services, they could get help. There’s an analogy with cancer: you don’t wait to get to stage 4 before you get treatment. With anxiety, if you don’t get help, it can get worse and worse and more severe without treatment.”

ALSO SEE: Are millennials really the anxiety generation?

Schizophrenia, ranked as the most severe mental illness by a majority of Canadians, is complex biochemical brain disorder marked by delusions (strong beliefs that aren’t true, such as possessing superpowers), hallucinations (including hearing voices), social withdrawal, and disturbed thinking, according to the CMHA. People have trouble determining what’s real and what’s not.

While schizophrenia is not curable, people can successfully manage the condition with medication, counselling, support, self-care, including the recognition of triggers and early warning signs of an episode.

Among the most severe of all mental illnesses, although not included in the survey, are personality disorders. According to a 2005 issue of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, borderline personality disorder, which is one type, presents some of the most difficult and troubling problems in all of psychiatry. About 10 per cent of patients succeed in committing suicide.

People with BPD experience instant shifts in their attitude toward people close to them, switching from idealization (love and admiration) to devaluation (anger and dislike). While people suffering from depression may endure a low mood for weeks at a time, those with BPD may experience intense bouts of anger, sadness, or anxiety that last just hours.

“The world seems to them a threatening and frightening place,” says John Livesley, emeritus/post-retirement appointee at the University of British Columbia faculty of medicine’s department of psychiatry. “As a result of this emotional instability, their relationships with other people tend to be chaotic too, and unstable. They have endless fears linked to emotionality, which adds to the instability of life.”

ALSO SEE: Is anxiety curable? Why that’s the wrong question to ask

Despite so much confusion surrounding mental illness in general, 53 percent of Canadians consider anxiety and depression to be epidemic, with that perception spiking among younger people, according to the CMHA.

Eighty five per cent of Canadians say mental health services are among the most underfunded services in our health-care system, and 86 per cent say that the Government of Canada should fund mental health at the same level as physical health.

The CMHA is calling for new legislation to address unmet mental-health needs and bring mental health care into balance with physical health care.

“By 2020, depression will be the second leading cause of disease,” Hosseiny says. “The stakes are high. We don’t want people to be suffering from mental illness when we know there’s treatment and support out there that work and that help.”

During the month of October, Yahoo Canada is delving into anxiety and why it’s so prevalent among Canadians. Read more content from our multi-part series here.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Abacus Data, a market research firm based in Ottawa, conducted a survey for Yahoo Canada to test public attitudes towards anxiety as a medical condition, including social stigmas and cultural impacts. The study was an online survey of 1,500 Canadians residents, age 18 and over, who responded between Aug. 21 to Sept. 2, 2019. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The data was weighted according to census data to ensure the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region.