Waterstones defends minimum wage in year of record profits

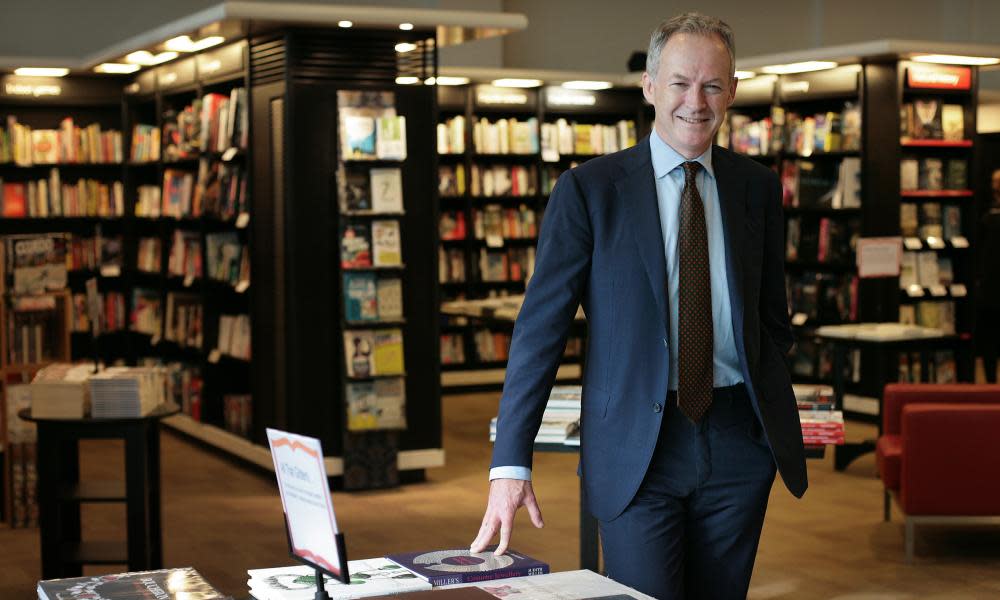

Waterstones chief executive James Daunt has hit back at campaigners who continue to call on the bookselling chain to pay all staff a living wage, saying that increasing wages for entry-level staff would be “to betray the basic principle by which we’ve been running the business”.

On Wednesday, the retailer announced booksellers’ pay would be increased in April by 6.2% across the board, almost a year after a petition signed by 9,300 writers and booksellers called on the chain to pay an hourly wage of £9, or £10.55 in Greater London. This is the amount the Living Wage Foundation (LWF) calculates is enough to live on across the UK.

The pay rise will see entry-level booksellers earn £8.21, the statutory National Living Wage. However, this remains £1.09 an hour below what LWF calculates is enough to live on across the UK, and £2.54 less than its Greater London recommended minimum.

Related: Waterstones living-wage protesters leave bookselling

In January, the chain reported its fourth straight year of rising profits: record-breaking figures for 2019 of £22.7m, up 39% from 2018.

On Thursday, Daunt defended the company’s pay policy.

“We haven’t done what would be relatively easy for us to do,” he said, “which is not pay quite so much to our managers, assistant managers, leads, experts and all of these other ranks we have, where most of our employees are employed. We haven’t taken away money from them and raised our entry-level minimum wage to the living wage. I wouldn’t get any of this grief, but that would be to betray the basic principle by which we’ve been running the business, which is that it’s our booksellers who are driving it forward. I am committed to putting as much pay as we can into those ranks.”

As part of last year’s campaign, Waterstones booksellers published anonymous accounts of their struggle to make ends meet, with some describing difficulties in paying for food and mental health problems stemming from financial stress. But Daunt said that the question of whether the National Living Wage is sufficient is “a wider debate for society and politicians”.

“It’s not that Waterstones is paying lower than all other retail jobs,” he continued. “What we do offer is that if you do stay with us – and we promote pretty quickly – the vast, vast majority of people will be promoted more or less on an annual anniversary and the best sooner than that. Obviously then you start earning more.”

Profits may be up £8.8m on last year, when Daunt estimated it would take £5m for the retailer to pay all booksellers a living wage, but with Brexit on the horizon it was foolish not to be prudent, he added: “I fear going bust in three, four years’ time because I’ve loaded up my cost base too much and that’s unsustainable.”

Last year’s profits – which Daunt put down to an exceptionally good publishing year, strong bookselling and reaping the rewards of years of work – could not be devoted entirely to pay, he said: “We have a history which shows that if you fail to invest in your business, you end up going bust.”

Daunt’s caution cut little ice with some Waterstones staff. One senior bookseller, who wished to remain anonymous, said the pay rise still left concerns over pay unanswered, because the company was only abiding by changes to the law.

“James Daunt is not doing this out of the goodness of his heart,” she said, adding that the decision to leave some staff on the National Living Wage sent a message that they are “expendable … that our concerns don’t matter. That James Daunt is more concerned with lining the pockets of his shareholders than he is with investing in the talent and wellbeing of his staff.”

Being paid the LWF’s living wage would change life drastically, she added: “I would be able to afford to leave home and actually live a life without scrimping and saving. It would ease my financial worries and mean I can have a life actually resembling one worth living.”