Why Baijiu, China's Heritage Liquor, Is Due for Its Time in the Spotlight

Ming River

In Sha He, a densely populated slice of Chengdu, the narrow streets are lined with teahouses, restaurants, and diners seated around rickety bamboo tables playing mahjong, gossiping, and drinking baijiu. I’m at Dong Zi Kou, a chipped-countertops-but-clean-plates sort of eatery whose name literally translates to “hole in the wall.” There’s a mad dash for the old-school specialties, like spicy mung bean noodles and stir-fried intestines, and the place is packed to the gills at 1 p.m. on a Friday.

“It’s normally even busier,” says Anita Lai, a native of the city and co-founder of Chengdu Food Tours, who is showing me around town. We grab the day’s specials from chefs whipping out fresh platters as fast as customers can seize them, and find a spot for ourselves on stools on the sidewalk with everyone else. Our plates are piled high with Sichuanese classics: gan yao fo chao zi, kidney slices velveted to tenderness and quickly stir fried; and suan ni bai rou, translucent shavings of cold pork belly mixed with chili oil and topped with scallions like a salad—and we wash it all down with baijiu.

Baijiu is a clear grain alcohol known for its high alcohol content, typically coming in at 40% to 60% alcohol by volume. It can be traced back nearly a thousand years to the Ming dynasty, and is made with a dried fermentation starter called qū. Like whiskey, there are as many types of baijiu as there are production techniques, regionalities, and styles. Today, most baijiu is distilled from sorghum, but wheat, rice, corn, and millet can also be used. It’s also one of the most commercially valuable liquors in the world: In 2023, around $167 billion worth of baijiu was sold in China alone. Compare that to whiskey in the United States, where revenue totaled $19 billion in the same year.

Sichuan alone produces half of all the baijiu in China, and the metaphorical buckle of the “baijiu belt” is its capital Chengdu. There are four main categories of baijiu, each one a world of nuance unto itself: Nong Xiang (“strong aroma,” spicy and fruity); Qing Xiang (“light aroma,” sweet and floral); Mi Xiang (“rice aroma,” light and floral); and Jiang Xiang (“sauce aroma,” funky and sharp with the umami of soy sauce).

“Sichuan is more known for strong aroma liquor; it pairs well with our spicy food,” Lai tells me as we eat our lunch. It’s ideal drinking food, she says: “We call it ‘fei er bu ni,’ or ‘richly fat without being greasy.’” Indeed, the dishes pair perfectly with the alcohol; the peppercorns and bright chilis are sharp, clarifying shots to the head. I gamely chase each bite with a sip of baijiu.

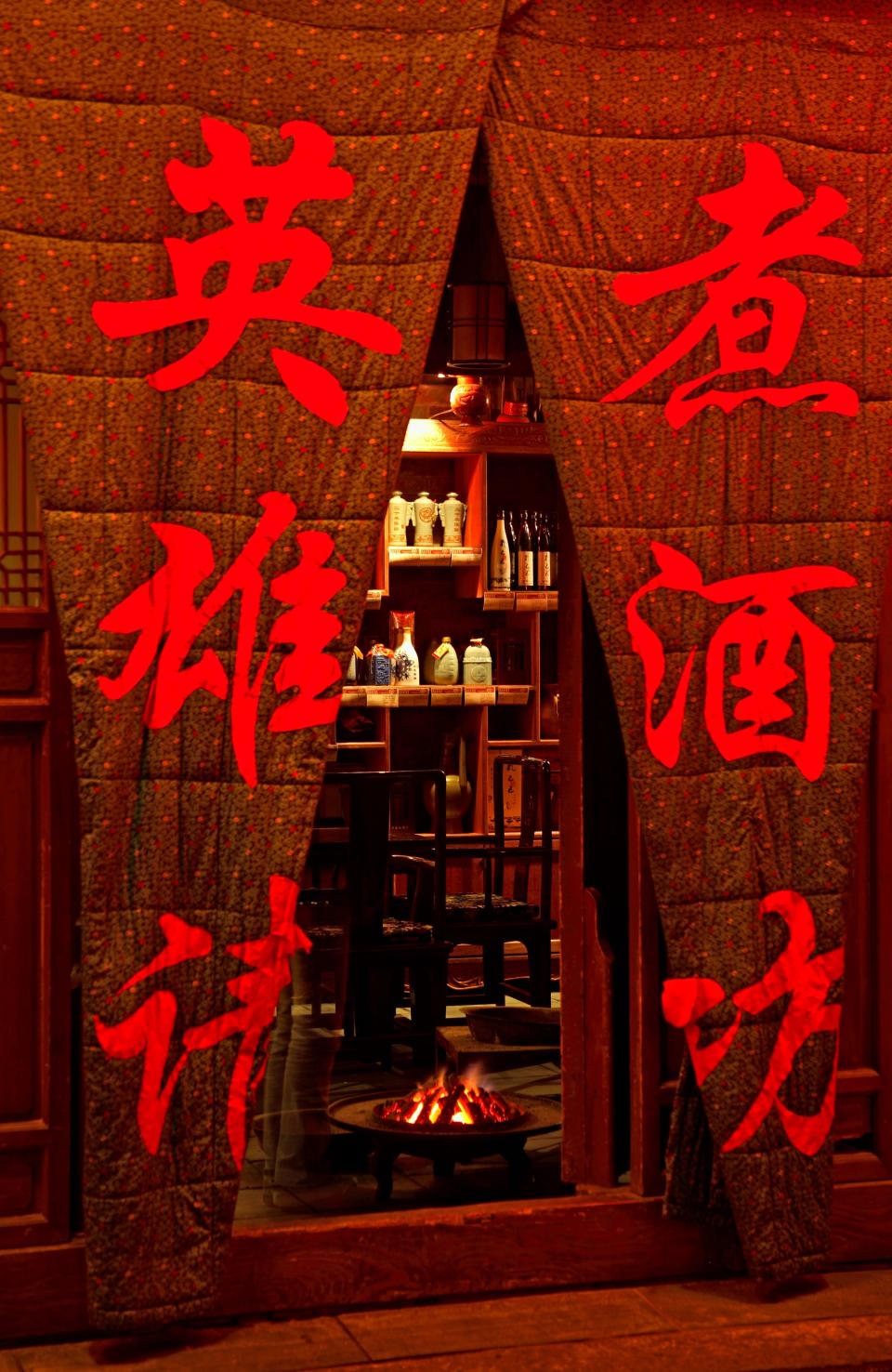

Bar at the walking street in Chengdu,Sichuan,China. Image shot 2008. Exact date unknown.

Ever since UNESCO designated Chengdu a City of Gastronomy in 2011, the world has perhaps grown more familiar with Sichuan’s spicy culinary fare than its signature spirit. (Remember when everyone was talking about Sichuan peppercorns?) But baijiu is due its time in the spotlight too, if only because drinking is so essential to life in Chengdu. At Dong Zi Ku, most tables bear bottles of clear liquor and beer tumblers the size of a small child. Once, at breakfast, I sat near an old man sipping a shot with his morning noodles. At lunchtime, I’ve seen middle-aged women buy bottles of spirits infused with medicinal herbs or fruit to share with friends. At night, along Qintai Road, I often walk past people gathering after work around bubbling hotpots, families toasting to being together. As I ate with my own family at a banquet hall in ritzy Jinjiang, I watched businessmen ply each other with expensive bottles of baijiu.

In spite of—or maybe because of—this ubiquity, baijiu is still considered an older generation’s drink, heavily associated with family dinners and business deals. Some brands depend heavily on executives and their expense accounts to purchase their top-shelf bottles. Famous ones like Maotai, which skyrocketed to prominence in the 1970s when it was served at welcoming banquets for Presidents Nixon and Reagan, start at 3,000 Chinese yuan a bottle (about $400); that’s nearly a month’s salary for many Chengdu workers. Outside of restaurants, it’s mostly older folks who buy baijiu at shops and drink it at home. They go to local merchants and tap huge clay vats by the liter; some bring their own fruits and herbs to make custom infusions. Prices at these places start at the far, opposite end of the spectrum: from around 48 Chinese yuan (about $6.60) per liter to the 300s (between $40 to $55).

On top of that, maybe baijiu has yet to make global waves outside of China because its consumption is so common that it might seem too quotidian to be interesting, or even invisible to the untrained eye. While exploring the district of Qingyang (best known for the Qing Yang Gong, a landmark Taoist temple), I stop at a wine merchant’s, unmarked on Baidu Maps, and meet the shopkeeper, who tells me that many small distilleries, like the one her family runs, are located on the outskirts of town and supply only to local stores. These spots are known only by the family’s name and a discreet sign proclaiming their wares, she explained; wander around any older neighborhood, ask around a bit, and you’ll find one.

CHINA-DRINK-BEVERAGE-TRADE-BAIJIU-CULTURE

As we chat about distilleries and baijiu distribution, I learn more about the distilleries of all sizes that are deeply embedded in Chengdu, from the family-run outfits that have been around for generations to the nationally known brands like Luzhou Lao Jiao and Shui Jing Feng, the latter of which is open for tours to visitors. Before I leave, the shopkeeper offers me a taste test and ladles for me thimblefuls of baijiu. The second-cheapest sears my throat; the most expensive one cools me down with the fruity chill of peppercorns. I buy half a liter of a middle-grade baijiu (cost: roughly $8.80) to take home in a recycled plastic water bottle.

This isn’t to say that baijiu is firmly stuck in the past. In the face of declining (though still gargantuan) sales, both older brands like Luzhou Lao Jiao and newer labels like Jiang Xiao Bai are starting pursue a younger generation of drinkers—both at home in China and abroad—with more modern-looking bottles, product placement in movies, and celebrity collaborations. Despite these efforts, every bartender I meet in Chengdu tells me the same thing: Baijiu isn’t cool with young people, who mostly drink beer or foreign spirits like whiskey and gin. They hypothesize that baijiu will find a newer, younger local audience after it takes hold on the other side of the world.

Production of Shuijingfang Baijiu, the 1,000-Year-Old Chinese Liquor that Wants to Be the New Tequila

And that’s exactly the order of business at Ming River Sichuan Baijiu, a West-facing partner of Luzhou Lao Jiao established in 2018. Ming River is courting global audiences by directly approaching bartenders, restaurateurs, and customers themselves to curating experiences that put baijiu in different a light; for example, Ming River partners with Chop Suey Club in New York for their Lunar New Year parties. Ming River’s founder, Derek Sandhaus, says the goal is to separate baijiu from the stereotype that it is “something forced down throats at business meetings or weddings. We don’t have to tell people that baijiu can be a fun experience. They can see it for themselves.”

Sandhaus, who is also the author of Baijiu: The Essential Guide to Chinese Spirits, agrees that the key to baijiu’s evolution at home in China lies with changing its image abroad: “The people who can afford fancy cocktails in China are upwardly mobile and often educated overseas. If they see it in bars while they’re studying abroad, they’ll think ‘Oh, this is an ingredient that belongs in a cocktail bar.’” Those effects may ripple out sooner than later; on recent trips abroad, Sandhaus has seen baijiu incorporated into cocktails served in New York City.

It’s a plausible strategy, but not everyone in Chengdu sees it as a sure bet. Derek Wang, owner of the mixology-focused Bar Lotus in the city’s Jinjiang district, says, “Compared to Western liquors, baijiu just isn’t ‘cool enough’ to order at a cocktail bar—not yet.” Wang has faith, however, that China’s younger generations will eventually see baijiu as something more than simply what their parents drink; Bar Lotus has tested the waters with a cocktail on a recent menu (to be rotated out for the season), creatively made of sauvignon blanc, corn juice, green bean ice cream, and Tang Bai baijiu.

In the cocktail and drinks world, ingredients have well-defined paths to widespread ubiquity, according to Wang: Think of agave spirits and margaritas; aperitifs and spritzes. But there’s not yet a standard cocktail for baijiu. “For some bartenders who like serving crowd-pleasers, that can be a little scary,” Wang says. “But for for people who are out there experimenting and coming up with new things, baijiu a really exciting category. There’s no rule book.”

But until the cocktails-du-jour the world over feature it, there’s baijiu accompanied with food that’s richly fat without being greasy, even at one in the afternoon in Chengdu, sipped with everyone else in a hole in the wall in Sha He. As lunch wears on at Dong Zi Kou, a cool breeze blows from off the river, clearing the air, just as a sip of baijiu clears my palate, leaving me ready for more.

Originally Appeared on Condé Nast Traveler

The Latest Travel News and Advice

Want to be the first to know? Sign up to our newsletters for travel inspiration and tips

These Are the World's Most Powerful Passports in 2024

The Oldest Country in the World Is This Microstate Tucked Inside Italy

This Rural Region in Spain is Paying Remote Workers $16,000 To Move There