Why Are Rich People So Easily Fooled?

We're in an anti-elite moment. The country, if not the world, has turned against "the establishment," that all-powerful thing no one seems able to define, which makes it an apt time to restage John Guare's classic skewering of the rich, Six Degrees of Separation. This April the play, which won a Tony in 1991 and ran for nearly 500 performances, returns to Broadway (at the Barrymore Theatre) for the first time since its debut. Guare's portrayal of the one percent as out of touch, securely cocooned inside their Fifth Avenue aeries (so much so that they become undone by contact with an actual member of the underclass), will strike a 2017 chord. But as the play shows, that world can be penetrated all too easily.

Like any good con man, Paul, the young African-American hustler who upends the lives of Ouisa and Flan Kittredge, a wealthy white couple, plays on his marks' vulnerabilities-mostly their vanity. Ouisa and Flan have recently become empty-nesters, left alone by their children ("two at Harvard, one at Groton," as Flan incessantly tells us) to look down on Central Park from their Kandinsky- and Chippendale-filled apartment.

Along comes Paul (based on David Hampton, a real-life grifter who conned several prominent New Yorkers), who appears at the Kittredge home in a blood-stained Brooks Brothers shirt claiming to be the victim of a mugging in which his Harvard thesis on The Catcher in the Rye was stolen. As if his deft signaling ("After the muggers left, I looked up and saw these Fifth Avenue apartments. Mrs. Onassis lives there. I know the Babcocks live over there") weren't enough, Paul puts the couple further at ease by claiming to be the son of Sidney Poitier.

As he moves into the Kittredges' rarefied world and on to other marks, he continues to capitalize on some combination of these elements-sympathy, white guilt, and people's basic trust of those who check their tacit societal boxes-in his ever more devastating manipulations. In the process Paul literally ruins lives.

And yet he's presented as complex, more than just a ruthless sociopath, as self-destructive as he is parasitic. Like his marks, Paul is seduced-in his case, by the trappings of wealth and privilege. As much as the play is, ultimately, a tragedy, like all cons this one involves an element of win-win. Ouisa (played by Allison Janney in the upcoming revival) expresses the ambiguities of the situation:

"I read somewhere that everybody on this planet is separated by only six other people. Six degrees of separation. Between us and everybody else on this planet. The president of the United States. A gondolier in Venice. Fill in the names. I find that A) tremendously comforting that we're so close and B) like Chinese water torture that we're so close. Because you have to find the right six people to make the connection. It's not just big names. It's anyone. A native in a rain forest. A Tierra del Fuegan. An Eskimo. I am bound to everyone on this planet by a trail of six people. It's a profound thought. How Paul found us. How to find the man whose son he pretends to be. Or perhaps is his son, although I doubt it. How every person is a new door, opening up into other worlds. Six degrees of separation between me and everyone else on this planet. But to find the right six people."

Like Guare's characters, we as a society seem to have a love-hate relationship with the figure who observes, who infiltrates, who exploits. We may be appalled when contemporary tricksters like the faux-Rockefeller Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter, the fauxminority Rachel Dolezal, that Miami man who went around impersonating Johnny Depp, or any of the internet frauds we encounter daily break the rules, tacit ones or otherwise, and yet they hold an enduring fascination.

When it comes to their fictional counterparts, our fascination curdles into an uneasy empathy; we find ourselves rooting for Paul, for Jay Gatsby, even for the murderous Tom Ripley in the eponymous Patricia Highsmith novel series. "What interests me so much is not the con man but the need of the mark to be conned," Guare says. "Whether it's a psychic in Chelsea or Germany after the First World War, the quality of need is so great that the con man doesn't even need to be that good!"

What interests me so much is not the con man but the need of the mark to be conned. -John Guare

When asked on NPR's Fresh Air how the New York Times defined the word lie, the paper's executive editor, Dean Baquet, said that "lie implies intent, and long-standing intent." The same might be said of impostors. They come in different varieties, of course-grifters and false nationals and seducers and impersonators-but they all have one thing in common: They are deliberate in their deceit.

Eugenia Smith, who claimed to be Grand Duchess Anastasia and published a memoir, was almost certainly an impostor. Anna Anderson, a schizophrenic woman who also claimed to be Grand Duchess Anastasia, probably was not.

Impostors make excellent copy, a fact tabloid writers have never failed to exploit. At his or her best, a serial impostor lives out a real-life picaresque, a thrillingly disjointed string of dramatic episodes. And like Paul he's often entering social echelons most of us only dream of.

In 1870 a 14-year-old girl who called herself Cassie Chadwick was arrested by the Ontario authorities for forging checks, which she claimed were gifts from a wealthy British uncle. Twelve years later she was in Cleveland, passing herself off as a clairvoyant called Madame Lydia DeVere and running up debts all over town. By the turn of the century she had gone through three husbands and somehow become the illegitimate daughter of robber baron Andrew Carnegie. In the course of eight years she had run up $20 million in bank loans under his name.

The tale of Cassie Chadwick (real name, Elizabeth Bigley) embodies many of the characteristics of the classic impostor narrative: humble beginnings, audacity almost beyond belief, multiple identities, claims of connections to wealth and power, and an apparent disregard for all the rules of society, even as they're being exploited. It's no wonder that in the popular imagination such figures have always had folk hero status.

As one might expect, due to their tragic glamour, the dramatic and cloudy nature of their fate-as well as the general fascination with lost monarchies-the Romanovs have been popular vehicles for imposture ever since the Russian Revolution. In addition to the five recorded Anastasias, the 20th century saw six Alexeis, three Tatianas, two Marias, and a Dutch woman who claimed she was a secret fifth Romanov princess.

Even before the revolution, Russians seem to have led the pack in claims of false royalty, perhaps due to the sheer size of the Russian empire, or its relative remoteness, in a premedia age, from the rest of the scammable world. But by no means was this a monopoly, for impostors have been claiming descent from deposed monarchs and dead dynasties for as long as such things have existed, and in every corner of the world.

As for more minor nobility-assorted Mittel-European barons and dusty Scottish lairds-one doesn't even know where to begin tallying. There's a reason the monocled, impoverished aristocrat of dubious provenance was a stock character in screwball comedies, serving to prick the pretensions of gullible snobs. The motives vary-credit, status, romantic opportunism-but whether the scene is from Fawlty Towers or The Confidence Man, the impostors are accorded a certain amount of automatic respect, thanks to their titles and tuxes.

When you think about it, our long-standing affection for roguish reformed sociopaths is a little peculiar.

Some impostors are sophisticates, and they infiltrate a world they claim as their native home (see "Monte Cristo, Count of "). Others, like Huck Finn's dubious riverboat dauphin, count on the people around them to be ignorant of aristocratic mores and genealogical charts and awed by the idea of nobility. As with the military (another area rife with impostors and charlatans) and even academia, the built-in structures and rules of these milieus seem to allow a particular freedom for someone who completely disregards them.

But as a general rule, and for obvious reasons, impostors tend to move themselves (or at least their characters) up the social ladder. With the exception of the occasional royal-in-disguise (The Prince and the Pauper, Queen Christina, Coming to America) or heist movies that demand protagonists pose as…well, you name it, the point is reinvention for profit or social gain. It's the American dream, in a sense, but a shortcut version.

I've heard it said that among criminals, crimes are divided into two categories: financial and psychological. Financial scammers are of course the most straightforward sort of impostor. Fraudsters like the aforementioned Cassie Chadwick, Victor Lustig (who sold the Eiffel Tower twice), and other claimants to fortunes and unlawful gains are pretty clearly in it for the money. And yet, in the cases that capture our cultural imagination, there's more going on.

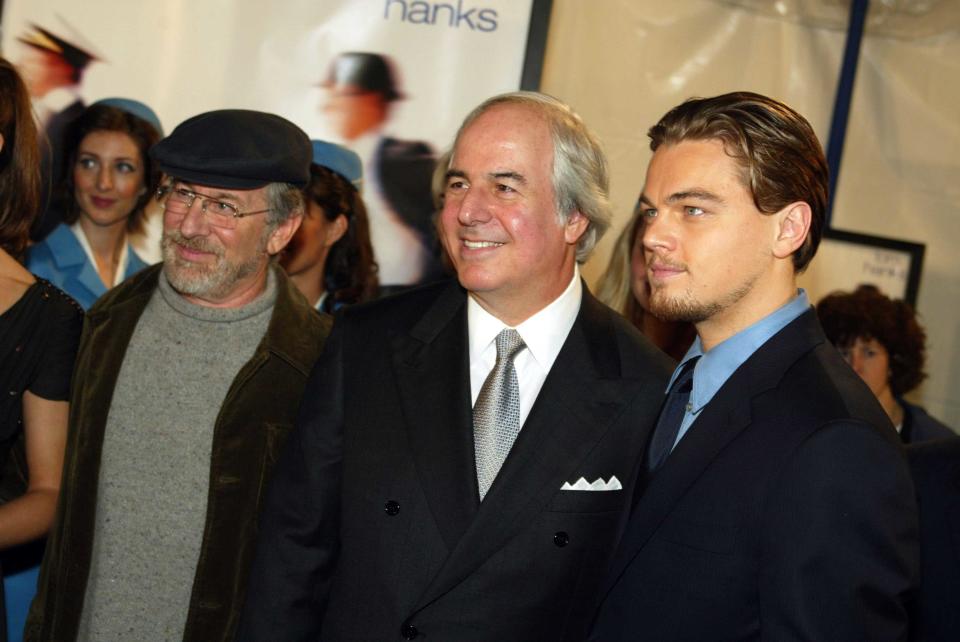

Like Six Degrees of Separation, the film Catch Me if You Can is not just the story of a young forger. Rather, it's about a man, Frank Abagnale, who felt compelled to get away with as much as the world would let him, whether that meant posing as a pilot, a college professor, a business tycoon, or a playboy. When you think about it, our affection for roguish reformed sociopaths-be it Abagnale, The Music Man's Professor Harold Hill, or Working Girl's spunky heroine, Tess-is a little peculiar.

Even in stories in which the impostor is an unmitigated psycho, such as the aforementioned Tom Ripley, something in us wants him to get away with it. We want Ripley to pass as a Princeton-educated blue-blood who knows the rules of white tie and fish forks. If he can do it, perhaps it's just that easy. Maybe it's an element of Robin Hood–style subversion; maybe it's just a deep-seated love of vicarious chaos. Or just not wanting a story to end.

And yet the idea of an old-fashioned impostor often feels confusingly seductive. When the saga unfolded of "Clark Rockefeller," a German man posing as a scion of the oil fortune who may or may not have been a murderer on the lam for decades, we were all rapt. "How could he get away with it?" we wondered, even as we consigned another e-mail from a diamond-bedecked African king to the spam folder. It's as if, in taking on these high-society identities, these avatars adopt the impunity we associate with that level of success. The rules simply don't apply.

Samuel Johnson had a terrific line on this subject, as on so many others. "It is to be feared that the science of overreaching is too closely connected with lucrative commerce," he wrote in Sermon 18. "There are classes of men who do little less than profess it, and who are scarcely ashamed, when they are detected in imposture." That, in a nutshell, is both the attraction and the repulsion of the impostor. What is shame, and what is its absence? We are all implicitly laboring for success, for glory, for material gain. What if everyone just threw off the shackles of morality and pursued these things? When others do, it is thrilling and exhilarating and profoundly scary. And the sheer energy of living a lie! It's a vocation all its own, in a way.

Imposters tend to move themselves up the social ladder. It's the American dream, but a shortcut version.

Six Degrees of Separation has not been revived since its original run, and we live in a different world now-in some ways, a world more full of impostors than ever before. Credit card fraud, catfishing, fake news stories, fake Twitter identities, and strangers pretending to be dying of lurid illnesses are daily realities. To say nothing of our politicians. We are now certainly less trusting than Flan and Ouisa.

And yet the questions the play raises-of reality, of class and racial tensions, of what it means to make it in America and what real achievement means in a world of appearances-well, they're more pressing than ever. Says Guare, "After all, how much of any relationship-how much of love-is a con game? How much of our lives is waiting for a person who says, 'I will be what you want and reflect what you want to see back at you'?"

This article originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like