How California Winemakers Changed How Wines Are Named

This story is from an installment of The Oeno Files, our weekly insider newsletter to the world of fine wine. Sign up here.

In a world where bottle shops, wine lists, and even home collections are organized by grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, and Chardonnay, it’s hard to imagine that not that long ago, no one referred to wine by its varietal moniker. Old World wines have long been called by the name of the appellation they’re from, such as Burgundy, Barolo, or Rioja. But as wine industries emerged in various parts of the New World, they wandered through an identity crisis. Instead of naming wines for the regions where they were actually grown, New World vintners simply slapped derivations of old-world appellations on their bottles. So in the U.S., wines had generic names aping some European region in an attempt to get consumers to buy them, hence “Champagne” from Sonoma County. But as California winemaking gained a foothold after Prohibition and World War II, a core group of vintners—led by one in particular—sought to carve out a more defined identity for American wine.

More from Robb Report

This $14.5 Million NorCal Abode Takes Its Design Cues From Frank Lloyd Wright

Inside a $6.4 Million Home With Exclusive Access to Malibu's Famed Paradise Cove Beach

No Joke, California Will Soon Require Your Car to Beep at You if You Speed

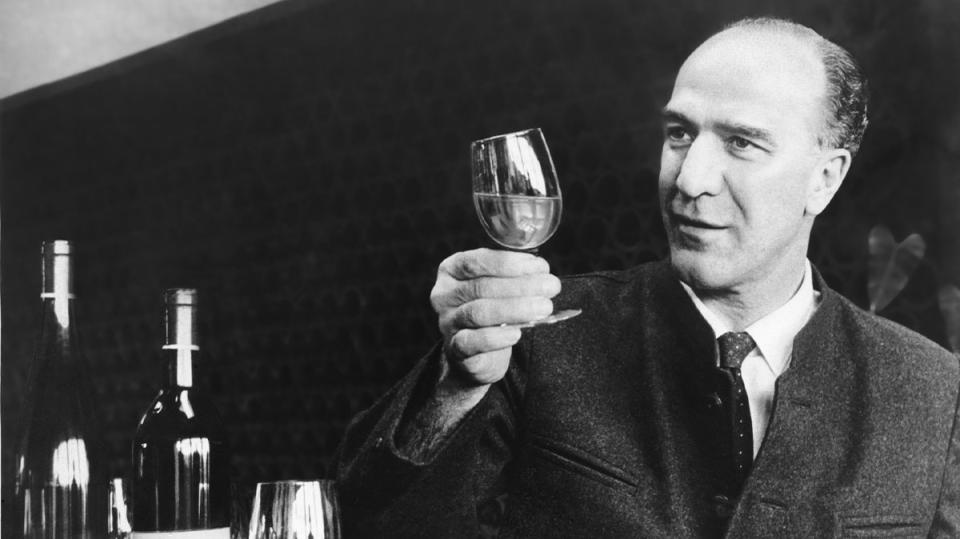

Two of the greatest forces on the way Americans eat and drink were chef Julia Child and winemaker Robert Mondavi, whose influence is chronicled in winemaker Tor Kenward’s 2022 memoir, Reflections of a Vintner. Kenward arrived in Napa Valley in 1977, and although the California wines that had stunned the world in the previous year’s Judgment of Paris were all labeled by variety—Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay—his first employer, Beringer, was still selling a red blend known as Barenblut, which is German for “bear’s blood,” and a Central Coast Riesling called Traubengold, which translates to “golden raisin” in English and appears to have been borrowed from an Austrian producer.

Kenward points out that these wines and those with names like Claret, Burgundy, and Johannisberg Riesling were still popular stateside in the 1970s. “Please remember America is not considered a wine-drinking culture; it is more puritanical, and naming wines after the proper grape variety was not the way to sell wine,” Kenward says. “More familiar or geographical names worked better.” However, before Kenward moved to Napa, the seeds had already been sown for a new approach to naming, according to Robert’s son Michael Mondavi. Amid a sea of offerings called Hearty Burgundy and Mountain Chablis, a handful of winemakers started looking for a new way to label their wines.

But what to call these bottles produced in California? The Old World had centuries of winemaking behind it so that regions had coherent styles consumers could recognize—essentially, buyers already had a good idea what Burgundy was, so there was no need to label it Pinot Noir for them. That was not the case in California, where no formal appellations even existed until 1981, when Napa Valley became an AVA. So naming wines for a defined region wouldn’t have made much sense for post-WWII vintners in California. Sure, an American winery could label itself as Burgundy if it was made with Pinot Noir, but that wouldn’t really help this nascent group establish its own identity. That’s where varietals came in.

“My father, then at Charles Krug Winery, and other original Napa Valley winery owners in the 1940s began to put Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, et cetera, on labels,” Michael says. Wineries Louis M. Martini, Inglenook, Beringer, and Beaulieu produced bottles with generic names like “Claret,” while simultaneously introducing varietal labeling. And travel writer Frank Schoonmaker, who consulted on marketing for Almaden, was also a big influence in promoting this new practice.

When Robert left Charles Krug and founded his eponymous winery, he’s believed to be the first to label the majority of his wines by grape name. The initial vintage at Robert Mondavi was 1966, and the operation behind it was pretty lean.“We had three employees: my father, myself, and Warren Winiarski working with us in the cellar,” says Michael, who was at the winery with his father through the early days. “We produced about 10 different varieties of wine in 1966, and all of them were named for the variety: Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Zinfandel, Gamay, Chardonnay, and White Riesling. We never considered producing a generic wine. Even our rosé was named Gamay rosé.”

It was at this same time that wine from California, and Napa in particular, started to become recognized for its quality throughout the United States. In the absence of a formal appellation system, varietal labeling set quality American wines apart. The 1960s became a turning point for labeling and also for the region as a whole. “It was all part of the revolution of vintners, consumers, and the international marketplace’s acceptance of California wines,” Kenward says.

Of course, it wasn’t smooth sailing from the introduction of the grape’s name on the bottle. Retail stores pushed back, and distributors weren’t that interested because they were focused more on spirits than wine. “It was really the restaurants that embraced the varietal labeling of California wines,” Michael says. A little of bit of international tension also bolstered the Mondavi case to move toward varietal naming. French regional control boards pressured the United States to stop using protected appellation names on wine, and, at first, the California Wine Institute fought the French to allow Americans to keep using Gallic regions to name their products. There are still some holdouts that were grandfathered in when international law helped to usher in sweeping change. That’s why Almaden still makes five-liter boxes of Mountain Chablis and Mountain Burgundy, both sourced from California, while Korbel continues to use the name Champagne for its Golden State sparkling wine.

But even the pioneering Mondavis had some doubts about their approach. “We were tasting the dry Sauvignon Blanc, which was what the Napa and Livermore wineries were calling it at that time, and my father was concerned that no one was interested in buying dry Sauvignon Blanc,” Michael says. So they sought out a name they thought they could market and consulted a book by wine writer Alexis Lichine, one of the few experts in the field at the time. “My father and I looked up the Loire Valley,” he explains. They both liked the idea of Pouilly-Fumé, but he points out, “We did not want to totally plagiarize the French, so we played with the wording.” They considered Blanc Sauvignon and Sauvignon-Fumé, but those names seemed a bit clumsy. But when they hit on Fumé Blanc, it stuck, and they slapped it on the label in large type with the words dry Sauvignon Blanc in smaller print just below.

Beyond just labeling, the Mondavi brand was trying to chart a new path for American wine with the juice inside, too. “In the late 1960s, Sauvignon Blanc in California was not as interesting as it is today,” says Robert Mondavi Winery’s current director of winemaking, Kurtis Ogasawara. “It was often sweet, flabby, and lacked personality.” Mondavi’s style of Sauvignon Blanc was a hit with the public, and the Fumé Blanc endures. While the winery is now owned by Constellation Brands, the label remains among its best-sellers today.

While nearly a century ago, Americans were aping the Europeans when it comes to naming, the tables have since turned. “Variety labeling has not only changed the way Americans buy and drink wine, it has changed the world,” Michael says. “France, Italy, and Spain have all modified their regulations to where they can now call their wines by the varietal name. For years in France, they could not use varietal names.” For example, until quite recently the words “Pinot Noir” and “Chardonnay” could not legally appear on wines from Burgundy, while today they are permitted on entry level bottles of Bourgogne Rouge and Blanc. Michael imagines that “90 percent of American wine consumers don’t even know that many years ago most California wines were labeled generically.” But Robert and other Napa pioneers pushed so that American wine would be seen as anything but generic.

Do you want access to rare and outstanding reds from Napa Valley? Join the Robb Report 672 Wine Club today.

Best of Robb Report

Why a Heritage Turkey Is the Best Thanksgiving Bird—and How to Get One

The 10 Best Wines to Pair With Steak, From Cabernet to Malbec

Sign up for RobbReports's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.