'Things have gotten a lot more direct': Mother and daughter open up about coping with anxiety

*Editor’s Note: Sarah Rohoman is currently an editor with Yahoo Canada.

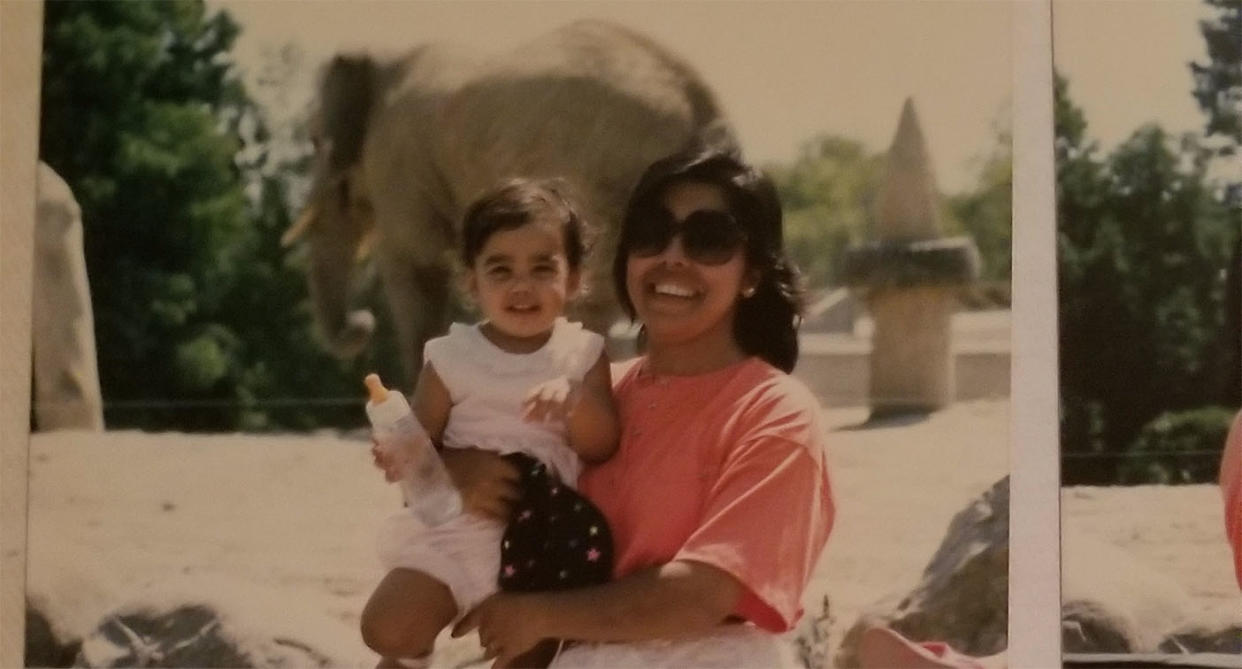

Aziza and Sarah Rohoman are a mother-daughter duo with a relationship they both describe as close and open. But since Sarah, now 28, was a child, their relationship has developed as they navigate Sarah’s anxiety.

According to Aziza, Sarah’s anxiety started when she was in grade 3. She was in a challenging gifted program in school and began to get “fake ear infections” on a regular basis. Aziza took Sarah to the doctor once or twice a week as her daughter continued to complain about the pain. A pediatrician later told Aziza and her husband that this ear pain was entirely in Sarah’s head — and was brought on through Sarah’s anxiousness at school.

“At the time, I didn’t notice,” Aziza said about this period in Sarah’s life. “Initially, I didn’t think of it as anxiety or panic attacks, I didn’t even put two and two together.”

Sarah herself recognizes that she was a nervous, high-strung, sensitive child and got very upset when she transitioned into the gifted school program, but felt everyone else in her class was the same way: high achieving children who were also nervous about it.

ALSO SEE: ‘C’mon. That stuff isn’t real’: What it’s like to suffer from dissociative panic attacks

As Sarah went into high school she, like every other high school student, found out that there were some subjects that were more difficult for her to understand than others. For Sarah it was math, and as the math work came in, her anxiety would creep up.

Sarah and Aziza both say that Sarah needed a lot of support at home to keep her anxieties at bay and push forward through her math courses.

“There was always a light at the end of the rainbow,” Aziza said.

“I think them knowing that certain things would upset me or bother me were important to me,” Sarah said.

When Sarah went away to university, that’s when she hit her low point — when she didn’t have her parents physically there to check in on her progress and how she was handling the workload.

In one particular instance, Sarah’s parents were in China, she had a bunch of deadlines on her plate and her anxiety took a more severe turn.

“I had an essay I needed to get a topic for about the Iranian revolution and I couldn’t come up with anything, I just felt so stupid and like such a failure,” Sarah said. “And I remember being in bed and thinking, ‘I cannot get out of this bed or something terrible is going to happen.’”

This is the point when Sarah went to seek mental health support on the university campus and was eventually prescribed anxiety medication for her condition, initially unknown to Aziza.

“As a parent you feel really hurt and really wish you could do so much more for your child,” Aziza said. “But I was actually proud of her, that she actually went to get help.”

To this day, Sarah still struggles with anxiety, but she has a better understanding of her needs and what’s best for her mental health.

Identifying and managing anxiety

When it comes to managing her anxiety, Sarah said her mother was “remarkably intuitive” to identify that something was wrong all those years ago.

“I don’t think I knew how to express it was a medical condition,” Sarah said.

ALSO SEE: Does no one care about anxiety? New survey results are bleak – but there’s a catch

According to a recent Abacus Data survey commissioned by Yahoo Canada, mental-health literacy and openness varies among different religious groups and cultural upbringings.

Although Aziza doesn’t associate any cultural stigma with how she understands and manages her daughter’s anxiety, Sarah did feel that her family’s Caribbean culture played a role in the way her family discussed and handled her diagnosis.

“No, not at all. I never correlate one with the other,” Aziza said.

“We don’t talk about mental illness or mental health,” Sarah said. “It wasn’t seen as a larger, systemic, lets-go-to-the-doctor problem.”

Sarah’s example of this is the way her parents were able to tackle isolated issues, like dealing with her problems in math classes, but they were less open about talking about the pressures and anxieties as larger issues.

“Doing the thing, rather than addressing the thing, which I think is largely part of the culture,” Sarah said.

But as Sarah and Aziza continue to explore the anxiety spectrum together, their knowledge, language and understanding of the condition has expanded significantly.

“Things have gotten a lot more direct as we’ve navigated the situation together,” Sarah said.

Aziza’s work to understand her daughter’s mental illness has also helped her understand her own anxieties, particularly when it comes to dealing with her mother, who has lost her mobility.

“I think when you give something words you give something power and I think being able to recognize the power that these emotions can have over your life is validating in a way, particularly when it comes to her relationship with her mother,” Sarah said.

For parents who have anxiety, Aziza’s core piece of advice is to be proactive to work towards treatment methods that work for your child.

ALSO SEE: How does anxiety manifest itself across Canada?

“You have to keep a close eye on that child and keep the lines of communication open,” Aziza said.

As Sarah continues to progress in her career, Aziza is particularly proud of the fact the her daughter has come to place where where knows how to manage her anxiety on a day-to-day basis. While she might have moments where she needs some time to herself, Sarah’s work has stimulated her in a way that has helped her to get a grasp on living her life with her anxieties.

During the month of October, Yahoo Canada is delving into anxiety and why it’s so prevalent among Canadians. Read more content from our multi-part series here.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

Abacus Data, a market research firm based in Ottawa, conducted a survey for Yahoo Canada to test public attitudes towards anxiety as a medical condition, including social stigmas and cultural impacts. The study was an online survey of 1,500 Canadians residents, age 18 and over, who responded between Aug. 21 to Sept. 2, 2019. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The data was weighted according to census data to ensure the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region.